George Osborne’s fifth Budget as Chancellor delivered few real surprises or big changes. Many of the detailed adjustments were trailed in advance, and only in the pensions arena did he deliver any radical measures, writes Professor Colin Talbot.

It is the pensions issue that will grab the headlines – as he intended. This was a highly political Budget (what’s new?) aimed squarely at one target – UKIP. Osborne was clearly targeting UKIPs pensioner and older worker supporters with what appear to be substantial ‘sweeteners’.

The liberalisation of pension ‘lump sum’ rules is a triple whammy – it makes pensioners with substantial pension pots feel better; it will bring forward more consumer spending in the short-term as pensioners cash-in their lump-sums; and it will net the Exchequer a nice fat chunk of extra income tax.

The fact it may leave a very nasty long-term hang-over of very old, very poor and very expensive for the taxpayers end-of-life pensioners is clearly not his problem today and can be safely left for someone else to clear up later. And of course income tax brought forward now will be income tax not available later. But in the short-term, it might just snatch some votes back from UKIP.

The Bigger (Smaller) Picture

What is becoming increasingly clear from this Budget is that hidden behind the rhetoric of ‘deficit reduction’ is a much bigger political agenda – to permanently reduce the size of the state.

The simple truth is that despite all the hype about ‘cuts to reduce the deficit and debt the debt starts to fall in 2015 long before the deficit is eliminated. This is because it is renewed growth in the economy that starts to reduce the debt problem – not deficit reduction as such. Table 1 shows this graphically.

Chart 1 GDP growth and Debt to GDP ratio

So despite the fact the national debt starts to fall – on OBR projections – from 2015 onwards Mr Osborne has chosen to carry on forcing through cuts to important benefits and public services through to 2018 and probably beyond.

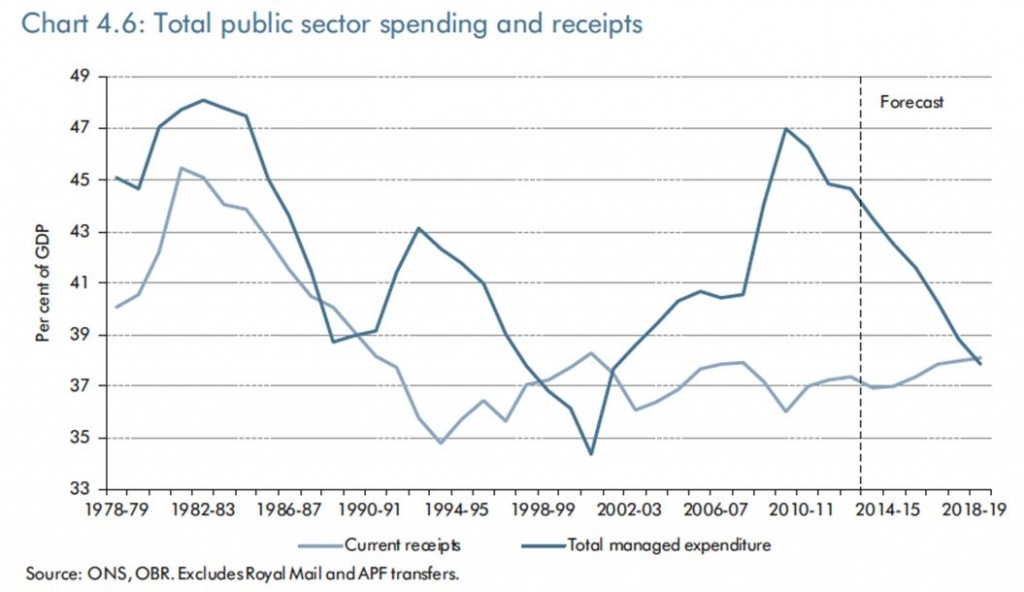

This can be seen most clearly in the OBR’s Chart 4.6, reproduced below.

The top line – which shows spending as a percentage of GDP – is in a head-long plunge towards US levels of public spending. At the rate shown, it would only take another couple of years before were down the proportion of national wealth the USA spends on collective provisions of services and benefits.

This is now being argued using the “balanced budget” fallacy – that is that only if there is no deficit, or indeed a surplus, can the national debt be reduced. This is on one – largely irrelevant – level true. The nominal (amount in actual £’s) level will not start to fall until there is a surplus – but then we have rarely had a surplus (look at Chart 4.6 again).

The truth is that in normal periods of growth a small deficit is not a problem, because growth and inflation gradually erode the real worth of the debt – in much the same way as if you have a big mortgage then inflation and increasing wages gradually erode its value relative to your income.

It is indeed curious how our political class have suddenly been converted (apparently) to a new “balanced budget” orthodoxy – something that has hardly been heard of in the British political establishment since WWII (although it is popular on the other side of the Atlantic). No-one has satisfactorily explained this sudden conversion of Labour, the Lib Dems and Tories to the new orthodoxy or why it is so essential.

The effects however are all too obvious. By 2018 Britain will have a much smaller state – in fiscal terms – than we have had for most of the post-war period. We will be moving closer to America rather than Europe in terms of the relative size of our government.

It is pretty obvious why the Tories – and maybe even the ‘Orange Book’ Lib Dems – might sign up for such a project. It is unclear why Labour has. Nor will you find any of them openly talking about the long-term consequences of a smaller state, why it should happen or how it will help national well-being.

Instead we get side-shows over a lot of minor changes to tax and spend, as we are apparently sleep-walking towards a much smaller welfare state.

One final interesting point – look at the bottom line in Chart 4.6 which shows tax income. Between now and 2018 it is projected to rise by a full percentage point of GDP. I am guessing that won’t be a focus for post-Budget discussion and analysis either. It’s certainly not something Mr Osborne will want to emphasise. Tory Tax Bombshell anyone?