Many workers in the nuclear industry are poised to retire – just as a major new nuclear building programme gets underway. Professor Andrew Gale and Professor Nawal Prinja consider the implications.

The nuclear industry is facing a severe skills and technology management shortfall. Five new stations – Oldbury, Sizewell, Moorside, Wylfa and Hinkley – are planned. These will require 110,000 to 140,000 full-time equivalent person years. This coincides with a period when many existing nuclear workers, particularly experienced managers, are nearing retirement.

According to the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board chief executive David Edwards: “The UK nuclear sector currently employs around 44,000 people and this figure is set to soar as decommissioning projects and nuclear new build come to fruition. The new build programme is anticipated to create 30,000 new jobs over the next 15 years.”

Edwards explains that the nuclear construction sector needs to recruit 60,000 people in the next decade. He predicts this recruitment will be required across all levels and will be evenly split between graduates, apprentices and migration from other industry sectors.

Some of the demand will be met from workers with nuclear experience in the defence sector and nuclear decommissioning – with a potentially damaging impact on decommissioning activity. But these likely recruits may not have the integrated technology management skills required for the modern, efficient nuclear workforce of the future.

A recent HEFCE report indicates a big increase in students accepted on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses. In 2013/14, 98,000 students were accepted on STEM undergraduate courses, the highest number ever recorded – an 8% rise on the previous year and an 18% increase on 2002/03.

However, further and higher education provision in the UK is fragmented and over-competitive. It fails to provide a vertical pipeline of skills that meet the needs of the industry. While Manchester and other universities have Doctoral Training Centres that focus on nuclear science, they are concerned with research and development, not much-needed nuclear technology management education. Meanwhile, support for EngD postgraduate research training has been cut.

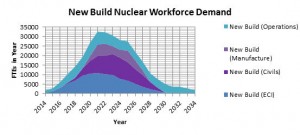

The Nuclear Workforce Model (Figure 1), produced by Cogent on behalf of the Nuclear Energy Skills Alliance, indicates predicted pinch points in demand. This shows workforce demand over a 20 year period to 2034, with a peak for off-site work around 2021 and a peak mainly driven by on-site activity in 2025.

Figure 1. Source: Bennett, Cogent (2015)

The Cogent Next Generation report contains detailed predictions on the likely skills shortages. These are in design and planning, including project management; equipment manufacture, with a need for design and manufacturing engineers; engineering construction, requiring planners and non-destructive testing engineers; commissioning, operations and maintenance, requiring project management, engineering design and technical and scientific skills; and general nuclear work, requiring project management skills.

This demand for planners and project management capability will almost certainly have to be imported from overseas during the next ten years, as supply will not be able to meet demand.

In answer to the current and projected need, The University of Manchester provides blended learning in generic project management education through a unique industry-led modular programme (MSc Project Management Professional Development Programme). Many of the students are from the nuclear sector and benefit from the flexible and tailored model upon which the new MSc Nuclear Technology Management Professional Development Programme (Nuclear-PDP), a European first in offering a full management-focused course, has been built.

To strengthen and build on such initiatives, the higher education sector needs to be strongly encouraged by Government and industry to work together with further education providers and fellow higher education institutions to provide a comprehensive and flexible learning package that ranges from apprentice education and training through to foundation degrees, honours degrees, postgraduate taught programmes and part-time doctoral training. This provision needs to be backed by Continuing Professional Development at all levels.

The emphasis must now be on integration of skills development both vertically (in levels) and horizontally (in terms of inter-disciplinarity). The Government’s initiative of the National College for Nuclear will hopefully prove a positive contribution.

But universities must focus much more on their collaboration with industry. An Ernst and Young report argues that universities will not survive under their current business model and must change. Liaising with the nuclear industry has been key to the success of Manchester’s Nuclear-PDP.

In addition, immigration policy must meet the needs of UK industry. As the CBI’s director for employment and skills, Neil Carberry, has said: “Employers need a system which doesn’t just control migration but attracts the skilled workers the economy needs, who would otherwise go to our competitors.”

The retirement of nearly 70 per cent of the management of the nuclear sector is a serious cause for concern. It is not just a loss of human resource, but also of the tacit knowledge, experience and anchors for the UK’s nuclear culture. These are essential for a vibrant industry and successful new nuclear fleet. Momentum needs to be garnered and maintained to focus on fresh thinking and ideas about how to address the nuclear industry’s projected skills deficit to take us into a successful future.