From June, Greater Manchester will get an interim mayor as part of a deal with the Government on regional devolution. But its imposition without a referendum is a fundamental error by the political elite that may well backfire, argues Professor Colin Talbot.

‘Mayors’ seem to have become the default answer of many in the political elite to the problems of local government and governance in the UK, or more specifically England.

Linked to the idea of English devolution as an answer to Scottish ‘home rule’ this has become a heady brew. But maybe it’s time to ask some sober questions about this project of ‘Devo Manc’, at least in terms of the proposed system of government for Manchester.

My argument is, simply put:

- elected mayors are based on assumptions about what Archie Brown has called ‘the myth of the strong leader’;

- they are a ‘presidential’ style of government that is ill-suited to our ‘parliamentary’ political tradition, especially at local government level;

- in Manchester specifically it risks undermining the delicate balance that has been so successful with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority;

- its’ imposition without a referendum is a fundamental error by the political elite that may well backfire.

The Myth of the Strong Leader

The first and most important idea underpinning the whole movement towards Mayors, Commissioners and the like is what Archie Brown memorably calls ‘the myth of the strong leader’.

Brown’s main argument is that such concentration of power in a democracy is antithetical to democratic norms of dispersal of power and checks and balances. He points out that even in autocratic systems, collective leaderships tend to fare better than single person dictatorships.

Brown also argues that the idea that a single leader can have the ability, or time, to properly consider a wide range of policy issues is obviously false and impractical. In reality what tends to happen in such leader-centered systems is that she/he has to delegate to unelected deputies who speak on her/his behalf, with all sorts of problematic consequences.

There is also a tendency towards hubristic behavior in any system that is built on the assumption that one person has all the answers. In their recent book ‘The Blunders of Our Governments’ Anthony King and Ivor Crewe analyse 12 major ‘cock-ups’. Going through their conclusions there are three near universal factors that apply to all the cases:

- a lack of ‘deliberation’ in decision-making, in other words decisions usually made in haste by a single person or small group (all 12 cases) – this is also often linked to the development of ‘group-think’ in the decision-making coterie (8 cases).

- the absence of any serious Ministerial accountability for their decisions (12), meaning that few Ministers ever stay around long enough to be held accountable for policies they enacted;

- and the weakness of Parliament in pre-scrutiny of policies – although legislation is now subject to pre-scrutiny, policies as such are not subjected to thorough examination usually until well after they have been implemented (and disaster has struck). Even when Parliament does try to scrutinise things in advance, it has few resources and almost zero power to prevent ‘blunders’ happening.

Of these three reasons, the first and third especially apply to ‘presidentialist’ systems of Mayors or Police and Crime Commissioners.

‘Presidentialism’ in Local Government

Britain, as we all know, is a parliamentary democracy. But ‘parliament’ does not just apply the Palace of Westminster – the devolved governments and local government too are ‘parliamentary’ in form: that is they are made up of elected representatives who appoint an executive of some sort.

Indeed, I would argue that local government was, until quite recently, more ‘parliamentary’ than central government. In the old, pre-cabinet, form of local government ‘the Council’ was the executive. Decisions were taken through Committees representing all political sides in the Council – so it would be rather like the Select Committees in Parliament actually running their respective departments of state.

This system has been drifting in a more autonomous executive direction for some time. First, in the 1970s and 80s the role of Committee chairs were strengthened and the powers of Council Leaders and Council Chief Executives grew.

Then in the Local Government Act 2000 the idea of a Leader and Cabinet system was introduced, with committees reduced to the role ‘scrutiny’. The final step in this evolution towards executive presidentialism is the attempt to create directly elected Mayors (Police and Crime Commissioners is a parallel change in the same direction).

What is fascinating about this evolution – and especially most of the academic analysis (and in some cases advocacy) of it has been the degree to which it has ignored wider debates about presidential versus parliamentary forms of government. The predominant view amongst political scientists studying national forms of government has long been that parliamentary forms of government are inherently more stable and produce better results than presidential ones. With the major exception of the USA, presidential forms have a much greater tendency to degenerate into autocracies or dictatorships.

There are then two objections to ‘mayoral’ forms from this perspective: first, that such a ‘presidential’ form is inherently weaker and less preferable than the old ‘parliamentary’ forms of local government; and secondly that grafting such a ‘presidential’ model onto the root stock of parliamentarism in the UK is bound to cause all sorts of problems.

Why A Mayor for Greater Manchester?

Since the abolition, by Margaret Thatcher, of the metropolitan councils (in London, Manchester, Birmingham and others) in the 1980s, Manchester has been hailed as having managed to create the necessary conurbation-wide forms of governance and collaboration. This culminated in the formation of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, on a voluntary basis, bringing together in collaboration the ten local authorities that make up Greater Manchester.

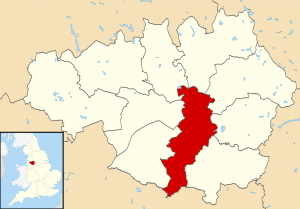

One of the reasons this worked so well is a simple matter of political geography – Manchester City Council (the one in red below) is roughly the same size as the other 9 councils and this equality of size makes for easier relationships.

[Source: Wikipedia]

Compare this to Birmingham, where the City Council is much bigger than its neighbours and conurbation-wide collaboration has been markedly more difficult.

[Source: Wikipedia]

The success of greater Manchester isn’t just down to political geography, but also to the way in which the leaderships of the 10 local councils have managed, despite major political differences (and the usual rivalries), to work together.

The imposition of a directly elected greater Manchester mayor risks unsettling this delicate balance. A GM Mayor will almost certainly always be a Labour Mayor, unless something spectacular happens. (In the only parallel, the PCC elections of 2012, the Labour candidate got 51%, Cons 16% and Lib Dems 15%).

This obviously risks alienating non-Labour voters and politicians in the long-run. Given how successful current arrangements are claimed to have been, it is very unclear why risking upsetting them through the imposition of Mayor will be of any benefit whatsoever.

Who Decides How We Are Governed?

The final, and in some ways most damning, objection to the proposed new Government arrangement for Greater Manchester is that it is being imposed by central government dictat, accepted by a local political elite who have chosen to compromise on this in order to get the devolution of powers and resources they crave.

As is well known, but frequently misunderstood, Manchester City Council (not Greater Manchester) held a referendum on an elected Mayor in 2012 and rejected it. This is part of an, admittedly recent, practice in the UK that major governance changes should be subject to referenda. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, abetted by the Manchester local authorities, has chosen to up-end this new tradition and impose an elected Mayor.

Given the problems Britain is experiencing with alienation from political elites, the rise of ‘anti-politics’ parties like UKIP, and the widespread perception amongst the public that the governing classes are ‘out of touch’ – is imposing a new form of government on Greater Manchester without popular consent really a good idea? We have three examples of what the likely consequences are:

- The rejection of the Mayor for Manchester City Council in a referendum in 2012;

- The rejection of the proposed road charging scheme for Greater Manchester in a referendum in 2008;

- The appallingly low turnout for the Police and Crime Commissioner election in 2012 (14%)

At the very least the proposed changes in Greater Manchester – which obviously go a lot wider than the system of government – have all the hall marks of a policy being made on-the-hoof, behind closed doors, by small groups of like-minded people – just the sort of ingredients identified by King and Crewe which lead to monumental blunders.