Every day, children are exposed to levels of pollution, both during their journeys to and from school but also in playgrounds and classrooms. Results from a new literature review carried out by The University of Manchester suggests traffic-related air pollution, specifically particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), are detrimental to cognitive functioning in children (particularly working memory, a type of short-term memory essential for completing tasks). Here, on Clean Air Day, Professor Martie Van Tongeren, Dr Luke Munford and Dr Nicola Gartland put forward a series of recommendations to reduce our children’s exposure to dangerous levels of air pollution.

- Children exposed to higher levels of air pollution at school show less developmental gains in working memory than children exposed to lower levels of air pollution at school.

- National, devolved, and local governments should prioritise the reduction of traffic-related air pollution near schools in order to provide all children with the opportunity to reach their maximum potential.

Why are we interested in primary school children?

Children are more at risk of exposure to air pollution and are more vulnerable to its effects in comparison to adults. Children breathe more air per unit of body size because they have a higher breathing rate and are more physically active. Children spend up to 8 hours a day at school; therefore, schools represent an important location for the study of the effects of pollution on children. Our review of the available scientific literature has also shown that exposure levels at school do have a significant effect on children’s cognitive development.

What pollutants are we worried about?

Traffic emissions include factors such as engine exhaust and brake and tyre wear. It is estimated that 30% of particulate matter in European cities comes from road transport. Road transportation is also responsible for the release of other potentially harmful pollutants including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx).

How do we measure cognitive development in children?

We measure cognitive development using working memory and attentional control. Working memory is the ability to keep information in mind temporarily and to use it for the completion of mental tasks. Attentional control is the ability to focus attention on specific stimuli or a wider goal for an extended period, and to ignore distractions. Both faculties have rapid trajectories of development during childhood. These skills are essential for effective learning in schools, and levels of working memory in particular have been found to predict later academic achievement.

What does the existing literature tell us?

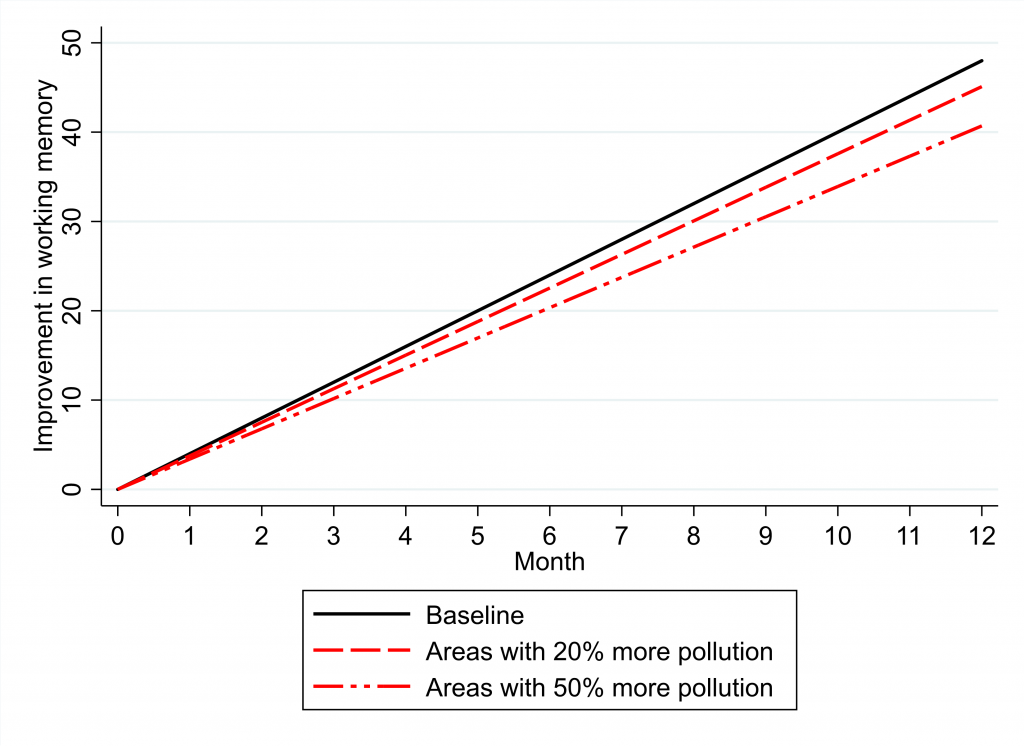

Findings suggest that indoor and outdoor PM2.5 negatively influences cognitive function (working memory and attention), indoor and outdoor NO2 adversely affects working memory, and while PM10 evidence is limited, it suggests potential wide-ranging negative effects on attention, reasoning and academic test scores. The relation between traffic-related air pollutants (TRAPs) in and around schools and working memory becomes stronger when working memory is assessed over longer time periods. Therefore, TRAPs appear to hamper the developmental trajectory of working memory, and hold the potential for continued divergence in working memory with age, and knock-on effects in academic achievement.

What do our models predict?

We show that if outdoor pollution around schools in Greater Manchester increased by 20%, the rate of development of working memory slows down by around 6%. This suggests that a 20% increase in outdoor air pollution could slow down the rate of development among children by around 3-weeks in a 12-month period (assuming linear growth). If pollution increased by 50%, the rate of working memory development slows down by around 15%, equivalent to around 7-weeks in a 12-month period. We observe similar predicted effects for increases in indoor air pollution; a 20% increase in indoor air pollution slows down the growth of working memory by around 5%. We also show that the opposite is also likely to occur – that a reduction in pollution in and around schools will lead to an improvement in children’s working memory.

Recommendations to policymakers

- The best way to reduce traffic-related air pollution around schools is to reduce the number of people driving to schools to drop off and collect children. Cutting the number of car journeys will reduce both exhaust emissions and emissions from tyre wear.

- We recommend that parents and children should be encouraged and supported to find active modes of transport for school journeys, such as walking or cycling.

- Active transport has a double impact as it improves brain and cognitive development in children and has a direct positive impact on physical and mental health for both parents and children. These benefits should be used by local authorities to promote uptake of active transport.

- Local authorities can promote healthy transport choices by building safe infrastructure, such as cycle lanes and appropriately lit walking routes.

Schools could be designated as ‘Clean Air Zones’ in order to reduce all traffic passing nearby schools.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.