The Department for Transport (DfT) recently released their long-awaited Decarbonising Transport plan. In this blog, Dr Cristina Temenos and Dr Joe Blakey outline how its technologically-optimistic vision risks locking in high-carbon futures, overlooking transport inequalities, and opportunities for joined-up thinking and the precautionary principle.

- DfT’s Decarbonising Transport Plan makes some welcome proposals, but it is overly optimistic, gambling on future technologies to avoid fundamental changes to our lifestyles today.

- Policymakers should focus on tackling transport inequalities: both in terms of unequal access and the high-emitting practices of an elite few.

- There are opportunities for combining action with COVID-19 recovery – ensuring that public transport is attractive, spacious, and well-ventilated and that it and active travel schemes are properly resourced.

The Department for Transport’s plan, Decarbonising Transport: A Better Greener Britain, sets out the UK Government’s strategy for reducing carbon emissions in the transport sector. Pre-pandemic, the transport sector was responsible for over 25% of the UK’s carbon footprint and the largest contributor, which has hardly changed in the past three decades. Radical action is urgently required. The plan has many welcome proposals, such as the Zero Emission Vehicle mandate and support for car sharing schemes. However, as Mike Thompson, the Climate Change Committee’s Chief Economist notes, “the devil will be in the details”. Three key details to scrutinise are the risky techno-optimism, the role of inequality, and a need for joined-up thinking.

Can we have our cake and eat it too?

The DfT wants lifestyles to remain the same throughout any decarbonisation process. Holiday flights, car culture, and ongoing development are singled out as important aspects of British life to protect. But can we maintain high consumption lifestyles without high consumption of carbon, and is that what people want? Recent surveys of employees have shown the desire for more flexible work is correlated directly to commute times – longer commutes equals stronger preferences for flexible and remote work options. Previous work has also shown that in order for decarbonisation to meaningfully reduce emissions, it will need to be linked up to shifting infrastructure investments in active and public transport and it will entail a degree of lifestyle change.

Reckless technological optimism

Mobility transition requires more than just technological innovation. Currently, the plan relies heavily on electric vehicles (EVs). EVs produce fewer emissions over their lifetime, but decarbonisation needs to happen sooner than the technology might proliferate, with people likely to hold on to petrol and diesel cars for a while. It’s also not a strategic use of our future limited zero-carbon electricity supply and distracts us from other more-inclusive modes of transport.

Faith in technological solutions risks complacency in the present. Consider aviation; the plan lauds investment into sustainable aviation fuels and research into zero-carbon flights as a solution while passenger numbers are predicted to grow. This is despite later acknowledgement that the ‘solution certainty’, ‘infrastructure maturity’ and ‘fleet penetration’ of these technologies are all very low. The crux of this strategy is wishful thinking. But we can take certain action now in the form of demand management, such as frequent flyer caps, to prevent more dangerous levels of warming.

For aviation, offsetting (balancing emission with removals or reductions elsewhere) is treated as an insurance policy where “residual emissions […] will be offset by credible, verifiable and demonstrable” schemes. Negative emissions technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, are really the only form of offsetting that come close to this criteria, but these are exceedingly expensive and it is uncertain if they can deployed at scale. It forms another high-stakes technological gamble to avoid the sensible precaution of action today.

Decarbonisation for who?

Inequality is largely overlooked in the plan. Access to transportation choices is highly uneven based on deprivation levels. However, the only nod to this issue is a requirement for consultation on traffic reduction and an Ofgem recommendation to socialise the costs of electricity network upgrades (for things like e-vehicle charging stations) across all bill payers. There is a real opportunity to ensure that the benefits of decarbonisation are equitably distributed across a broad section of society and that linked up planning could potentially address not only the climate crisis but also issues of transport access. Too much focus on techno-fixes without consideration of uneven access, either through affordability or geography, risks perpetuating ongoing issues of transport justice.

We know that transport emissions are greatest for the richest in our society. As Oxfam noted, the richest 10% use around 45% of energy linked to ground transport, and 75% of the energy linked to aviation. Tackling high-emitting mobility habits of the rich – such as the aforementioned frequent flier cap, bans on unsustainable high-carbon luxuries such as SUVs, or more fundamental wealth redistribution to simultaneously tackle structural inequalities – would conserve the limited remaining carbon budget for all.

Linked up planning

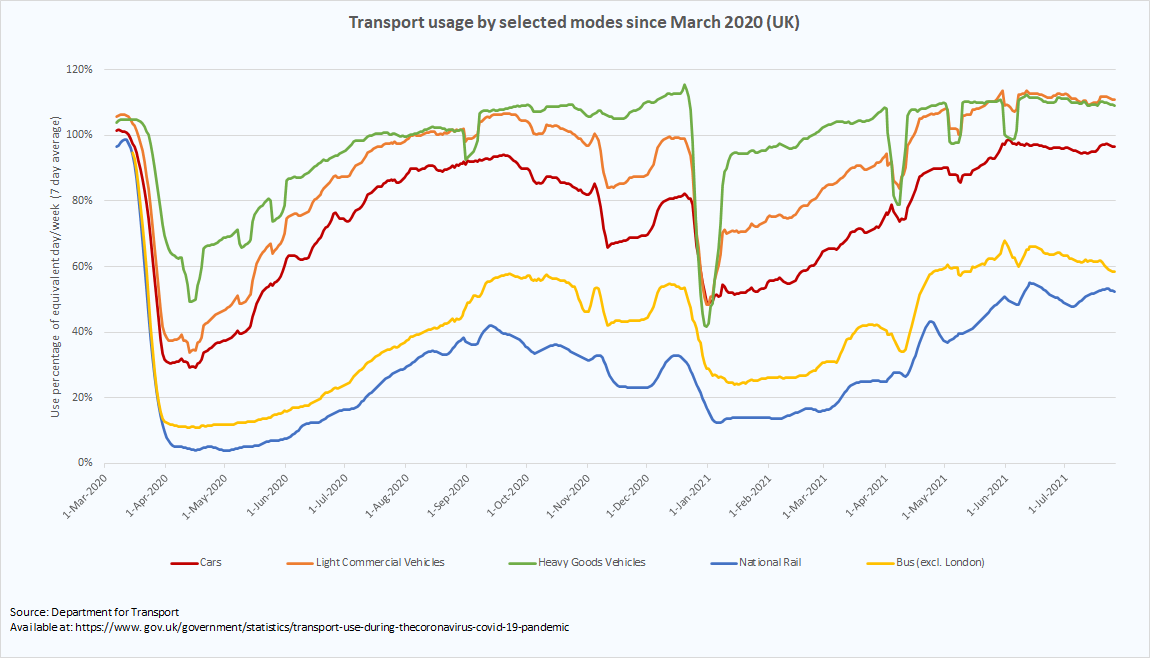

The plan’s first priority is a welcome one: accelerating the shift to public and active transport, making them “the natural first choice for our daily activities”. However, the effect of COVID-19 on our travel choices tells a different story. Reductions in automobile traffic have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels (even exceeding them in places). Public transportation, meanwhile, remains below pre-pandemic levels (see below).

The uptick in driving and low public transport levels are correlated. Many have chosen to avoid public transport to reduce their risk of catching COVID-19 – and some of these people will have turned to driving instead. It is too soon to tell when or how this reticence can be overcome. To deliver this priority, it is imperative that transport consultations take into account public health considerations, establish commitments to healthy transport infrastructure (such as adequate spacing and ventilation), and ensure that the data used to model potential ridership is not reflective of current low-levels.

Similarly, during the pandemic, cycling in urban areas has gone up by as much as 22% in London and 20% in Greater Manchester. Some routes in GM have shown increases of up to 50% for weekday trips and 62% on weekends according to unpublished data from TfGM. Numbers dipped as car traffic increased, with the decline in vehicles creating room and assurance for cyclists to take to the streets and suggesting a correlation between cyclists’ concern for road safety and ridership levels. Infrastructure upgrades and prioritising pedestrianisation and active transport routes should be a priority. This must be coupled with a plan and resources dedicated to ensuring the spaces created for cycling and walking are safe and clear of vehicles parked in bike lanes or on pavements.

In Europe, investment in cycling infrastructure has proven successful. Paris has seen a 52% ridership increase after a €300,000,000 investment in cycle lanes, and Amsterdam has prioritised cycling infrastructure. UK cities have had more piecemeal interventions. However, a 2020 survey showed that (pre-pandemic) the best UK cities to cycle in were Lancaster and Exeter – both cities that had been selected to promote cycling in 2005, demonstrating that targeted long-term investment produces results when it focuses on linked up planning across equity and infrastructure. Recent changes to local authorities’ ability to fine drivers parking in cycle lanes and the anticipated change of legislation prioritising pedestrians in a new road hierarchy are welcome interventions to help shift mobility culture away from cars towards active transport.

A matter of space and time

The DfT plan is a useful roadmap for thinking through multi-scalar strategies to achieve net zero and focus on each of the six priority areas. Policy approaches for low-carbon transitions work best when there is agreement across the local, regional, national, and international scales. To make active travel the first choice for trips, for instance, decarbonisation initiatives need to be linked up with spatial planning at the regional and local levels. There needs to be space made for alternative modes of transportation, and encouragement from government and community leaders to ensure these spaces are valued in the community by a wide transect of the people.

Ultimately, time is critical: we need to make these cuts quickly. With transport emissions hardly changing in the last 30 years, the renewed optimism that we can innovate our way out of a climate crisis without compromise seems misplaced. Each passing year results in a greater depletion of the global carbon budget to stay within safer levels of warming. We can’t gamble on the future, but should follow the precautionary principle by delivering radical cuts now.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.