The debate is raging on whether London disproportionately creates or consumes the UK’s revenues. Dr Adam Leaver chips in.

Ever since Evan Davis presented Mind the Gap, a debate has raged about whether London’s dominance of the UK economy is a positive or a negative.

While my colleagues Iain Deas, Graham Haughton and Stephen Hincks have put forward the case that London is a ‘subsidy junkie’, Evan Davis has responded (see comments) that just looking at the public money spent on the city is inadequate. The revenues London generates also need to be taken into account, he argues.

“To reduce it to basics, it could be that London is more productive and as a consequence is more tax-generating and more expensive,” suggests Davis. “It thus needs extra public spending. That is not a subsidy if London more than raises the money to pay for it.”

Two issues immediately arise. First, how do we measure regional cross-subsidy when one region is so successful and requires higher levels of public service investment to sustain its success? Second, who ‘owns’ those revenues? There is an implication that higher levels of expenditure are not a cross-subsidy if that region is simply spending its own money.

The issue of cross-subsidy is difficult to measure. On a per capita measure, Londoners receive higher levels of public expenditure than individuals elsewhere in the country.

Identifiable expenditure on services per capita is higher in London than in any other English region, though figures for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are higher. On transport infrastructure expenditure, the per capita figures are: south-west £215, north-east £246, Yorkshire and Humberside £303, north-west £839, London £4895. The differences are astronomic.

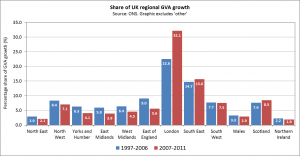

However, it is also true that London has historically generated a greater proportion of gross value added growth, and – as figure 1 shows – this has increased significantly post- crisis. Since 2007, London and the South East account for close to a half of the UK’s total GVA growth.

These figures apparently support Evan’s point. London clearly generates a significantly greater share of the UK’s total tax take. But this may be the wrong way to look at cross-subsidy, because it only takes into consideration ex post (actual) distributions. By thinking about ex ante cross-subsidies – that is distributions, guarantees, bail-outs and other subsidies that underpin activity – a different picture emerges.

These figures apparently support Evan’s point. London clearly generates a significantly greater share of the UK’s total tax take. But this may be the wrong way to look at cross-subsidy, because it only takes into consideration ex post (actual) distributions. By thinking about ex ante cross-subsidies – that is distributions, guarantees, bail-outs and other subsidies that underpin activity – a different picture emerges.

Let us look at financial services. The cost of the UK bank bail-outs is estimated at between £289bn and £1,183bn by the IMF. And the presence of a state bail-out guarantee reduces banks’ credit risk and allows them to borrow more cheaply. In 2009 alone it was estimated that this amounted to a funding cost reduction of more than £100bn for 13 UK banks.

With that level of subsidy, we might expect those industries to become world leaders. We might also then expect an influx of global talent as those subsidies allow us to pay the best wages and bonuses. We might expect foreign direct investment as global companies source here to access that talent. We might expect allied industries to spring up – lawyers, accountants, service firms, boutique establishments. We might then expect agglomeration economy dynamics to emerge as demand multipliers kick in.

Those industries would make a lot of money, and would pay a lot of tax – as would their employees. But that is a state subsidy, applied to London and not to activities prevalent elsewhere in the country.

Further, because those activities suck in talent from the regions (engineers, mathematicians, physicists and other scientists) they undermine the broad competences of non-metropolitan areas. This implies less palatable conclusions to those of Mind the Gap because gains are zero sum: to replicate the success of London, regions must wrestle power and state subsidy from it.

Let us consider another example: PFI. The problem with ‘identifiable expenditures’ as reported by the Treasury is that it does not capture the leakage of revenues out of the regions. If a hospital is built in Manchester, how much money remains in Manchester? With the example of St Mary’s – it is not a lot.

The shareholders on the St Mary’s hospital PFI were Bovis Lend Lease (50%) (HQ Kent); HSBC (25%) (HQ London) and Sodexho (25%) (HQ London). The contractors were Bovis (Design & Build) (HQ Kent), RKW (HQ Dusseldorf, Germany), WR Adams (HQ Georgia, US, but a Bovis subsidiary), Building Design Partnership (HQ Manchester) and Anshen Dyer (HQ Calif/London).

The private sector advisors were Clifford Chance (HQ London), Faithful & Gould (HQ London) and Marsh (HQ London). Financing involved the European Investment Bank, Deutsche Bank and the Royal Bank of Canada. With these foreign firms much of the money again flows back to their London offices.

So this is state money supporting London based business and employment, even when investment is in the regions. Infrastructure investment could be organised differently to the benefit of the regions, but this model has the effect of operating like a quasi-regional policy for London and the South East.

Finally, on the question of ownership: are these London’s revenues? This raises various technical questions about how we account for revenues and moral questions about proprietorial claims in a national economy. But there is clearly a regional moral hazard: the metropolitanisation of gains and the nationalisation of losses.

The UK’s ‘second cities’ are small and grow more slowly than London. The UK’s largest 2nd tier city generates around 10% of the output of London – this is the second highest level of city inequality within the EU. By this measure we have more in common with Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania or Greece than with Germany, Netherlands or Sweden.

It is just not credible to laud London as an exemplar while ignoring the role of the ex ante state subsidies that benefit London and reinforce regional inequalities.

[…] Original source – Manchester Policy Blogs […]