It is estimated that only 17% of victims of sexual violence report the crime. This underreporting of sexual harassment and violence against women and girls (VAWG) on public transport hampers efforts to design evidence-based safety measures, leaving women to navigate unsafe conditions that undermine their mobility and freedom. Reducing gendered violence on public transport is a key factor that can support the government to achieve its commitment to halve VAWG in a decade. In this article, Dr Reka Solymosi highlights the importance of robust data collection about women’s experiences, including considering “near misses”, to inform interventions, alongside rigorous evaluation frameworks.

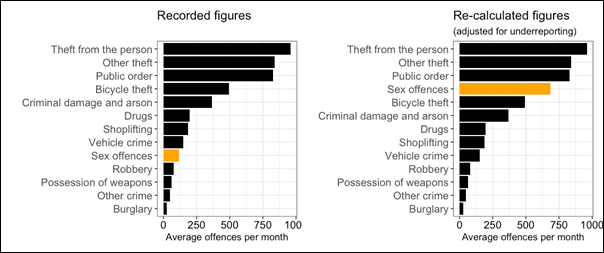

- Sexual harassment on public transport is massively underreported. While theft sees 960 reports per month, sexual offences average just 116—but true figures may be closer to 683 based on underreporting estimates (only 17% of victims report).

- Better data is key to safer transport. Collecting reports on “near misses”—incidents where women feel unsafe, but no crime occurs—can identify hotspots and prevent escalation.

- Policy must be evidence-based. Authorities should expand real-time reporting tools, integrate them into transport apps, and evaluate all safety initiatives to ensure real impact.

Data gaps limit efforts to address harassment

Campaigns like the “Report It to Stop It” (RITSI) initiative show how targeted approaches can increase reporting rates without raising fear of crime. However, these successes are often uneven. Research from The University of Manchester found RITSI was effective on the London Underground but had limited impact on bus networks for example.

Both fear and reality of victimisation shape how women use public transport, leading many to avoid it entirely or adopt self-protective behaviours. My research, using an experience sampling method via a mobile phone application, demonstrates that fear of crime is shaped by situational and environmental context, as well as everyday experiences. The results reveal that understanding the context around women’s experiences of victimisation and fear is important to shape evidence-based initiatives that tackle this. Yet many incidents go unreported due to inaccessible reporting systems or a lack of trust in authorities. This absence of reliable data creates a vicious cycle: without a clear picture of the problem, authorities struggle to develop targeted interventions.

For context, theft is one of the most reported crimes on London’s public transport system. Between March 2019 and March 2020, the British Transport Police recorded an average of 960 theft incidents per month compared to an average of only 116 reports of sexual offences per month. Theft is well-reported because victims often need to address practical consequences, which leads to higher visibility in crime statistics. In contrast, sexual offences are vastly underreported. The Office for National Statistics estimates that only 17% of victims of sexual violence report their experiences. If we apply this estimate to the recorded monthly average of 116 sexual offences, the adjusted figure could rise to 683 incidents per month, jumping ahead in the official crime statistics (see Figure 1). This contrast illustrates how reporting shapes our understanding of crime: the more something is reported, the more visible it becomes in the data.

Furthermore, the lack of evaluation frameworks means that even when initiatives are implemented, their success remains uncertain. For example, many transit authorities have recently launched campaigns promoting indirect bystander intervention to address harassment, yet little to no research exists on evaluating their impact. Without proper evaluation, it remains unclear whether these campaigns achieve their goals or inadvertently cause harm by increasing the risk to those who intervene or creating a false sense of security. This absence of rigorous assessment risks wasting resources on ineffective solutions or, worse, deploying interventions that unintentionally worsen the problem. Evaluation is essential to ensure these efforts work as intended and do not lead to unintended negative outcomes.

Research insights: a path forward

Research from The University of Manchester underscores the importance of collecting comprehensive data to inform policy and practice. Campaigns like RITSI provide a promising model for initiatives aimed at driving better reporting. Findings from our time series analysis of reported unwanted sexual behaviour incidents suggest the RITSI media campaign waves are followed by an increase in crime reporting which is not explained by an increase in the prevalence of sexual assaults.

Dynamic and context-sensitive approaches to data collection further enhance understanding of safety perceptions. My research mapping people’s fear of crime across their daily travel routes illustrated the importance of situational and spatial data for understanding when and where people feel safe and unsafe, using this to address their transport safety concerns.

Another way to gain insight is to capture data on “near misses.” In high-risk fields like aviation and nuclear power, studying near-misses helps identify the causal and situational factors that lead to serious accidents. Similarly, my research used reports of non-criminal but worrying incidents to identify hotspots for potential hate crimes. Applying this approach to VAWG, listening to women’s shared experiences of “near-misses” can help us understand the problem’s scope and pinpoint conditions enabling such incidents. These incidents—where women feel unsafe or threatened but no crime occurs—are often overlooked yet profoundly impact perceptions of safety and willingness to use public transport. Including near-miss data in reporting systems provides a richer understanding of safety challenges and helps pinpoint conditions that enable harassment.

Lastly, evaluations of safety initiatives reveal the importance of monitoring both intended outcomes and potential unintended consequences. Our realist evaluation of RITSI revealed that it increased reporting rates on the London Underground, though its success varied across different modes of transport. Understanding these discrepancies is key to refining such campaigns and tailoring them to specific contexts.

Policy recommendations for safer public transport

Supporting the government’s vision for tackling violence against women and girls, we urge transport authorities (regional and national) as well as police forces (British Transport Police and territorial police forces) to prioritise evidence-based initiatives. For police, this means ensuring that reports of sexual harassment are taken seriously, supporting women in reporting incidents, and acting on their concerns. For transport authorities, it means making reporting easier and ensuring campaigns and interventions are based on data and evidence. Partnership working is a great way to combine strengths and capabilities in this area. Sustained funding for research that involves external organisations and universities would ensure transparent and thorough assessment of these initiatives over time.

Both local and national transport authorities need to expand public awareness campaigns that encourage reporting, using inclusive language and imagery that reflect the diversity of transport uses and users. Authorities must also close the feedback loop by showing how these reports drive real change, reinforcing trust and participation.

User-friendly tools for discreet, real-time reporting are essential. Local and national transport authorities could integrate these features into transport apps to make reporting quick and accessible, providing valuable data to guide safety measures and target resources effectively. Government legislation could be used to require private transport companies to implement such solutions.

Finally, all initiatives must be rigorously evaluated, either by government authorities or through partnerships with universities or research organisations. Too often, campaigns and intervention programmes are implemented without understanding their true impact, including unintended risks. Embedding evaluation from the start ensures that interventions work as intended or can be adapted to maximise their impact and avoid unintended harm.