COVID-19 has seen an increased vulnerability to cyber crime. In this blog, originally from our On Digital Trust publication, Professor Emma Barrett, Professor Danny Dresner, and Dr David Buil-Gil outline why victims of cyber crime need greater protection, including a raft of ‘CPR’ measures designed to help them recover quickly.

- Cyber crimes cost billions of pounds a year, and cause emotional and psychological distress to their victims.

- While there exist robust measures for dealing with large scale cyber espionage, there is little support for victims of everyday cyber crime.

- A humane recovery support package is needed, which recognises the central role digital devices and information play in our lives.

Recovery support for victims of cyber crime is unevenly distributed. Large organisations can call on the resources of the state, whereas support for the thousands of ordinary victims is scarce. The impact on citizens’ security and trust can be profound. It’s time for an urgent focus on everyday cyber crime victims.

Financial cyber crimes are rising rapidly in scale, complexity and social impact. The 2017 Annual Fraud Indicator estimated that frauds represent a cost to the private sector of £140 billion a year, the public sector £40 billion, and individual citizens £6.8 billion. Over half of all frauds are committed online. How are these crimes perpetrated, and what impact do they have on ordinary victims?

Insecurity, opportunity and exploitation

Criminals profit from information insecurity and poor cyber hygiene. Use of insecure passwords puts you at risk. But even a strong password won’t help if the website you’ve entrusted your data to doesn’t adequately protect it – if it’s hacked, your details can be leaked. Cyber criminals can then use an automated technique called ‘credential stuffing’: trying your leaked email/password combination on multiple websites, in the hope that you reuse the same credentials (as many of us do). And there’s phishing emails containing links to sites which can trick you into revealing your login details for banking or other potentially lucrative sites.

As well as exploiting our mistakes, cyber criminals have an array of psychological tricks up their sleeves. For instance, they take advantage of periods of consumer uncertainty when organisations are disrupted. The massive IT failure that prevented British bank TSB’s customers from accessing their accounts, the 2018 breach of British Airways’ customer data, and the collapse of Thomas Cook in 2019, were all opportunities for cyber criminals to exploit customer fears. Consumers received phishing emails, warning them to update their credentials immediately, with a link to an authentic-looking but bogus website. Even access to a victim’s IT is not essential. Posing as trustworthy representatives from the affected organisation, criminals phone potential victims, arguing convincingly that the only way to avoid loss in a follow-on attack is to transfer money to a ‘safe’ account, which, of course, belongs to the criminals.

And then there are internet-age blackmail schemes and hustles. ‘Sextortion’ criminals and dating fraudsters deliberately engage in the construction of trust with their victim, sometimes over weeks or months, with the express intention of betraying it. In the case of dating fraud, where a criminal feigns a romantic attachment, the realisation of what has happened can leave victims not just financially but psychologically devastated.

In every case, cyber criminals get at your cash by exploiting your trust: trust that people won’t try to steal your password, trust that a company will keep your data safe, and trust that the person you’re interacting with online is who they say they are and is being honest about their motives.

The emotional impact of cyber crime

Interpersonal cyber crimes are a betrayal of trust, and the emotional impact of ‘cyber betrayal’ can be as profound as betrayal in the physical world. Victims have reported feeling distressed, anxious, powerless and angry. They can become depressed, even suicidal, and lose trust in others. One victim of a dating scam told researchers she found the experience so traumatic she likened it to being “mentally raped”.

A common and corrosive reaction is embarrassment. Victims may ask themselves if they might have been partly to blame. If you trust a stranger and they let you down, does it say more about you and your gullibility than about the cruelty of your betrayer? Were you guilty of ‘blind faith’? An employee of a company already in financial difficulty was devastated at the thought that she had let colleagues down when she realised she’d entered company credit card details into a bogus site.

In dating scams it’s particularly hurtful to realise that a relationship apparently built on openness, intimacy, and trust is instead founded in deception. And the potential that the situation might become public, opening the victim up to ridicule or pity, can also evoke deep feelings of humiliation.

Shame has consequences. Victims may be reluctant to confide in people around them, who might otherwise offer practical and psychological support in the aftermath of a crime. And they may also fail to report crimes to the authorities for fear of ridicule or belief that police would do nothing. No wonder cyber crimes are vastly underreported.

Unsurprisingly, cyber crimes can leave people fearful. Those with prior experience of being a victim tend to be most fearful of such crimes, according to a recent European study. Fear can corrode trust, even in people who might be trying to help. Some victims might be afraid of ever logging on again.

How can people become resilient to the effects of an attack? We need the ability to recover quickly: technically (cleansing devices, software and data to erase any malware), financially (regaining control of bank accounts and plugging the holes), and psychologically.

Asymmetry of support

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has responsibility for supporting cyber security in the UK, and when large organisations fall victim to cyber-attacks, it steps in to help. The scale of resources devoted to mitigation, investigation, and recovery depends on which of six categories the incident falls into, from a ‘Category 1 National Cyber Emergency’ to a ‘Category 6 Localised Incident’. The most serious, nationally important incidents (such as the 2017 NHS ransomware attack) prompt a specialist incident response, drawing on a vast array of government resources, working with investigators in NCSC’s parent organisation GCHQ to identify the attackers, coordinating with overseas partners, and helping the victim organisation get back up and running. Even a ‘Category 4 Substantial Incident’ affecting a medium-sized organisation may qualify for NCSC support.

But what about everyday victims – small businesses and ordinary citizens, for example? They’re in categories 5 and 6. They will be told to report the crime to Action Fraud, the national reporting centre run by City of London Police alongside the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau, who will then allocate the case for investigation.

Or so you would like to think. In practice, the scale and complexity of cyber crime is such that a report may be logged and even passed to local police, but they may not have the resources to investigate. Fewer than one in fifty reports results in a suspect being caught, and a 2019 undercover enquiry by The Times newspaper revealed that contractors used by Action Fraud to collect reports treated victims, often defrauded of huge sums, with disdain. Once they put the phone down, call handlers reportedly mocked victims as “morons”, “screwballs” and “psychos”. No wonder victims told The Times they felt ignored and disrespected. If this is how victims perceive they will be treated, trust will further be eroded. Anger, humiliation and anxiety will be associated with the authorities, as well as the cyber criminals.

Cyber CPR

As well as doing more to support the effective investigation of cyber crime, we also need to invest in helping victims recover – practically and psychologically – in circumstances where prosecution is not possible. We need to recognise that most citizens who fall victim will have little by way of protective or contingency methods. Whilst resources to recover will be at hand for critical infrastructure, food, and finance, ordinary people who have suffered an attack may find themselves excluded and unable to engage with public services, shopping and entertainment, banking and other financial services. A proliferating quagmire of prevention advice is often difficult to navigate, conflicting, and ironically assumes that the person needing it will have internet access, when in practice they may have lost all safe access or may be too nervous to log back online. Many will not have alternative resources to turn to; cyber-attacks, therefore, create a new kind of digital exclusion.

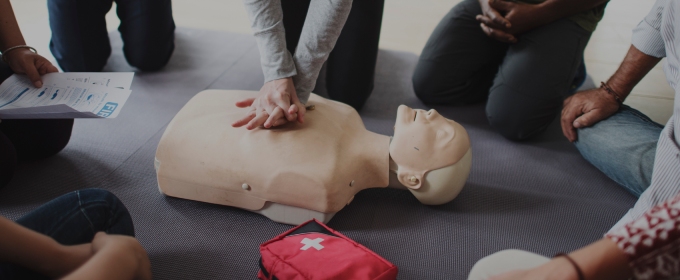

It’s time to consider giving unprepared citizens the capacity for self-help. We propose development of a ‘Cyber CPR kit’ with advice and tools to help victims recover. Local police cyber crime units may be the ideal owners and distributors of this in the first instance, and it could become an offering from local cyber resilience centres of the type already established in Scotland, London, and Manchester.

A recovery kit needs to be practical, recognising that victims’ work and domestic lives are dependent on multiple digital accounts, including banking, social media, and e-mail. And they might rely on multiple devices to access these: laptops, tablets, smartphones, as well as ‘Internet of Things’ devices such as cameras and Fitbit-type devices. An increasing number will depend on internet-enabled critical medical equipment such as pacemakers and insulin pumps. Some or all of this will be unavailable after an attack. Cyber CPR should recognise that a victim may be cut off from internet-based services, including those that can help recovery when a problem occurs. The kit may contain a variety of technical fixes and advice for quick action (think ‘sticking plasters’) and powerful recovery tools (think ‘defibrillator’ or ‘EpiPen’).

Most of all, the design of the kit needs to be humane. It should demonstrate empathy with the psychological and emotional suffering experienced by victims and provide practical steps to help them rebuild trust. This means explaining that the maelstrom of emotions they may be feeling is normal, encouraging them to use social support and, where victims are socially-isolated, providing such support. It means being honest about what the police can and cannot do, but reassurance that they are doing the best they can.

The crime may be virtual. The harm is real.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.