Shelter says there is a housing crisis, while the Bank of England fears an unsustainable property price bubble is underway. But, as Dr Nissa Finney explains, the housing crisis hits ethnic minorities worst.

The UK is in a housing crisis, according to Shelter. This has been brought about by the shortage of housing coupled with rising costs of mortgages and rents. The housing crisis has received much attention from media and government, but relatively little attention has been paid to who, exactly, is in the most precarious housing situations.

The Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity’s (CoDE) analysis of 2011 Census data shows that Black and Asian ethnic groups are more likely to be in insecure and overcrowded housing compared to other ethnic groups, including White British.

Although the preference for home ownership is common across ethnic groups, some minority groups are over-represented in insecure private rented accommodation. Private renting was highest in 2011 for the Other White and Arab ethnic groups. Over half the population of these groups in England and Wales lives in private rented housing. By comparison, 15% of Black Caribbean and White British ethnic groups live in private renting.

These ethnic inequalities are even more pronounced for young adults. In 2011, a third of people aged 25 to 34 in Black Caribbean and Bangladeshi ethnic groups lived in private renting compared to three quarters of Other White young adults.

High levels of private renting are found in London, but not only in London and large cities. For example, a large proportion of Indians living along the south coast of England are in privately rented accommodation. Private renting is the experience of the majority of the Other White ethnic group in North Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and mid Wales.

For some ethnic groups, private renting is not a London experience. For example, for the Caribbean group, proportions in private renting are relatively low in London compared to elsewhere, such as the north east of England.

Ethnic differences in levels of private renting are concerning from the point of view of equality. This is because they suggest people from some ethnic groups can more easily get the housing they aspire to than others. What is more concerning, though, is that these inequalities are getting worse. This is clearly shown by CoDE’s analysis of the last three censuses.

All ethnic groups have higher levels of private renting in 2011 than in 1991. But private renting has increased particularly dramatically for some ethnic groups. The increase in private renting between 1991 and 2011 was proportionately greatest for the Indian, Pakistani and Black Caribbean populations, for whom the percentage in private renting more than doubled.

For example, in 1991 8% of the Indian ethnic group lived in private rented housing; by 2011 it was 24%.

The rise in private renting has been accompanied by a decrease in home ownership. Since the early 1990s levels of home ownership have decreased for all ethnic groups. However, this fall in home ownership was proportionately greatest for the Pakistani (-18%), Chinese (-17%) and Indian (-16%) groups, meaning they have become more exposed to housing insecurity over the last two decades.

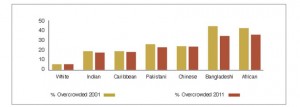

The housing crisis is also about housing conditions such as overcrowding. Black and Asian groups are most likely to live in overcrowded accommodation (Figure 1). While 6% of White British households are overcrowded, a third of Black African and Bangladeshi ethnic groups live in overcrowded households.

There are also ethnic differences in who lives in spacious housing. Three times as many White Britons as Black Africans and Bangladeshis live in houses with two or more spare bedrooms.

The persistence of ethnic inequalities in the housing sector suggests that this has been an area of policy neglect. Why is it that people from some ethnic groups are more likely than others to live as they would like to? And what might be done about this?

Part of the explanation for ethnic differences is to do with immigration history. The high level of private renting for the White Other group, for example, is likely to be because they are a recent migrant group with a young age structure for whom the private rented sector provides easily accessible and flexible housing. However, the extremely high levels of renting may also mean the White Other ethnic group is particularly at risk of housing insecurity and rental price rises in a precarious housing sector.

The fact that the housing crisis is hitting more established Black and Asian minority groups particularly hard no doubt has a lot to do with broader socio-economic ethnic inequalities. Why these inequalities persist is a question at the heart of CoDE’s work.

And we must not rule out the potential role of discrimination, as suggested by a BBC investigation in 2013.

Given that satisfaction in housing is related to overall life satisfaction, wellbeing and physical and mental health, it seems it is time to pay due attention to who is most vulnerable in today’s housing crisis, why that is and what might be done about it.

Figure 1: Percentage of ethnic group in overcrowded accommodation, 2001-2011

Source: Census 2011

Further reading

- CoDE Census Briefing by N. Finney and B. Harries (2013) ‘How has the rise in private renting disproportionately affected some ethnic groups?’, Dynamics of Diversity: Evidence from the 2011 Census.

- N. Finney and B. Harries (2013) ‘Understanding ethnic inequalities in housing: Analysis of the 2011 Census’ Better Housing Briefing 23.

[…] Original source – Manchester Policy Blogs […]