It’s not how mixed our social networks are that’s the key to reducing poverty, it’s broader issues of social isolation and inequality in education we should focus on, argues Nissa Finney.

The people that we know – our social networks – have come to be seen as a resource, for social and economic support and for access to information and opportunities. One influential idea of scholarship on social networks is that it is beneficial to have a mix of people in your social network. The theory is that this opens up more opportunities and access to different types of information and support. The notion of mixing includes ethnic mix.

This idea has been taken on by those interested in immigrant and minority integration, re-cast in terms of the importance of minorities having social networks that are not solely made up of people of the same ethnic group as them. The basic idea is that the higher proportion of people that people in minorities know from different ethnic groups, the more support they will have and greater access to opportunities. This in turn will lead to greater opportunity for both socio-economic and cultural integration.

Two interesting assumptions underpin this line of argument: first, that responsibility for generating social capital lies with the individual; and second, that responsibility for integration lies with the minority.

Evidence to date is inconclusive on the significance and impact of ethnically mixed social networks and rather little exists for the UK. In a project for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation we had the specific concern of investigating how mixed social networks are related to poverty for different ethnic groups. We used recently available data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, Understanding Society (wave 3).

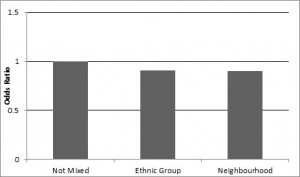

There is a clear message from the results: the probability of being poor and of being very poor is less for individuals with mixed friendship networks than for those without mixed friendship networks (Figure 1). Three aspects of mixing in friendships matter:

- having a mixed ethnic friendship network

- having friends from outside your neighbourhood

- having all friends who are employed

Figure 1: Likelihood of being poor with mixed-ethnic group and mixed-neighbourhood social networks compared to social networks that are not mixed (controlling for demographic and socio-economic characteristics)

Source: Understanding Society, Wave 3 (authors calculations)

This is the case for all ethnic groups and for people in ‘families doing ok’ or ‘struggling families’ and for ‘young solos’ and ‘single parents’. For example, having a mixed friendship network could reduce the likelihood of an individual in a ‘struggling family’ being very poor by a third compared with not having a mixed friendship network.

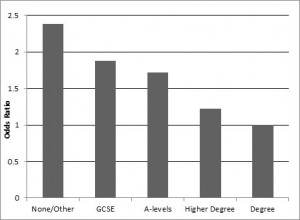

But how important is a mixed friendship network for affecting poverty compared with other factors? The answer: not very. In fact, other factors such as having no qualifications or being separated or divorced are stronger predictors of being in poverty than social network composition (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Likelihood of being poor according to educational qualification (controlling for demographic and socio-economic and social network characteristics)

Source: Understanding Society, Wave 3 (authors calculations)

And who benefits from mixed friendship networks? We found that the benefit of having mixed friendship networks in terms of the degree of reduction in poverty is felt most by ethnic groups with lowest levels of poverty (particularly the White British ethnic group), and least by those with highest levels of poverty (particularly the Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups).

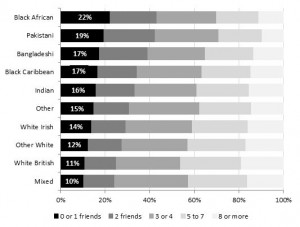

Another problem with a focus on mix is that it can miss other, more fundamental, aspects of social relations. For example, one striking result from our analysis was that social isolation is not evenly experienced across ethnic groups. Black African, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Black Caribbean ethnic groups are most likely to have only one or no close friends; as many as one in five Black African people reported having only one, or no, close friends (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of close friends by ethnic group

Source: Understanding Society, Wave 3 (authors calculations)

The number of close friends was a stronger predictor of poverty status than how mixed somebody’s social network was. Having two or more close friends reduces the likelihood of being in poverty compared to having no or one friend. This suggests that social isolation is a particular risk for poverty (or consequence of living in poverty).

This research suggests that having mixed social network composition can reduce poverty risk. However, social networks cannot be viewed in isolation and policies focusing on individual’s social networks will not be a solution for integration or inequalities. Other factors, including education and social isolation, have a greater effect on levels of poverty (as well as shaping the networks that people have access to). Strategies for addressing poverty and inequalities and promoting integration cannot rely on changing individual behaviour; there’s still a need to examine how the organisation of society means some fare well and others do not.