As we celebrate World Water day, Dr Timothy Foster, Lecturer in Water-Food Security in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, and Dr Roshan Adhikari, Research Associate in the Global Development Institute, take a look at how rainfall variability impacts farmers in South Asia and explore what local and national governments can be doing to boost resilience and lift farmers out of poverty.

- An estimated 60% of rural households in South Asia depend on agriculture for their main source of income and livelihood.

- Irrigation helps farmers to protect against crop failures caused by rainfall variability, but access for many farmers is constrained by large investment and fuel costs.

- Opportunities exist to make existing irrigation systems work better and more effectively for farmers, including through targeted support for purchasing and maintaining fuel efficient irrigation pumps.

- Upscaling requires international donors and national governments to think holistically about how to use both new and existing technologies to deliver sustainable and equitable access to irrigation in South Asia.

Smallholder farmers underpin the food security and economies of countries across South Asia. It is estimated that around 60% of rural households in the region depend on agriculture for their main source of income and livelihood. Decreasing vulnerability of smallholder agriculture to weather shocks, which are expected to be exacerbated by climate change, therefore is a key component of national government and international donor initiatives to tackle food insecurity and rural poverty across the region.

Importance of groundwater irrigation in South Asia

One of the most important weather-related causes of crop failures and low agricultural productivity in South Asia is drought and monsoonal rainfall variability. While the U.N. SDG6 (‘Clean water and sanitation‘) has heavily emphasized the importance of water supply for domestic uses, water is equally important for agriculture. Irrigation helps farmers to protect their crops against drought risks, leading to higher and more stable crop yields and enabling farmers to cultivate their land year-round even during the dry season. Groundwater is a key source of water for irrigation in South Asia. However, access to cost-effective, reliable and adequate groundwater supplies is not consistent across the region. In the western Indo-Gangetic Plains (NW India and Pakistan), farmers historically have benefited from widespread rural electrification and subsidisation of electricity costs, greatly reducing costs of pumping groundwater for irrigation purposes. However, in the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains (including Nepal, eastern India and Bangladesh) farmers remain largely dependent on unsubsidised diesel-powered pump irrigation systems.

‘Dirty diesel’ or a profitable technology for farmers?

The high costs of operating diesel pump irrigation systems, along with a view that these systems are dirty and polluting, have been widely cited as a key factor constraining agricultural intensification in the region. Replacing diesel pumps with cheaper and cleaner irrigation systems based on electric or solar power has therefore been the subject of wide ranging proposals by governments, donors and researchers over recent years. Yet, scaling these solutions in countries within the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains has significant challenges in the short- to medium-term future. Electric pumps require large capital investments in grid infrastructure to bring power lines to rural fields, whereas solar pumps at present face large technical and financial constraints due to high purchase costs and structure of rural landholdings. This raises several important questions for scientists and policymakers: Are we neglecting opportunities to make existing diesel pump systems more cost-effective for farmers? If so, could these deliver quick poverty reductions while supporting transition to future low-carbon systems?

How can we make diesel pump systems more profitable and productive?

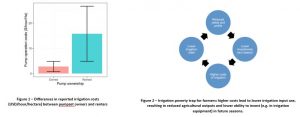

To answer these questions, we have been working with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) in South Asia over the past year to collect data from farmers in the Terai region of Nepal about the characteristics and costs of diesel-pump irrigation systems in the region. Our work has shown that there are huge disparities in how much individual farmers must pay to access groundwater for irrigation, ranging from as little as $5/ha to $200/ha for each irrigation. The highest costs are borne by those farmers that depend on renting pumpsets for irrigation (Figure 1), who typically represent the poorest and most marginalised households that have limited capital resources or little access to credit. Pump selection is also found to be a key determinant of irrigation costs, with many farmers continuing to operate large Indian-made pumps despite the fact that these pumps are costly to operate and purchase relative to smaller, lower cost models manufactured in China.

Contrary to common assumptions, these cost variations have important implications for how farmers use irrigation and how resilient they are to climate shocks. When irrigation costs less, we find that farmers irrigate their crops more often and are less exposed to risks posed by drought and year-to-year uncertainty in the timing of the monsoon onset. This intensification of irrigation has been shown to improve agricultural productivity, with higher crop yields helping to reduce frequency of food insecurity and boost incomes of rural households. In contrast, farmers faced with high irrigation costs are trapped in a cycle of poverty (Figure 2).

Holistic solutions to achieve irrigation intensification

We argue that international donors (both governmental – e.g. the UK Department for International Development – and private – e.g. the Gates Foundation) and national governments in South Asia should think holistically to leverage complementary solutions to enable expansion access to irrigation in South Asia and other regions where the diesel pump is de-facto technology used by farmers. Our research suggests that while diesel-pump irrigation is still a ‘second-best’ solution, there are ways of adapting these existing systems to make them both productive and profitable for farmers. Key policy priorities should be enhanced financial support, for example through subsidies or credit systems, to enable pumpset purchasing by poor water-insecure households. Furthermore, on-the-ground engagement is needed to promote and support alternative fuel-efficient pumpset designs. Low-cost portable Chinese pumps, for example, seem to fulfil several key needs of farmers, but adoption remains slow due to limited availability of maintenance services, spare parts and a lack of appropriate standard and quality control within supply chains.

Near-term improvements in performance of diesel-pump irrigation systems can also have the added benefit of reducing reliance on these systems in the medium- to long-term future. Farmers who have higher incomes and are less exposed to production risks in the present are likely to be more able and willing to invest in new irrigation technologies (e.g. solar) and other productivity-enhancing farming practices. Such changes would contribute massively to reducing poverty and food insecurity in presently impoverished and water-insecure parts of South Asia. However, long-term shifts to renewable pump technologies must also consider risks to groundwater sustainability posed by large reductions in the cost of irrigation pumping. While groundwater resources are currently under exploited in the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains, aquifer depletion trends elsewhere in the region highlight the need for early development of effective institutions and policies to manage groundwater use within sustainable limits.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.