On Monday the latest round of talks on the EU-US free trade agreement get underway. Gabriel Siles-Brügge and Ferdi De Ville challenge the proclaimed benefits of this much-vaunted deal. Rather than represent ‘the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine’, they argue the deal is a distraction that is unlikely to significantly boost growth.

‘This is the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine.’ ‘This is a once-in a generation prize and we are determined to seize it.’

With such bombastic language being used, respectively, by EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht and David Cameron to describe the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the stakes are high for the third round of talks between the EU and the US.

While critical voices in the UK press have raised concerns about ‘a treaty that would let rapacious companies subvert our laws, rights and national sovereignty’, so far less has been said about the overblown economic arguments in favour of the agreement.

Policymakers and politicians are wont to quote the headline figures that the TTIP will yield €119bn a year for the EU and €95bn a year for the US. This, it is said, translates into €545 of extra annual disposable income for a family of four in the EU and €655 per household in the US – but only by 2027, which is rarely mentioned in the official rhetoric.

These figures come from an impact assessment conducted by the European Commission. This in turn draws on economic simulations into transatlantic trade, undertaken at the Commission’s behest by ECORYS and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). We argue that it is precisely these simulations that are on pretty shaky ground.

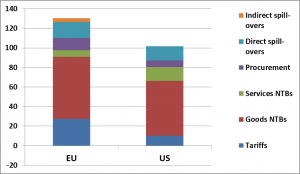

The graph below shows where the expected gains from trade opening come from. Rather than the elimination of tariffs (taxes on imports, in blue) it is the scrapping of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in goods (in red) and services (in green) that promises to deliver most of the economic gains from the agreement.

In other words, the gains from the TTIP will largely derive from eliminating restrictions to trade that arise from the different ways that the EU and the US regulate their economies.

Source: author elaboration, using data from the CEPR

Figure 1 – Annual output gains from the TTIP by type of liberalisation (€ billions)

The calculations are premised on the assumption that 100% of tariffs, 25% of goods and services NTBs and 50% of government procurement restrictions will be eliminated. This is, however, a highly optimistic assessment, for at least two reasons.

Firstly, the Commission’s impact assessment notes that only 50% of total NTBs are even ‘actionable’. Given that ‘actionable’ is defined very broadly as anything ‘within the reach of policy to [address]’, eliminating 25 per cent of NTBs suddenly looks a whole lot harder; it means that the TTIP would have to eliminate half rather than just one quarter of existing policy-based non-tariff restrictions to trade.

In light of the history of EU-US transatlantic cooperation, which has so far yielded only a patchy record of cooperation in the sphere of economic regulation, this is a tall order. After all, what the TTIP is seeking to do is to align the way in which the EU and US economies are regulated, which is often an extremely politicised area.

EU and US standards are poles apart in some domains. The sale of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) is extremely restricted in the EU due to the reliance on the ‘precautionary principle’ while ‘science-based’ assessments of risk in the US mean that they are widely available there.

Of course, in a number of areas standards and regulations are broadly seen as comparable. Car safety standards might be different but accomplish much the same, uncontroversial task.

But even in these cases, the TTIP faces the additional hurdle of multiple and overlapping jurisdictions over regulatory matters that characterise the US federal system. Such things as emissions standards for cars (as well as many other aspects of the regulation of the economy) vary between US States. Whether US trade negotiators, which represent the federal government, will be able to come up with a ‘coherent’ package in the context of the TTIP remains to be seen.

This brings us to our second contention with the claimed benefits. The ECORYS study’s predictions for gains from NTB liberalisation finds that the gains are very much dependent on whether all sectors are liberalised. In their words, ‘sector inter-linkages strongly affect the results’.

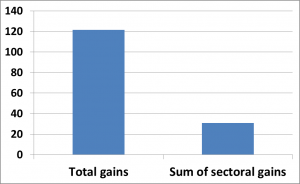

As the chart below shows, the total gains from NTB elimination (assuming all sectors are liberalised) are around four times larger than the sum of sectoral parts (if the gains from eliminating NTBs in each sector were added individually).

So unless there is liberalisation across the board – unlikely given a number of problem sectors as noted above – the gains from the TTIP are likely to be much smaller than hypothesised.

Source: author elaboration, using data from ECORYS.

NB: This study assumes that all ‘actionable’ NTBs will be addressed (i.e. 50 per cent of EU-US NTBs), rather than just 25 per cent (as in the Commission’s impact assessment and the CEPR study). But this does not detract from the overall argument about synergy effects.

Figure 2 – Annual income increases for the EU from NTB elimination (€ billions)

All this leads to the conclusion that pushing for trade liberalisation is not the silver bullet to our economic woes that policymakers and politicians would have us believe it is.

In the case of Britain specifically, Craig Berry has recently argued that the TTIP is unlikely to address the growing trade deficit in the long-run; rather, it fails to address underlying competitiveness issues that would be best tackled through additional investment in technological innovation and manufacturing.

To rephrase economist Paul Krugman, the current obsession with free trade is a distraction, and a dangerous one at that.

[…] from the University of Manchester and Dr Ferdi De Ville from Ghent University, have undertaken research to show that the job and growth figures are “vastly overblown and deeply […]