The gender pay gap is considered a key indicator of gender equality as a whole. Here, Professor Jill Rubery breaks down the data behind local and national pay disparity, and offers policy based solutions which positively affect both male and female workers.

- The narrower gender pay gap in Greater Manchester, compared to England as a whole, is not due to higher pay for women, but instead to lower relative pay for men.

- Since 2010, there has been a decline in both job opportunities and pay in the public sector, with particularly negative consequences for women who make up most of the workforce.

- Public sector pay and conditions are primarily set at national level, but more can be done at local or regional level to improve conditions for workers in outsourced services through commissioning policies.

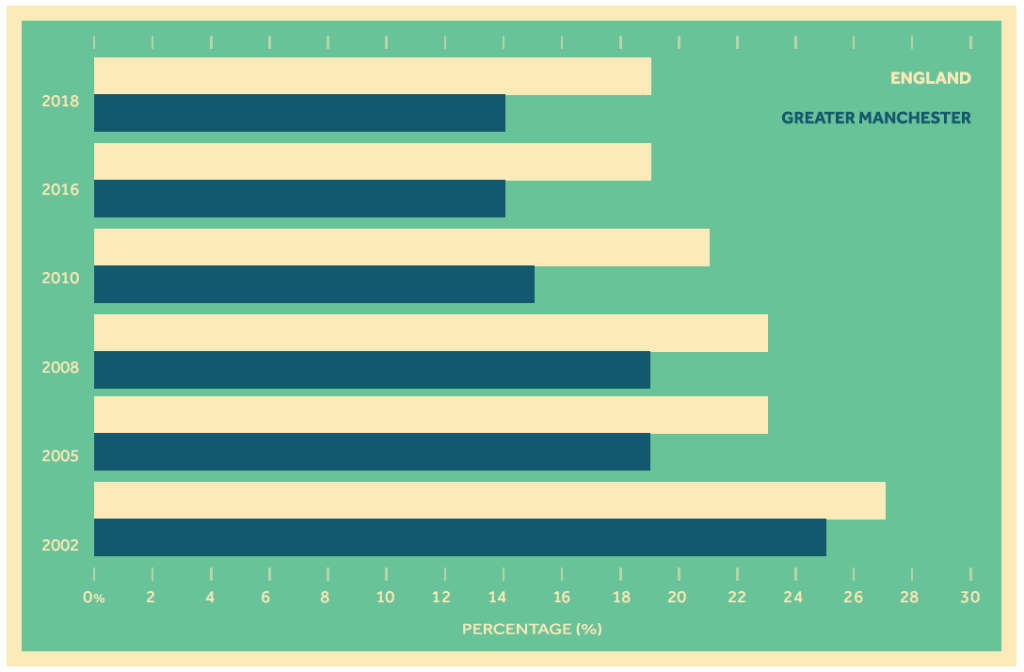

A key indicator for gender equality is the gender pay gap. At first glance, the data appear to provide good news for Greater Manchester: the gender pay gap is below that found for England as a whole. The gap in median earnings for all employees of working age is 14%, 5 percentage points below that for England at 19%. In 2002, the gender pay gaps for Greater Manchester and England were only different by two percentage points, but the gap has subsequently widened, reaching 6 percentage points in 2010. The narrower gap in Greater Manchester compared to England as a whole is not, however, due to higher pay for women, but instead to lower relative pay for men. Women’s median pay in Greater Manchester is approximately 5% less than the median for England but men’s median pay in Greater Manchester is approximately 10% below that for England.

The consequence of men faring worse in Greater Manchester is that women’s earnings are likely to contribute more to family and household income in Greater Manchester than for the country as a whole. The gender pay gap is also an average measure and does not tell us much about what is happening for groups of women at different ages, with different skills, living in different locations.

To explore these issues further, we look at what is happening at both the bottom and top ends of the labour market and how this may be impacting on gender pay gaps and overall gender pay equality.

Figure 1. Gender pay gap for Greater Manchester and England 2002-2018. Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) (accessed via Nomis) – median hourly pay excluding overtime (author’s own calculations)

Risk of low pay

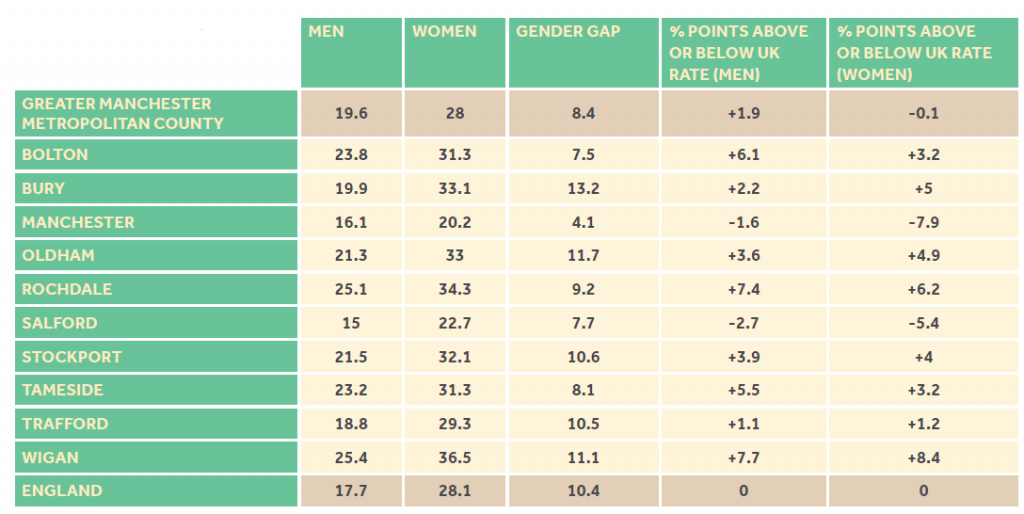

When we look at the risk of receiving low pay, we find that the share of men in Greater Manchester being paid on adult rates below the voluntary living wage is 19.6% – 1.9 percentage points above the share for men in England at 17.7%. For women in Greater Manchester, the share is 8.4 percentage points higher than for men at 28%. This is in fact almost the same – just 0.1 percentage points below the average for women in England. The gender gap in shares earning below the voluntary living wage is in fact two percentage points higher in England than in Greater Manchester at 10.4 percentage points.

This apparently positive picture for women is not found in all areas in Greater Manchester when we look at the data by local authority. Manchester and Stockport record lower risks of low pay for both sexes than the average risk for England, but all eight other areas record higher risks. Rochdale and Wigan have the worst records for both sexes, accounting for over a quarter of all men’s jobs and over a third of women’s. The gender gap in risk of being paid below the voluntary living wage is also above the national average in five of the ten local authority areas. What we find then is that although women are still bearing on average by far the higher risk, place of residence is also a major factor. In fact, the share of men being paid below the living wage in Rochdale and Wigan exceeds the share of women in Manchester and Salford.

Figure 2. Share of men and women paid below the voluntary living wage set by the Living Wage Foundation (% on adult pay rates). Source: ASHE analysis 009211

Opportunities for higher pay

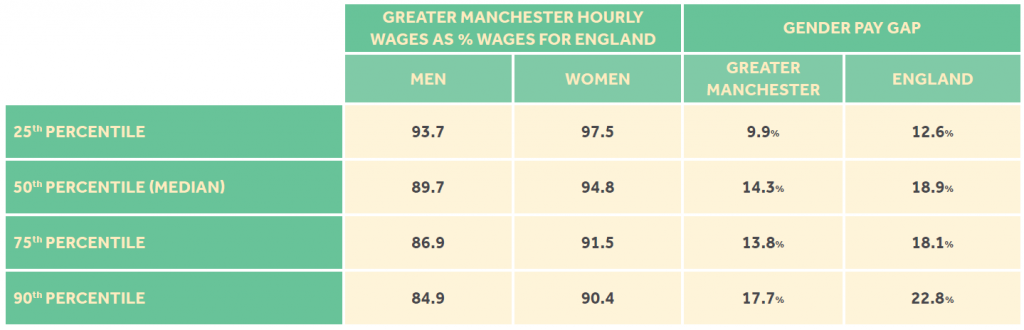

So far we have been looking at the gender pay gaps for both low paid and median workers, but gender equality also depends on access to higher paid jobs. In much of the reporting on the gender pay gap, it is inequalities in access to higher ranks within companies that has attracted media attention. We do not have the data for investigating that here, but what we can see is an increasing gap between wages in Greater Manchester and the wages in England once we move up the pay scale. This implies that there are shortages of higher paid jobs in Greater Manchester – possibly in part accounted for by a smaller share of the higher skilled in the workforce, but differences in the availability of higher paid jobs undoubtedly plays a part.

What is interesting is that, even though as we move up the distribution of wages there is an even greater gap for men than for women between wages in Greater Manchester and England, the gender pay gap also widens. Men in Greater Manchester are falling further behind men in England as a whole, but their pay is still rising relative to women’s in the higher end of the labour market. At the 90th percentile, the gender pay gap rises to nearly 18% in Greater Manchester, but to nearly 23% for England as a whole, well above the 14% and 19% gaps found at the median level. Meanwhile, women’s wages in Greater Manchester at the 90th percentile are around 10 percentage points less than for England as a whole, but for men, the discount is over 15 percentage points.

Figure 3. Variations along the wage structure in Greater Manchester – by relative wages and the gender pay gap. Source: ASHE hourly earnings excluding overtime (accessed via NOMIS) (author’s own calculations)

Higher skilled women are particularly reliant on the public sector for access to higher level jobs; around three fifths of all women in employment with a university degree work in public services, including public administration, education and health and social care. The Greater Manchester economy has been rebalancing away from the public sector over the past decade due on the one hand to cuts within and outsourcing from the public sector and, on the other hand, to growth in the private sector. Numbers of jobs in the public sector have remained at roughly the same level over the past decade despite population growth, but jobs in the private sector have grown by around 13% for men and 16% for women. The public sector tends to pay notably higher wages for women due to the highly skilled composition of the workforce, and also offers more opportunities to work part-time in higher level jobs. However, since 2010, there has been a decline in both job opportunities and pay in the public sector, with particularly negative consequences for women who make up most of the workforce.

Key messages

There are three issues of relevance for the Greater Manchester social and economic strategy. The first is that promoting the adoption of the voluntary living wage could have a major impact on women’s earnings, particularly those residing outside the central area where the share earning below the living wage often accounts for a third or more of all women in work. This policy promotes gender equality, but also benefits the many low paid men in Greater Manchester and the many poor households that increasingly rely on women’s earnings to make ends meet.

The second message is that Greater Manchester needs to expand the number of high-skilled and high-paid jobs in line with Greater Manchester’s strategy, but there is a danger that this could further exacerbate gender pay inequality if the main beneficiaries were to be men. The gender pay gap widens at the top of the distribution even though men’s wages in these higher levels are much less than found for the nation as a whole. A policy to expand opportunities to women is thus vital to ensure against widening gender pay inequality.

Thirdly, more needs to be done to re-establish good pay and conditions in the public sector, and also in outsourced public services. These areas of employment are particularly important for women. Public sector pay and conditions are primarily set at national level, but more can be done at local or regional level to improve conditions for workers in outsourced services through commissioning policies.

This article was originally published in On Gender, a collection of essays providing analysis and ideas on taking a gendered lens to policy in Greater Manchester and devolved regions across the UK. You can read the full publication here.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.