As part of the publication of a new working paper on the characteristics and post-16 transitions of GCSE ‘lower attainers,’ Ruth Lupton, Sanne Velthuis, Stephanie Thomson and Lorna Unwin reflect on the progress made by those with lower GCSE attainment during the 16-18 phase, and highlight the need for appropriate, high-quality post-16 provision for all young people.

- The majority of students that don’t achieve grade 4 in English and maths at GCSE remain at the same level or reach a lower level of attainment in the 16-18 phase.

- Often schools or post-16 providers get blamed for these grades.

- We need to find out more about the characteristics and experiences of learners with ‘below expected’ attainment so that policymakers can design new support measures.

Grades at Key Stage 4

This summer’s flurry of headlines about GCSE results focused on how many 16-year-olds hit the new grade 9 as well as the usual stories of the super-achievers. However, most young people didn’t open their results’ letters to reveal a raft of 8s and 9s. Importantly, a substantial proportion – roughly two in five – did not reach what has become the critical benchmark of attainment: grade 4 or above in both English and maths. These young people should be of concern to education policy makers because they are most at risk of not making a successful transition to further education, training or employment. Our working paper, published last week, explores what happens to these young people after Key Stage 4. It highlights the need for more joined-up policy making across the 16-18 phase to enable all young people to progress.

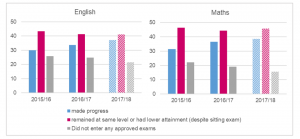

One of the key findings is the fact that, although almost all young people without a 4 in English and maths are obliged to continue studying these subjects until age 18, only about a fifth of them achieve the elusive grade 4 during these additional two years of study (based on figures for 2017). Not only this, the majority of this cohort did not improve on their attainment at Key Stage 4, but instead remained at the same level or reached a lower level of attainment than they did at age 16. Provisional figures for this academic year released a few days ago suggest that there has been an increase in the proportion of learners improving their attainment in both English and maths. This is driven partly by more people being entered for exams, and partly by the fact that, among those sitting exams, the proportion who attain a higher level of learning has increased (see figure 1). This is good news. But it remains the case that the majority of young people do not make progress in English and maths despite continuing these subjects for a further two years after Key Stage 4.

Figure 1: Percentage of learners who made progress, did not make progress, and did not sit approved exams in English and maths during the 16-18 phase, 2016 to 2018

Source: Author’s calculations based on Department for Education SFR05/2017: A level and other 16-18 results (revised): 2015/16 – English and maths tables: table 15a and 15b, Department for Education. SFR 03/2018: A level and other 16-18 results (revised): 2016/17 – English and maths tables: table 13a and 13b, and Department for Education: A level and other 16 to 18 results: 2017 to 2018 (provisional) – English and maths tables: table 13a and 13b. Please note that figures for 2018 are provisional.

Our analysis also looked at where young people without a grade 4/C in both English and maths go once they’ve completed their GCSEs. Worryingly, our analysis found that a relatively large proportion of young people who do not achieve the 9-4 English and maths benchmark – about 10% – fail to make a sustained transition to further education, employment or training.

These data tend to set off a ‘blame game’. Some blame schools for having ‘failed’ to get young people to the expected level, typically resulting in even more focus on English and maths and on preparing for exams. Others blame post-16 providers for ‘failing’ to get students over the line. Very little attention seems to be focused on understanding the circumstances of young people who haven’t achieved academic success in these subjects at 16 or why, or on making sure that there is high-quality appropriate provision to enable all of them to develop their talents and potential in the post-16 phase. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) recently showed, spending-per-student in further education colleges and sixth form colleges has fallen by around 12% in real terms since 2011/12, and funding for school sixth forms has fallen even more steeply. The current government’s attempt to reform post-16 vocational education by positioning the T Levels as alternatives to the A levels is unlikely to be an immediate answer for many of the young people described here. At the same time, apprenticeship is a largely post-19 pathway with places for 16-18 year olds constituting around one fifth of the total.

Informing policy

To inform future policy developments, our ongoing work will be examining the trajectories of GCSE lower attainers in more detail: which types of learners make progress in English and maths during the 16-18 phase and which do not; whether different types of learners do better in different types of post-16 institutions; and how far the different access arrangements at a local level are having an impact on which pathways young people can follow.

The lack of progress that so many young people make between 16 and 18 is a real problem in a country increasingly concerned both with raising productivity and tackling long standing problems of social and spatial exclusion. By learning more about the characteristics and experiences of learners with ‘below expected’ attainment we aim to provide a better evidence base for designing national and local support measures to enable young people to reach their potential and avoid falling further behind.

We make the following recommendations:

- assigning blame must end;

- policymakers need to use a robust evidence base to understand and address the barriers that impact ‘lower attainers’;

- rather than focusing only on new technical alternatives to A levels, the government should ensure appropriate, high-quality post-16 provision for all young people, including those with lower GCSE attainment.

Note: The working paper is part of a wider project exploring the post-16 transitions of those who do not achieve grades 9-4 in English and maths. This project is funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation.