The concept of ‘inclusive growth’ – developing an economy that works for all – is one that is increasingly gaining ground. To make it a reality, however, we need a much more collective approach and one that industry and employers commit to, say Ruth Lupton and Ceri Hughes.

Ambitions and appetite

Although she didn’t say the words ‘inclusive growth’, Theresa May’s speech at the Conservative party conference last week signalled broad support for this emerging agenda. In a speech heavily focused on building an ‘economy that works for everyone’, she heralded a new industrial strategy and infrastructure spending to ‘rebalance the economy across sectors and areas in order to spread wealth and prosperity around the country’, pledged to crack down on tax avoidance and protect worker’s rights, and reiterated her widely welcomed proposals for consumer and worker representation on company boards.

It remains to be seen how ambitious May is prepared to be, and whether her backbenchers will support her. But our research suggests that she is right in thinking there is an appetite to address problems with the way the economy is working and how the benefits of economic prosperity are shared.

Local legacies

For the last six months researchers at the Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit have been consulting with people across Greater Manchester (GM) to develop an understanding of some of the things that might be done locally to make growth more inclusive and our new report is out today. The GM city region is a very good example of an area affected by the problems that Mrs. May says she is trying to solve.

Despite GM’s impressive revival since the 1996 IRA bomb, many parts of this former industrial powerhouse are still dealing with the legacy of de-industrialization and the effects of economic restructuring, including low paid and precarious work for those at the lower end of labour market. Some areas have been left out in the cold as new jobs and developments have been concentrated in the urban core. While the pitfalls of a flexible labour market affect areas across the UK, Greater Manchester has an employment rate far below the average – Manchester, Oldham and Rochdale all had rates below 65% in 2015 compared to a UK average of 73.5% – and 22.5% of jobs were low paid in 2014.

The people we spoke to recognized the scale of the challenge and saw that these could not all be solved locally. Nonetheless the transfer of powers and funds to local areas and the election of a new city-region mayor were seen as an opportunity to set a new agenda.

Different interpretations

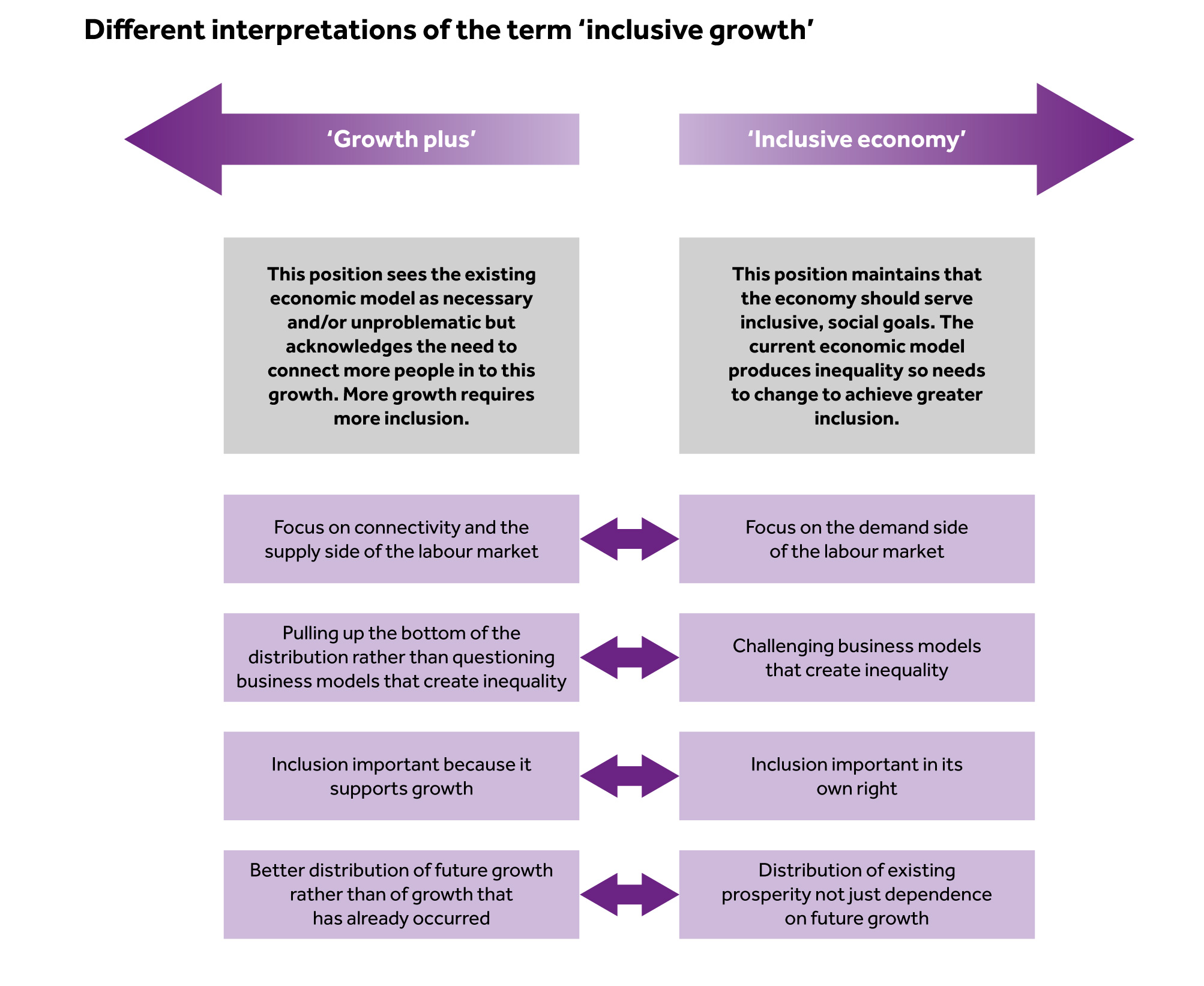

A clear message from the consultation was that inclusive growth can be interpreted in different ways. Some people take quite a narrow view, advocating only after the fact strategies to connect people in to existing growth. We call this a ‘growth plus’ version of inclusive growth. Meanwhile others are using the term much more broadly, and point to the need to engage with the nature of economic growth, to promote different forms of business organization, and decent employment standards to build a more inclusive economy. Both versions of the agenda can achieve some good where they are pursued in earnest, but an ambitious shift in the way that we think about the economy is needed.

Engagement to tackle poverty

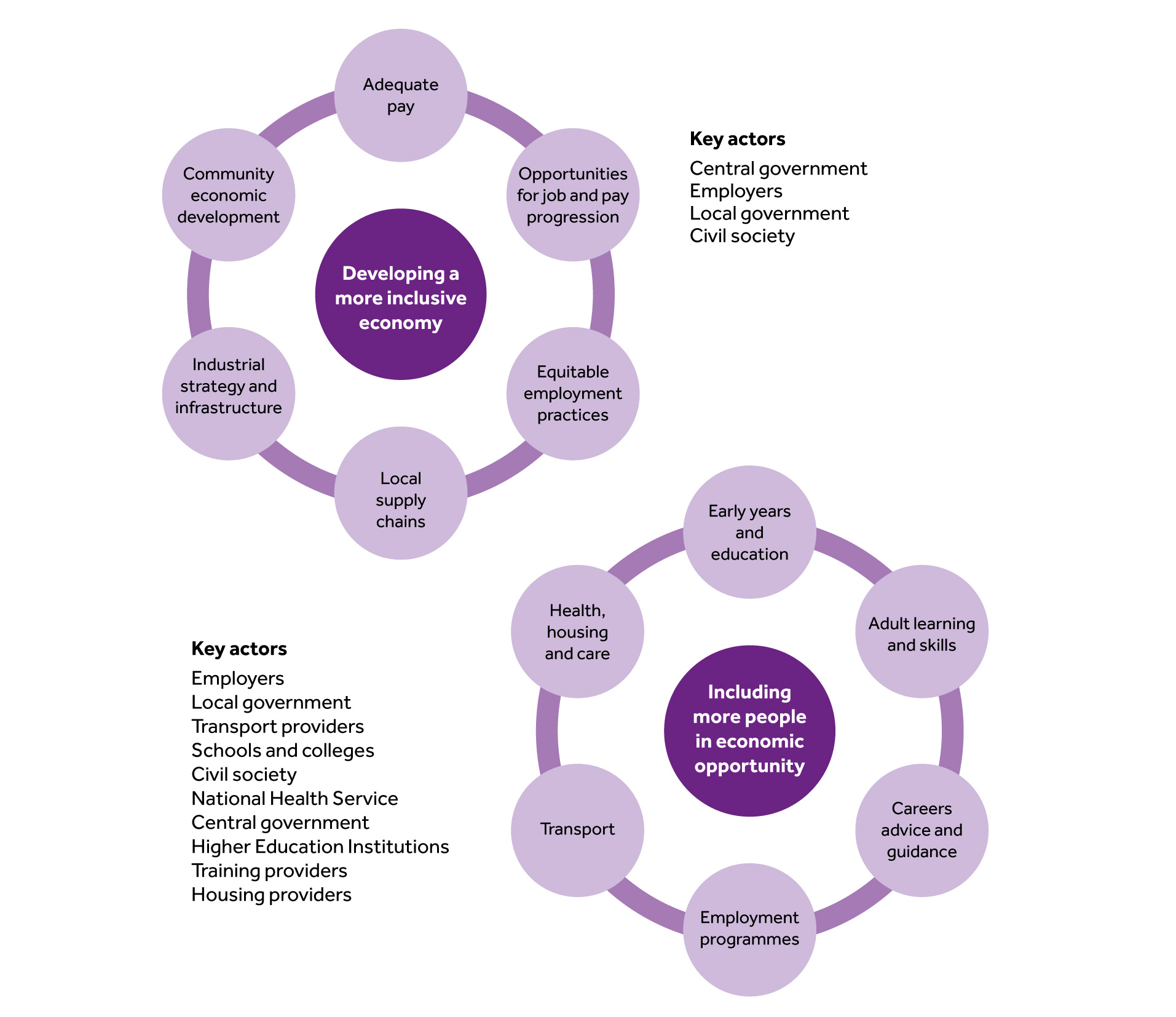

In our consultation, people recognized that while a strategy to enable more people to participate in economic opportunity can take us part of the way, engagement with the nature of economic growth is fundamental to tackling poverty. Greater Manchester needs employment growth but respondents also questioned the value of economic activity that does not lead to good jobs – ones which are secure, pay living wages and offer opportunities for progression. They did point to the need for a more effective strategy to connect people to jobs, including through offering real personalised employment support and taking action on transport costs, but they also emphasised some of the structural economic problems that would need to be addressed: low pay, uneven growth and poor prospects for employment progression. We present these as two distinct spheres of activity in an ‘inclusive growth’ strategy (see figure).

A collective endeavour

What this illustrates is that an economic strategy at the service of ordinary working people is not entirely in the gift of government, whether national or local. Building an inclusive economy needs to be a collective endeavour, requiring commitment and the resources of a much wider range of people, including, crucially, employers. That’s why it is encouraging to see that Mrs May has commissioned an independent review of employment practices from Matthew Taylor, head of the RSA. But also rather disappointing that the interim report from the RSA’s own Commission on Inclusive Growth, published last month, had little to say on the role of business and how ‘inclusive business’ can be supported. Its calls for the closer integration of social and economy policy, sustained investment in people and places and for an emphasis on ‘quality GVA’, were, however, all very welcome.

The projects and initiatives our report highlights and others underway in cities across the UK point the way to what might constitute a good economy. The momentum is building in Greater Manchester too with the new GM lead for Fairness, Equality and Cohesion, Jean Stretton, setting out her determination to pursue Fair Growth alongside social regeneration. The Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit will be working to support these developments. We welcome contact from anyone who is keen to collaborate with us.

- To find out more, email us or visit our website