Within the Greater Manchester region, the highest paid roles are typically dominated by men. In this blog, Anna Sanders and Professor Francesca Gains break down the gender ratios within several key sectors, and offer solutions to increase gender parity across the region.

- Men are concentrated in higher-paid occupational sectors. Two-thirds of managers, directors and senior officials in Greater Manchester are men. Skilled trades and process, plant and machine operatives are also heavily male-dominated sectors.

- Women have traditionally been more likely than men to work in administrative and secretarial positions. The proportion of women working in such positions in Greater Manchester has decreased over time, but still remains high in comparison to men.

- Policy action to address these inequalities should encourage women to enter occupational sectors in which they are currently underrepresented. At the same time, attempts should be made to attract more men into occupational sectors in which they remain underrepresented.

Two key recent reports have highlighted trends in the Greater Manchester employment market. The Independent Prosperity Review highlights areas to boost productivity and increase prosperity across the region. Meanwhile, the Resolution Foundation’s Low Pay in Greater Manchester report provides an in-depth insight into Greater Manchester’s low-paid workforce. While both reports provide an invaluable insight into the Greater Manchester employment market, they lack a specific gender focus on occupational structure. More could be said about the gendered patterns of Greater Manchester’s labour market and its impact on prosperity and productivity.

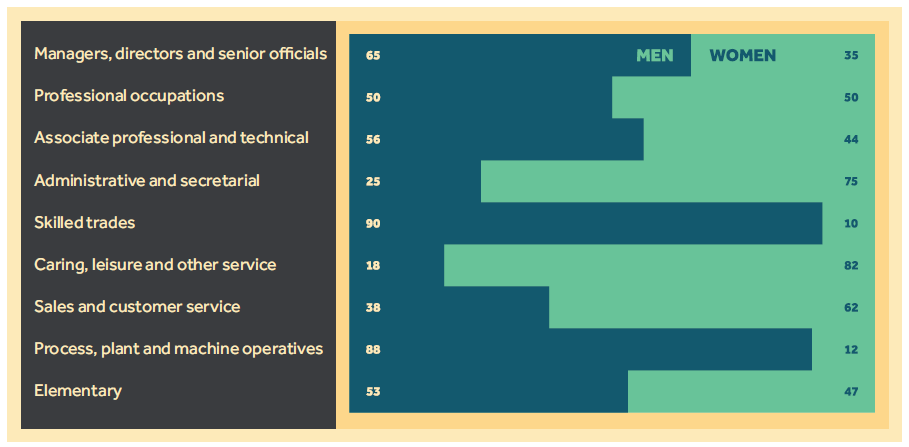

Figure 1 represents occupational breakdown by sex in Greater Manchester for 2018. Men are concentrated in higher-paid occupational sectors. Two-thirds of managers, directors and senior officials in Greater Manchester are men. Skilled trades and process, plant and machine operatives are also heavily male-dominated sectors. At the same time, Figure 1 shows that women continue to be overrepresented in traditionally domestic and ‘feminised’ sectors, outnumbering men in caring, leisure and other service occupations by four to one. These sectors are often low-paid, particularly in Greater Manchester: around one in five (19%) of employee jobs in health and social care in Greater Manchester are low-paid (compared to the national figure of 10%). The Resolution Foundation reports that women comprise the majority of those in low-paid employment in Greater Manchester (58% vs 48% of non low-paid employees).

Figure 1. Occupational breakdown by sex in Greater Manchester (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Looking at Greater Manchester overall may mask variation between local authorities. Within the Annual Population Survey, it is not possible to break the data down further by each local authority. However, we can compare occupational patterns in Greater Manchester to the UK average. The picture in Greater Manchester is broadly similar to that of the UK at large (Figure 2), and shows that the concentration of men and women in traditionally ‘gendered’ occupations is widespread.

Figure 2. Occupational breakdown by sex, UK rate (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Changes over time

Women have traditionally been more likely than men to work in administrative and secretarial positions. The proportion of women working in such positions in Greater Manchester has decreased over time, but still remains high in comparison to men. In 2004, around 23% of female employees held administrative and secretarial positions, compared to just 6% of male employees. By 2018, around 17% of female employees were employed in the administrative and secretarial sector, compared to 5% of male employees.

Similarly, while the share of male employees working in skilled trade occupations in Greater Manchester has decreased over time, men continue to be overrepresented in this sector. Approximately 20% of male employees worked in skilled trade occupations in 2004, compared to just 2% of female employees. The poor representation of women in this sector has remained stagnant, with 2% of female employees working in skilled trades occupations in 2018. By 2018, 16% of male employees held roles in skilled trade occupations. Such decline is partly due to net job losses – particularly among male employees – in skilled trade occupations after the 2008 financial crisis. Additionally, research by the Resolution Foundation finds that the decline is also linked to fewer younger workers entering skilled trade industries.

Finally, the share of female employees working in caring occupations increased after the onset of the recession. Following the financial crisis and growing demand on care services, the sector has witnessed growing casualisation, leading to increased job insecurity. In 2014, the Burstow Commission estimated that, nationally, 60% of the home care workforce was on zero-hours contracts. The national picture is likely to be replicated in Greater Manchester, with implications for women’s employment conditions and job security, since they comprise the majority of those in the caring sector.

Key messages

Occupational segregation persists. Sylvia Walby and Wendy Olsen’s national report points out that occupational segregation limits women’s potential in the labour market, and has implications for productivity. Policy action to address these inequalities should encourage women to enter occupational sectors in which they are currently underrepresented, such as process, plant and machine occupations, or skilled trade occupations. At the same time, attempts should be made to attract more men into occupational sectors in which they remain underrepresented, such as caring and leisure services, or administrative roles. Policymakers should work with local employers, schools, and further education providers to open up apprenticeships and job opportunities for school children and young men and women.

Additionally, policymakers should work with public and private sectors in the region to address the precarious employment circumstances of women (and men) in occupations in the foundational economy and social infrastructure.

This article was originally published in On Gender, a collection of essays providing analysis and ideas on taking a gendered lens to policy in Greater Manchester and devolved regions across the UK. You can read the full publication here.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.