The general election earlier this month saw another record breaking increase in the ethnic diversity of Members of Parliament. Here, Maria Sobolewska looks at what lead to this increased diversity and lays out a path for further progress.

- The main difference between the 2015 and 2017 elections was how the candidates were selected

- The Representative Audit of Britain data showed the usual selection process to disadvantage minorities

- 71% of 2015 white candidates were asked to stand by their party, while this was true for only 55% of ethnic minority candidates

- To improve their ethnic diversity in Westminster, parties will likely need to rely on centralised procedures for candidate selection

For those who study ethnic minority representation in Britain, two things stand out in the 2017 election. Firstly, all but one ethnic minority MPs got re-elected. This can be linked to the fact that – especially on the Conservative benches – ethnic minority MPs are now more likely to have safe or winnable majorities, rather than having to defend marginal seats. Secondly, a new batch of 12 ethnic minority MPs continue the trend of the growing ethnic diversity of Westminster. But, what these two new developments have in common is that they are a result of centralisation of party candidate selection.

Comparing elections and interventions

It is rare for political science to benefit from natural experiments, particularly where data from both before and after are available. Yet, the 2017 general election offers such an experiment for parliamentary representation of ethnic minorities. The 2015 and 2017 elections were fought very close in time, on the same constituency boundaries, with virtually unchanged electorate in each constituency.

The main difference between these two elections was how the candidates were selected. In2015, the parties knew that the election was coming and thus had time to let the traditional constituency selection process take place. Applicants from a centrally approved list could apply for multiple vacant seats and bar any exceptions- such as when the seat was declared an All Woman Shortlist for Labour- local constituencies could choose relatively freely from the applications made.

In the run-up to the 2017 election, however, both the Conservative Party HQ and Labour’s National Executive Committee (NEC) made emergency provisions which largely scaled down local selectors’ influence. Conservatives gave shortlists of three applicants to choose from to every marginal, target, and retirement seat and simply nominated candidates for the rest. Labour encouraged 2015 candidates to stand again, but NEC took part in all other selections (and were the only selectors in case of retirement seats). The main parties had made various efforts to increase diversity of their candidates and MPs in the past, but all these efforts have- with the exception of Liberal Democrats- came from the central party. David Cameron’s mission to detoxify and modernise the Conservative party is a case in point: he tried (but failed) to introduce a central, diverse, list of priority candidates; and as a result of his efforts the Conservative minority representation increased from 2 to 11 MPs at the 2010 election as seven of these new MPs hailed from the failed central list.

The scale of the problem

But, how serious is the problem of ethnic disadvantage at the stage of selection? Multiple stories of discrimination at the stage of candidate selection emerge from interviews with minority politicians. In 2015, this problem was investigated on a larger scale by the Representative Audit of Britain project, which conducted a survey of all candidates standing on behalf of the main political parties in Britain (including UKIP, Green and regional parties). The data contained 97 ethnic minority candidates from all parties, giving us an unprecedented insight into whether the selection process works fairly.

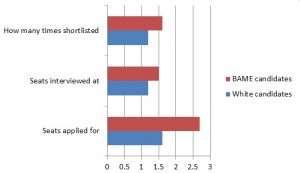

What the Representative Audit of Britain data showed is that the usual selection process disadvantages minorities. Looking at figure 1 we see that minority MPs had to – on average – apply for more seats, interview in more seats and contest more shortlists than their white counterparts before they were successfully nominated. And because the data only include candidates, it is likely an under-estimation of the problem. Such a pattern would strongly suggest that ethnicity is a disadvantage and that many more ethnic minority politicians were likely to fail to gain a seat nomination altogether.

Figure 1: Number of seats applied for, interviewed for and shortlisted for, before successful nomination; by candidate ethnicity (2015 general election)

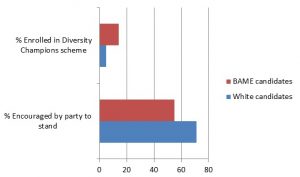

The second indicator that the usual party selection procedures may be discriminatory is the seeming lack of encouragement for minority candidates. Figure 2 presents data showing that while 71% of white candidates were asked to stand by their party (whether on local, regional or national level), this was true for only 55% of ethnic minority candidates. Although more minority candidates benefitted from being enrolled in Diversity Champions scheme than their white peers, these programmes had a limited reach with overall only 19% of all candidates having taken part.

Figure 2: Percentage of candidates who were encouraged by party to stand, and those who benefited from diversity programmes; by candidate ethnicity (2015 general election)

Why the disparity?

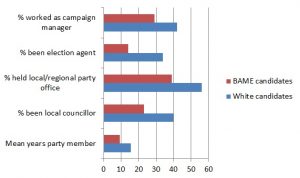

But, can this disadvantage be explained by prejudice alone? Obviously there are some alternative explanations to why ethnic minority MPs struggle with the traditional selection procedures. They are on average younger than the white candidates, less experienced and with fewer years of party membership and activism behind them (on average 9.3 years in contrast to 15.5 years of white candidates). They are also less likely to have relevant experience: only 23 per cent were a local councillor, while 40 per cent white candidates have this sort of experience (see Figure 3).

However, given ethnic minority populations as a whole have a younger age profile than the white British population, and has a fairly recent history of immigration, it is unlikely that these disparities in level of experience will close very quickly. To wait for this population to reach comparable levels of political experience to the white British population would certainly stall the nomination and election of more ethnic minority candidates for at least a decade. What 2017 shows us is that if parties want to continue to improve their ethnic diversity in Westminster, they will likely need to rely on centralised procedures for candidate selection in the future. It also shows us that they are willing to do so.

Figure 3 Political experience by candidate ethnicity (2015 general election)

- The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE)