The heat is on, as both sides urge voters to choose ‘leave’ or ‘remain’ in the run-up to the UK’s historic EU Referendum on June 23rd. New polls are coming in thick and fast, but while the outcome is uncertain, what is certain is that many voters have yet to decide. The ‘Don’t Know’ voters – around five million of them – could be crucial to the result and there’s a lot more to a ‘Don’t Know’ vote than you might expect, say Kingsley Purdam, David Bayliss, Joseph Sakshaug, and Mollie Bourne.

So you don’t know whether to vote Remain or Leave in the EU Referendum, or whether to vote at all. Maybe you’re still weighing up the evidence or perhaps your views keep changing? You are not alone!

The undecided

Opinion polls suggest that around 10% of the UK population ‘Don’t Know’ which way they will vote. Even some MPs have admitted they ‘Don’t Know’ and some have changed their mind. The Prime Minister’s commitment to Remain has also been questioned .

Although you can choose to abstain in the forthcoming referendum you cannot vote ‘Don’t Know’. Following the recommendation by the Electoral Commission we are being asked to indicate with a cross whether the UK should Remain or Leave rather than a Yes or No response. This compares to 1975 when we were asked whether the UK should stay in the European Community – Yes or No. This time you can write ‘Don’t Know’ on your ballot paper but it won’t count.

Although the word ‘Remain’ is included in the question and comes first on the ballot paper, there is potentially more scope for voters to be undecided. Research has shown that in surveys and elections, question wording and option ordering can have an impact on people’s choices.

There was disagreement amongst the government in 1973 about the decision to enter the European Economic Community but in the referendum two years later an overwhelming majority of people voted to stay in. However only 64% of the registered electorate voted. So were all those who did not vote ‘Don’t Knows’?

‘Don’t Know’ doesn’t mean don’t care

In the context of increasingly polarized political alignment in politics, including the rise of far right political parties across Europe it is important to understand the nature of a ‘Don’t Know’ response. Arguably, it is not anti-politics but anti the present form that politics is taking, that is driving the shifting alignments and levels of ambivalence.

Answering questions involves complex cognitive tasks including understanding the question, retrieval of relevant information from memory, integration of the retrieved information and articulating an answer. The inability or reluctance to carry out some or all of these tasks may give way to a suboptimal response. A ‘Don’t Know’ response can be driven by what is termed satisficing – where respondents take cognitive short cuts – in a number of ways including: being indifferent and not having an opinion either way, having a conflicted attitude, being uncertain due to not having the knowledge and having a directional view but not wanting to express it.

Looking at survey data from across Europe, we can see from interviewer assessment data that people answer ‘Don’t Know’ in response to factual, value and attitudinal questions and the level of ‘Don’t Know’ responses can vary across different populations. Substantial numbers of respondents can be reluctant to answer and seek clarification and help from others before answering, even though this might affect the standardization of the interview.

Research has shown how the selection of so-called ‘non opinion’ options can vary by level of education, even when respondents are given all the information needed to answer a question. Research has also shown how removing ‘Don’t Know’ options can encourage some respondents to provide directional responses consistent with their views expressed in later answers.

Will people who ‘Don’t Know’ determine the outcome?

If we look back to a pre-referendum survey conducted two weeks before polling day in 1975, 15% of people had not decided how they were going to vote. Women compared to men were more likely to be undecided. Data from the follow-up survey three weeks after the vote suggested people were still unsure about how they had voted. Only 42% of people felt they were ‘very sure’ they had voted the ‘right way’ and 10% of people were ‘not very sure’. Women compared to men were more likely to state that they were ‘not very sure’ they had voted the ‘right way’. So even after voting, people can still be unsure.

The ‘Don’t Knows’ and how they vote are potentially going to determine the outcome of the 2016 Referendum. In a recent poll of polls around 14% of people stated that they ‘Don’t Know’ how they were going to vote with Remain having only a small lead over Leave. As the day of the referendum draws closer some polls are showing a lead for Leave.

The percentage of people who state that they ‘Don’t Know’ how they will vote is decreasing, however few polls have reported that it is less than 10%. This could equate to five million potential voters.

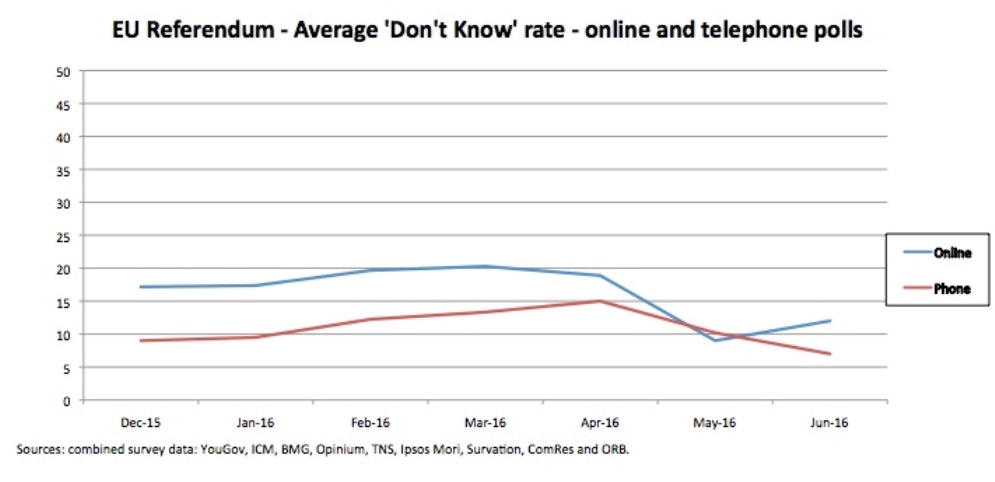

The EU Referendum – ‘Don’t Knows’ 2015-2016

The differences in the level of ‘Don’t Knows’ between on-line and phone polls is thought to be linked to variations in question wording, interviewer prompting and also sampling. Of course given the shortcomings in the accuracy of the polling at the last UK general election it is important to treat any poll with caution.

Last minute decision?

Some people may have always been ‘Don’t Know’ and some people may be changing their mind. A recent You-Gov survey, which included a follow-up question to people who indicated that they ‘Don’t Know’ how they will vote, found that around half still stated that they ‘Don’t Know’.

Communicating to the public can be a challenge. In the 1975 Referendum follow-up survey, only 43% of people stated they had read the government leaflet about the referendum. Ahead of the 2016 EU Referendum, the competing evidence claims by the different political campaigns have no doubt added to some people’s sense of not knowing which way to vote. The fact checking organization Full Fact has highlighted some of the questionable claims on both sides of the campaign as has the BBC.

We can also learn from 1975 in terms of how far ahead of polling day people made up their mind. In 1975 the post referendum survey suggests that only just over a third of people had made up their mind a ‘long time before’ polling day, while 23% of people decided ‘just before’ polling day. Women were more likely than men to have made up their mind at the last minute.

The ‘Don’t Knows’ are likely to be a major factor in the outcome of the EU Referendum. Many people are still making up their mind which way to vote. As with any decision it is important to weigh up the evidence. Information to inform your thinking is out there, if you can find it! History suggests that many people who cast their vote may still have doubts after the referendum.

The final decisions of the ‘Don’t Knows’ may be the ones that determine our future.

- This blog post is part of ongoing research at the University of Manchester into not knowing and political decision-making. For more information contact Dr. K. Purdam.