The global transition to net zero hinges on securing minerals such as lithium and cobalt, which are critical for use in renewable energy technologies. Despite its rich mining heritage and expertise, the UK faces challenges in rebuilding a resilient and ethical critical minerals sector. The UK government has emphasised the importance of securing supplies of critical minerals to the UK’s economic growth and security, industrial strategy, and clean energy transition. In this article, Xintong Cao, Professor Maria Sharmina, and Dr Rosa Cuellar Franca explore how the UK can position itself as a global leader in creating a resilient, ethical and an employment-rich net zero future.

- The UK government expects cobalt and lithium demand to rise by up to 45 times by 2030, to be met mainly through imports, which could undermine the resilience of our domestic supply chain.

- Cobalt extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) accounts for more than half of the global cobalt market.

- To enhance the resilience and ethical underpinning of the UK’s critical minerals supply chain, policymakers should revitalise domestic metal mining with targeted financial support and develop indigenous partnerships with mineral-rich countries.

The UK’s mining legacy and modern potential

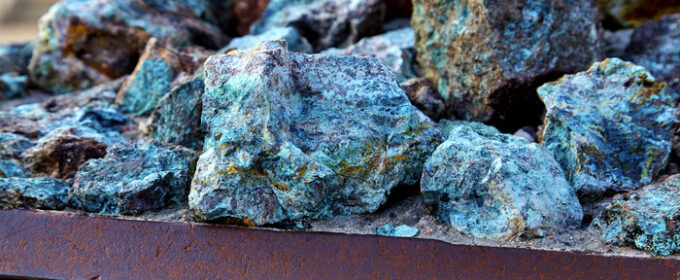

Critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and copper underpin renewable energy technologies. For instance, the electrification of our transport system will rely heavily on cobalt containing equipment. Lithium-ion batteries that store energy and propel our electric vehicles also rely on cobalt to provide heat resistance and extend battery lifespan.

The UK has a strong mining heritage and can access a skilled labour force with geological expertise. Tin and lithium mines in Cornwall offer the prospect of securing some domestic supplies of critical minerals whilst also strengthening its negotiating position on the international stage. However, the UK has a relatively small critical minerals mining industry and lacks midstream processing facilities and capacity to convert raw minerals into battery-grade materials or aerospace alloys. With UK demand for lithium and cobalt projected to increase by up to 45 times by 2030 compared to today, the country will continue importing critical minerals, particularly from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) which accounts for more than half of the global cobalt market. However, such reliance exposes vulnerabilities in the UK’s ethical sourcing and supply chain resilience, with cobalt mining in the DRC facing environmental, social, and economic risks in its mining operations.

In 2023, the then UK government published its refreshed Critical Minerals Strategy. The strategy prioritised support for domestic exploration and extraction, diversification of supply chains, international collaboration, and the strengthening of environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards to ensure transparent supply chains. However, the Strategy appeared to lack policy coherence and the necessary policy support levers to propel it forward – for example critical minerals did not feature in the 2023 Green Finance Strategy, indicating insufficient cross departmental coordination.

Recognising the importance of critical minerals in delivering economic growth and net zero, the current UK government is expected to introduce a new Critical Minerals Strategy later this year, which will optimise domestic resources, enhance international collaboration, and secure UK supply chains in the long term. To meet these ambitions the government must demonstrate cross departmental coordination, recognise operational gaps and the dearth of domestic processing facilities, and move to encourage sustainable mining in the DRC.

Building an ethical and resilient supply chain

Our research at The University of Manchester found that the downstream users of critical minerals, such as EV manufacturers, were seeking practical incentives to aid them in the responsible sourcing of critical minerals in the DRC. Our analysis also found that integration of artisanal small scale mining groups, the dominant processors of lower grade ores in the DRC, into the supply chain alongside a wider formalising of the sector would most effectively address supply chain sustainability risks. Further, we identified five measures that would incentivise stakeholders to source their critical minerals responsibly and must be considered by the government in the preparation for their new strategy to ensure the strategy is both ethical and resilient: regulatory reforms, multi-stakeholder collaboration, financial support, indigenous leadership, and innovation driven transparency of supply chains.

Improve regulation to safeguard and promote ESG standards

With investments and innovation in supply chain traceability, the UK should establish legally binding ESG standards integrating critical minerals into decarbonisation frameworks across sectors to address policy fragmentation. It should safeguard indigenous interests by granting consent through partnerships like Free, Prior and Informed Consent agreements that promote indigenous leadership and environmental co-management.

A system of anti-corruption and anti-bribery legislation could enhance supply chain transparency by mandating ESG due diligence aligned with international standards and implementing real-time market tracking. This measure could be modelled on Australia’s strategy which requires ‘participation in technical standard-setting committees’ and ‘streamlined traceability and certification’.

We suggest establishing information exchange centres and an advisory service, leveraging the UK’s global leadership in engineering management, finance and consulting. The UK can thereby position itself as a global leader in ethical mining investment and advising, with relevant governance experience, ESG standards and legislative frameworks that can be exported globally.

Revitalise domestic heritage sectors with local partnerships

Reviving dormant mines like the South Crofty Tin Project in Cornwall, could accelerate deployment of facilities and create jobs while training local groups in sustainable techniques. For example, Cornwall’s critical minerals hub has catalysed £186m in facility deployment and supported up to 320 permanent jobs and an estimated 1000 indirect employment opportunities locally. Partnering with educational institutes to launch pilots such as skills transfer and apprenticeship programmes would address skills shortages in metallurgy and mining engineering. Scaling such pilots might grow the UK’s mining and processing labour force by 30% by 2030. While not eliminating import dependence entirely, domestic metal production from revived dormant mines like South Crofty would partially reduce UK’s reliance on externally dominated supply chains.

Provide targeted financial support

We recommend that the remit of specialised financial mechanisms such as the UK Infrastructure Bank or, the Circular Economy Fund in Wales should be expanded to invest in facilities to recover critical minerals such as lithium and cobalt from end-of-life EVs and batteries (mirroring Canada’s Critical Minerals Infrastructure Fund). Research and Development tax credits could also incentivise companies to adopt circular design principles and reprocess mine waste (as seen in Australia’s Future Battery Industries Cooperative Research Centre).

Strengthen global collaboration with mineral-rich countries in the Global South

The UK government has recently secured agreements and partnerships with some mineral-rich countries, but with less emphasis on countries in the Global South. Signing partnerships with countries such as the DRC dominant in cobalt and copper to co-invest in ethical mines, can help enforce the UK government’s own guidance on investing and developing in critical minerals processing in Africa. Such partnerships could follow the example of the Sustainable Critical Minerals Alliance aiming to collaboratively develop sustainable and inclusive mining practices and sourcing critical minerals among other global peer members. These collaborations would reinforce the resilience and ethics of the UK’s critical minerals, while exporting domestic expertise and talent in mining and ethical governance.