UK academia is arguably at the forefront of the kind of inter-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary research needed to tackle global grand societal challenges. This distinctive mode of research aims to be policy-relevant and impactful, but by its nature is often messy, complex and difficult to communicate. Here, a group of academics from The University of Manchester and colleagues look at how to make this sort of research more helpful to policymakers.

- Nexus research has become a popular framing for research that aims to explore the interactions and interdependencies between multiple sectors.

- For nexus research to benefit policy, a trans-disciplinary approach is needed.

- Nexus-focused academics need to engage differently with policymakers to ensure research that spans sectors has influence.

- There is a need to identify a more permanent process for policymakers to engage with trans-disciplinary research to, at the very least, reduce the unintended consequences of decision making.

Why is interdisciplinary research valued by funders?

In part this is due to a growing recognition that societal challenges are complex, requiring approaches and solutions from beyond the boundaries of individual disciplines. Limiting the negative impacts of mitigating climate change as well as adapting to the consequences of climatic changes already unavoidable, is not just about engineering, but requires strategies that integrate engineering, natural and social sciences from the outset.

Many of these challenges demand integrated responses that recognise the dynamics and interdependencies of the Water-Energy-Food-Environment nexus. Transitioning to a low-carbon energy system, for example, will affect energy prices, poverty, social care, employment, and urban and rural landscapes, as well as impacting upon water and land resources, and their levels and patterns of use.

It is for these reasons that the benefits of inter– and trans-disciplinary approaches are increasingly valued by research councils, businesses and industrial funders. Programmes such as Living with Environmental Change, LWEC, (EPSRC) and the Nexus-network (ESRC) are evidence of this, as are concepts such as ‘nexus-thinking’ – which actively encourages researchers to direct attention to intersections between traditionally separate policy challenges.

Despite all this support, there is little to suggest that this approach is finding its way into mainstream UK or EU governance. Policies tackling grand societal challenges continue to focus on either water, energy, food or the environment, which leads to unintended consequences. For example, the UK 2012 Bioenergy Strategy doesn’t properly account for impacts of the targets for food, water and land-use, despite clear direct implications of increasing bioenergy production. In another example, the UK renewable heat incentives skew research and development for anaerobic digestion towards energy generation. Whilst this may be good for low-carbon energy production, this disincentivses the production of good quality digestate – an organic fertiliser that reduces the environmental impacts of UK agriculture.

What is needed to get ‘nexus’ research into the policy process?

At a recent EPSRC Nexus workshop we discussed the unhelpful chasm that exists between researchers and those who can use our research insights to effect change in policy and planning around complex issues. Recognising that policies designed by one particular government department have impacts that spill over and affect the objectives of others, we concluded that research on system interdependencies (‘nexus research’) is essential to seeking systemic solutions to problems, but new mechanisms within policy making to ensure it can have influence across departments, are critical. We queried whether there were sufficient individuals or groups who were able to ensure that an energy policy from BEIS– such as anaerobic digestion for example – does not overlook other environmental (Defra-related) and social (Housing, Community and Local Government-related) consequences.

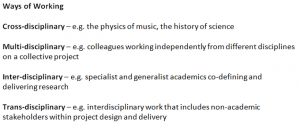

If the organisation within government means conclusions from ‘nexus’ research is more difficult to target at policymakers than traditional research, then a different mechanism is needed or a whole suite of evidence for or against policy interventions may end up being ignored. A start would be to ask whether this type of work has any audience within policy making already. If it does, is it feasible to engage that audience with the research at a very early stage – so called ‘trans-disciplinary’ research – where the ‘research team’ includes stakeholders from outside of academia? If not, what else is needed for the complex empirical insights generated by nexus research to influence policy?

Stakeholders have much to contribute, for example providing data as well as a nuanced understanding of the technological and social dimensions of specific case studies. Embedding stakeholders within research can lead to more rigorous results, but perhaps more importantly, builds relationships to develop a mutual appreciation. Together, research teams that include non-academic stakeholders can deepen their grip on of how innovation is developed and implemented, and likewise how successful policy interventions emerge.

Recommendations

Expecting analysis that cuts across the water-energy-food-environment nexus to combine knowledge and information into neat, all-encompassing models and datasets that can be interpreted into a ‘right’ answer to a problem is unrealistic –policymakers are usually more aware of this than anyone! For nexus research to benefit policy, a trans-disciplinary approach, and an evolution of cross-cutting networks and structures within the policy environment, are critical factors.

For now, identifying those already engaging with nexus-type research, and building on those relationships through trans-disciplinary projects, is an important step towards improving the value and impact of nexus research.

Nexus-focused academics need to engage more with policymakers to explore better ways to engage a wider pool of stakeholders in this type of challenge-led research.

There is also a need for researchers to work with policymakers to trial new mechanisms or structures that can influence across departments. This could begin with a series of interdisciplinary two-way policy placements, with secondees working across departments (government or academic), moving monthly to provide some level of ‘interdisciplinary facilitation’, tackling communication barriers and providing new networks.

Increasing the use of a trans-disciplinary approach leads to more ‘messiness’, is more time consuming than traditional approaches and brings new challenges. But it will be worth it if it means we can help policymakers tackle the complex environmental problems we’re facing, and make us genuinely more resilient to the ‘unknown unknowns’.

Perhaps then, a place for a more permanent structure for engaging with trans-disciplinary water-energy-food nexus research can be identified and built into the UK’s and EU’s policy making infrastructure to, at the very least, reduce the unintended consequences of decision making.

Blog authors: Alice Larkin, Claire Hoolohan, Iain Soutar, Carly McLachlan, Maria Pregnolato, Kit MacLeod, James Suckling