Professor Diane Coyle and Dr Marianne Sensier have recently conducted research comparing transport infrastructure projects that have used HM Treasury’s Green Book. In this blog they argue that this methodology, alongside political prioritisation of projects in and around London, has reinforced existing success in wealthy, already highly productive parts of the UK. Future infrastructure investment needs to be based on a strategic view about economic development for the whole of the UK, which the UK Government now accepts in its pledge to ‘level up’ other regions.

- The productivity gap has widened between London and other regions.

- Transport infrastructure investment is skewed towards London and the formal appraisal methodology has not been applied consistently to other regions.

- The Northern Rail upgrade and schemes that were cancelled in 2017 by the Department of Transport were, according to the National Audit Office, due to the benefit cost ratios (BCRs) being revised down as costs increased with central government delays and procurement failures.

- To correct the bias we need a long-term strategic view for the UK economy. Greater productivity in all places will improve national productivity with better social outcomes and lower inequalities between and within regions.

Cost-benefit analysis vs political bias

Living standards and productivity are affected by many variables, and there is a large literature on the possible explanations for the UK’s regional imbalance; patterns of infrastructure spending are only one possible contributory factor. However, the OECD has observed that the UK has been spending less on infrastructure than its other member economies for some decades, and also that its perceived quality was lower than in the other G7 countries. However, transport appraisal methodology in the UK favours the capital as it includes the “wider” benefits of agglomeration impacts, dependent development and more productive jobs. Investment in the future is determined by past success, giving rise to the “Matthew Effect”, whereby further infrastructure investment occurs in places that are already successful. This can change, however, if decisions about significant investments explicitly incorporate a strategic view about economic development for the whole of the UK, as the economic theory underpinning cost-benefit analysis (CBA) implies should be the case. Rather than only investing in already highly productive places, this would enable public infrastructure investment to reflect the government’s strategic view about potential productivity gains – potential that government actions could themselves help realise, given the self-fulfilling character of some policies.

There are wide regional economic disparities in the UK between productivity per head in London and other English regions along with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This gap has grown over time and even for the South East has doubled in two decades. The share of real gross value added earned by London has increased from 19.9% of the UK total (excluding Extra-Regio) in 1998 to a 24% share in 2017, when the share of jobs in the capital has increased from 14.8% in 1998 to 16.6% in 2017.

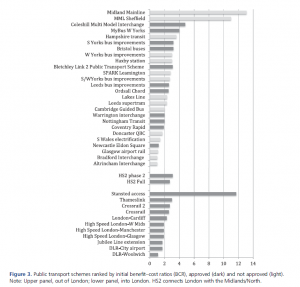

Figure 3 from the paper shows that for a range of major public transport schemes relatively low BCRs for schemes serving London (less than 2) have routinely been approved, whereas outside London there is a more mixed picture. Some projects with far higher BCRs in the English regions have not been approved. This is highly suggestive of political input to the allocation of funds.

The need for dynamic planning

The Eddington review of transport infrastructure in 2006 forcefully recommended concentrating scarce investment funds in places where transport constraints have significant potential to hold back economic growth, particularly in London where it argued congestion should be alleviated so the agglomeration can continue. Although externalities such as getting people off the roads and reducing emissions in train schemes are taken into account in official CBA, there is no scope for analysis of the limits of agglomeration. For example, a Transport for London Cross-rail 2 report predicts that by 2030 there will be 10 million people living in London, up from 8.6 million in 2018. But has London reached a tipping point and will further densification and transport spending really help growth?

The failure to incorporate dynamic change in the economy is key to the issue of regional skew, trapping investment decisions in past geographic distribution of growth. Average commuting time has stayed at around 1 hour since the 1970s so improving transport connectivity into London is improving the opportunities for those living around London to work there, and also pulling people out of other areas.

Another factor that has increased regional disparities is the loss of rail connectivity from the ‘Beeching Axe’ cuts to the UK’s rail network in the 1960s. The closures affected little used and unprofitable lines. However, research shows that, even conditioned on the decline of affected areas before the Beeching report, the closures accelerated the population decline, and the proportion of skilled and young workers in the population.

Infrastructure planning post-Brexit

There is evidence to suggest that improvements in intra-city networks first are necessary before improvements to inter-city links. For example improving the rolling stock and timetable reliability associated with the Northern service throughout Greater Manchester should be the first step before building a high-speed line connecting Manchester and Leeds, as the within city networks need to be able to cope with large amounts of commuters travelling within and between cities.

The 2018 revisions to The Green Book, the Rebalancing Toolkit and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2017) Industrial Strategy White Paper and its subsequent implementation through local industrial strategies perhaps indicate dawning recognition at the centre of government that a different spatial distribution of economic activity around the UK is desirable and may be possible. Indeed, it may be politically essential in the context of the politics of devolution in the UK and trends in voting patterns particularly in the light of Brexit and the 2019 General Election result. The Industrial Strategy Commission (2017) said “further and faster devolution” to cities and regions would be essential to raise national productivity levels. It is vital that the Government supports investment in all regions in order to improve regional and national productivity and to keep its promise to the “Workington Man” and the “Teesside Tories”. The next Green Book revision needs to include a new strategic view of the location of economic activity and accept the fact that it is shaped by policy choices. This includes improving transport infrastructure within and between regions across the country.

The analysis in this blog is based on Professor Diane Coyle and Dr Marianne Sensier’s article, “The Imperial Treasury: appraisal methodology and regional economic performance in the UK”, published in Regional Studies in 2019.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.