Changing social norms and the COVID-19 lockdowns have drastically shifted how we utilise the internet to conduct our daily lives, creating a rapid increase in home/hybrid working and online shopping. In this article, Professor Cecilia Wong and Dr Helen Zheng demonstrate how high quality, reliable and good coverage of telecommunication infrastructure has resulted in differential locational advantages and socio-economic outcomes.

- Research and data from The University of Manchester has uncovered a spatial divide in broadband coverage, accessibility and speed across the UK and between rural and urban areas.

- Our research has identified links between ultra-fast broadband provision and the size of areas local economy and labour productivity.

- Place based approaches are key to addressing gaps and unlocking access – especially for rural and coastal areas.

Post-COVID digital landscape

There has been major improvement in the provision of ultrafast broadband (>300 Mbps) in the UK in recent years. According to Ofcom’s 2023 Connected Nations report, gigabit-capable broadband has already reached 78% of residential premises (77% of all premises), which means users can buy different speeds depending on the service offered by the internet service provider.

This rapidly transformed landscape is mainly achieved through the provision of full-fibre broadband. Full fibre is one of the broadband technologies – in a full-fibre connection, the connection between the exchange and the premises is directly provided over fibre. It can support speeds over 1 Gbps (1000 Mbps). Full fibre broadband was at 57% of residential premises (56% of all premises) in 2023, representing a rapid increase from 42% in 2022 and 4.8% in 2018.

The importance of speed

Speed matters greatly in broadband accessibility as it affects the internet search and high frequency trading, uploading and downloading speeds, as well as ensuring stable online access with simultaneous users – an important consideration when several members of a household may be studying or working at home and taking online meetings.

An Ofcom commissioned study in 2018 found that broadband investment on speed improvements had resulted in an increase in the UK GDP at 0.47% per annum (a 6.7% total GDP increase) between 2002 and 2016. Our own University of Manchester spatial analysis found that there are some weak relationships (tested to be statistically significant) between access to ultra-fast, full fibre and gigabit broadband provisions and the size of local economy and labour productivity.

A spatial divide

Across the UK, 97% of all residential premises have access to superfast broadband of at least 30 Mbit/s. However, a closer look shows that England, Scotland and Wales (55% or less) are lagging behind Northern Ireland (90% and over) in a major way in terms of gaining access to full fibre broadband, and the spatial divide is also witnessed in gigabit capable broadband.

Our data also highlights major urban/rural differentials in England, Scotland and Wales: while 82% of residential premises in Northern Ireland’s rural areas have access to full fibre/gigabit capable provision, the comparable figures for England, Wales and Scotland are at least halved.

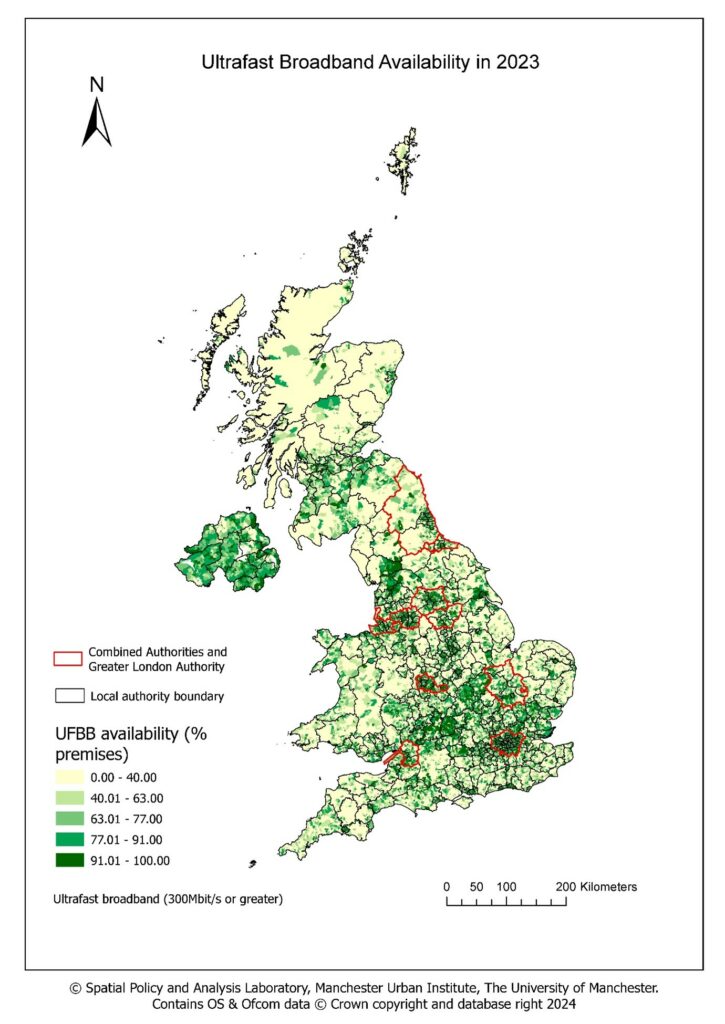

The uneven spatial distribution of ultra-fast broadband access is mapped in Figure 1. In addition to highlighting the differentials across the four nations and the urban-bias of provision, it also shows that combined authorities which have larger peri-urban catchment areas (such as the North East, South Yorkshire and Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Combined Authority areas) display more varied density and coverage of ultra-fast broadband.

Funding and spatial bias

As pointed out in the Ofcom Connected Nations 2023 report, there is a vicious cycle of development as operators are mainly focusing full-fibre deployment in areas that already have superfast broadband. There is a reliance on government schemes to provide funding to improve broadband coverage for hard-to reach areas. The ‘transformational’ broadband connectivity in Northern Ireland has been the outcome of Project Stratum (a move to improve broadband connectivity by extending Next Generation Access (NGA) broadband infrastructure to approximately 81,000 premises across Northern Ireland), with a £150m (out of £165m) funding boost from the UK Government. This was, however, achieved under the special deal of the confidence and supply agreement between the Democratic Unionist Party and the Conservatives after the 2017 general election.

It is important to note that telecommunications is a reserved power of the UK government which has primary responsibility for broadband policy and coverage targets, though the delivery of broadband infrastructure projects often involves local authorities and the devolved administrations. When examining the funding distribution of Building Digital UK (a UK government executive agency, responsible for bringing fast and reliable broadband and mobile coverage to hard-to-reach places across the UK) for superfast broadband development in 2020, it is clear that has been a strong spatial bias of government spending as 73% was for England but less than 10% for Wales.

The latest development highlighted in the Connected Nations report is that the government has started Project Gigabit (over £5bn) in September 2023, aiming to cover 1.1 million premises across the UK. There are also plans for the three devolved nations, with Scotland’s Reaching 100% (£600m) the most ambitious and Wales’s £57m Superfast Cymru the most modest. This means that there are likely to be shifts in the spatial pattern, although the pattern would be one continued with spatial variations given the path dependent nature of broadband investment with a continued focus of full-fibre deployment in those areas that already have superfast broadband.

Policy commitments and pathways

As our own findings show links between access to ultra-fast broadband provisions and the size of local economy and labour productivity, it is clear that broadband access should be firmly embedded into national and local agendas (or government strategies with ambitions for greater social equality). A placed-based approach will be crucial to reducing the unequal distribution of ultrafast broadband. The National Infrastructure Commission has also recognised the importance of a place-based approach for infrastructure development, stating “The role that infrastructure can play in levelling up economic opportunities across towns and cities in English regions is one of three strategic themes shaping the Commission’s work programme leading up to the second National Infrastructure Assessment.”

Despite the former government’s policy commitment to improve broadband connections to the very hard- to-reach premises in rural and coastal areas, the target was seen as overambitious due to the lack of commitment of sufficient funding.

With a new government, a placed-based approach could award more powers to combined authority mayors, such as North Yorkshire and East Midlands, to make long-term strategies and prioritise investment. Empowering local planners, working in tandem with communities to remove red tape and designate where improved broadband infrastructure projects are prioritised, may be a key to unlocking crucial access for some rural and coastal areas.

The lack of clarity on ‘how and where taxpayers’ money will be spent’ has also provided less impetus for investors in the industry. A place-based approach, which tangibly shows the outcomes of investment in communities, could address this gap and encourage more local investment.

The dramatic turnaround of broadband provisions across urban and rural areas in Northern Ireland, however, serves as an exemplar (which government, civil service working with industry and Ofcom could use as a blueprint), demonstrating that things can be done if there is a political will and the backing of funding resources.