The need to build back better has received widespread endorsement, not only because the COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for change but also because it has revealed the high price paid by those facing inequality in the labour market, including inequality by gender. Here, Professor Jill Rubery, Director of the Work and Equalities Institute, discusses the importance of building gender equality into recovery plans from the COVID-19 pandemic.

- New research has shown that women’s mental ill-health has risen more steeply than men’s during the pandemic.

- Entering unemployment has the worst effect on people’s mental health, over furlough or a reduction in hours.

- Work sharing or short-time work offers an alternative approach where all employees reduce their hours to protect more jobs.

- This approach, alongside complementary policies, could help preserve mental health and wellbeing and support a more gender equal sharing of work and care.

Progress on gender equality may be reversed in the recovery from COVID-19 unless action is taken. Women have been more at risk of both job loss and furlough and the move away from furlough may rapidly increase the risk of job loss as employers can now determine not only if it is safe to return to work but also whether parents can be required to return even before the opening of schools and many nurseries. Indeed, despite the surprisingly successful teleworking experiment, the current message is to return to the prior normality. This is a missed opportunity to build on positive developments under the COVID-19 pandemic and to fix the gaps in the support systems for gender equality, some evident before COVID-19 and others emerging during or because of the crisis. While women may have been in the forefront of the key workers being clapped during lockdown, little is being done to improve their pay and conditions. Care workers with COVID-19 symptoms will still have to choose between surviving on around £95 a week statutory sick pay, one of the lowest in Europe, or risking their own and their clients’ lives by continuing to work.

Changes to employment status resulting in mental ill-health

Building gender equality into the path to recovery has many benefits, not only reducing the risk of wasting the talents of half the population but also of reducing risks of both adult and child poverty.

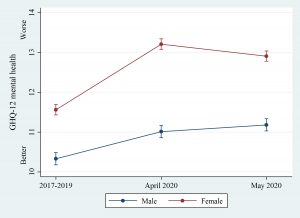

Yet another really important reason to focus on gender equality is to limit the risk of mental ill-health. A new analysis based on data for April and May 2020 from the Understanding Society survey (analysis by researchers from Cambridge, Salford, Leeds and Manchester) has found that although both men’s and women’s mental health worsened during the COVID-19 crisis, see Figure 1 it was women’s ill-health that rose most steeply. Moreover, for both sexes it was entering unemployment that had the worst impact on mental health of all the various options during the COVID-19 crisis – even worse than furlough or reduced hours of work. This indicates that mass redundancies could result in permanent damage to the mental health of the population.

Figure 1. Mental health rates for men and women in 2017-2019, April 2020 and May 2020 waves of Understanding Society

Source: Understanding Society COVID-19 Study

So is there an alternative? These experiences point the way to an alternative policy agenda that could reduce the risks of high unemployment and further deterioration in mental health while also promoting gender equality.

Reducing unemployment and promoting gender equality

To seriously reduce the risk of high unemployment and maximise job retention we need to use work sharing (or short-time work) across the whole workforce. Although those on furlough can start to work part-time from August the risk of redundancies would decrease if, in sectors and companies operating below capacity, all staff were, for example, to be put on the equivalent of a four-day week, including those who were kept on normal hours during lockdown. Short-time work is used in other countries and provides a more equitable route back to normal working, reducing the tendency to select people for redundancy just because they were on furlough. Companies using work sharing to preserve jobs could receive subsidies, perhaps enabling a higher level of earnings to be maintained. This would be much less costly than the furlough scheme while keeping more people active and attached to jobs, with all the benefits to mental health and wellbeing this provides.

This policy of work sharing could have a double benefit; not only would it enable a smoother and less risky transition out of furlough but it could also set the foundation for changing the gender division of labour across both paid and unpaid work. These dual benefits need to be recognised and promoted, perhaps through the aim to move to a maximum 30 hours of wage work per week. Without such a common objective there is a danger of reinforcing gender divides if in the future women’s jobs are organised as telework while men return to their offices. The COVID-19-induced experimental integration of work and care, often for both parents, has increased men’s engagement in childcare even if women have carried the main additional burden. To sustain work sharing across all groups, minimum hourly pay would need to rise, but this could have the positive spin-offs of improving pay for key workers, including care staff and boosting women’s relative pay in many households, in line with a more equal sharing.

Beyond work sharing

Work sharing will be ineffective where demand is low or where much of the work is part-time. It is necessary to complement this approach with job creation schemes and opportunities for retraining, but the current build, build, build agenda is too focused on the construction sector and by implication men’s jobs. Instead of only roads, we need to focus on rebuilding our damaged nursery sector and our elder care system.

Just as in Roosevelt’s New Deal, we also need to complement the demand-side policies with action to strengthen workers’ rights and plug the holes in the system of worker protection in the UK that have been revealed by COVID-19. Three holes particularly need filling:

- The first is to improve the very low statutory sick pay in the UK, lower than anywhere else in Europe bar Malta, resulting in by far the highest reliance on voluntary employer top-ups to statutory sick pay. In any second wave, it will still be women facing higher risks of infection and the dilemma of whether to follow the track, trace and isolate policy, and only 43% of employees in the care, leisure and other services sector receive above statutory sick pay.

- This problem is exacerbated by the second problem. That is the high number of employees – estimated by the TUC to be 2 million and 70% of them women – who do not even qualify for statutory sick pay or indeed unemployment benefits, namely those who do not regularly earn over £118 a week due to short hours, low pay or irregular employment such as zero hours contracts.

- The third hole in the protective floor is the lack of security for parents who end up having to care for children under local lockdowns or school closures. They may only be given unpaid leave for a period that it is up to the employer to determine as reasonable. Moreover, if childcare proves problematic due to the collapse of after school care, private nurseries or summer holiday camps, or frequent school closures, there is an increased risk that the share of women being made redundant or being forced to quit may rise still further.

Without new policies and protections, the danger is not only that we miss out on this opportunity for radical change but that we slip backwards into greater gender inequality, household insecurity and poorer mental health.

Take a look at our other blogs exploring issues relating to the coronavirus outbreak.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.