The use of space-based infrastructure to support life on Earth has become one of the successes of the industry. Whether it be the delivery of global communications, navigation using GPS, or remote sensing information to support the UN Sustainable Development Goals, satellites have become an indispensable part of our modern world. However, space is becoming increasingly crowded. In this blog, Dr Peter Roberts outlines how new approaches are required to mitigate the significant dangers of debris and collisions.

- Unfortunately, space technology development in the UK for university-developed technologies is poorly supported by UK Research and Innovation, with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council shying away from supporting space technology development and the UK Space Agency focusing on industrial development.

- Mega-constellations of satellites need to be managed in a sustainable fashion to ensure the long-term accessibility of low Earth orbit and limit space debris.

- There is a need for policy to encourage the development of enabling technologies for VLEO satellites.

- VLEO is a sustainable and resilient alternative to higher orbits and has the potential to allow both business innovation to take place while limiting long-term impact. However, space policy needs to recognise the benefits of the use of VLEO and mandate its use.

Crowded orbits

A new trend has emerged in the space sector: the large-scale deployment of massive constellations of satellites in low Earth orbit to provide global communications, delivering data services even in remote locations. These services have traditionally been delivered by geostationary communications satellites from a distance of 36,000km above the Earth, which have the drawback of delays caused by the time taken for radio waves to propagate over these vast distances. In contrast, these new satellites operate at just 1,200km, providing communications comparable in speed and response times to terrestrial broadband. However, to provide these services at these lower altitudes requires ‘mega-constellations’ of thousands of satellites for continuous global coverage.

Such mega-constellations must consider the impact on the orbital environment. The growing problem of space debris has been much publicised in recent years by efforts to find ways of removing failed satellites, by the problems caused by anti-satellite weapons tests, and even by Hollywood through the visually impactful but technically questionable film Gravity. Failed satellites in most low Earth orbits continue to orbit the Earth for tens to hundreds of years, occasionally being hit by other orbiting objects and producing even more debris. Of the 23,000 objects regularly being tracked in orbit by radar, only around 15% are active satellites, the rest being space debris. New approaches are necessary to balance the need for space infrastructure against the threat of space debris.

A solution – very low Earth orbits

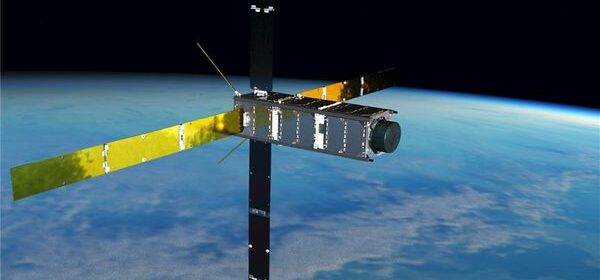

Satellites have traditionally been launched to orbits above the Earth’s residual atmosphere to avoid atmospheric drag limiting their orbital lifetime. Yet that same drag is potentially the long-term solution to the debris problem. In recent years there has been increasing interest in operating satellites in what is known as very low Earth orbit (VLEO). VLEO is defined as altitudes below which atmospheric drag has a significant impact on the design of satellites which operate there and is generally considered to be orbital altitudes below 450km. One such satellite which operates in VLEO is the International Space Station, which must be periodically boosted to stop its orbit from decaying.

Operating at these lower altitudes has numerous benefits both for the services provided and for the design of the satellites themselves. For communications, the response time is quicker even compared to the new communications constellations, and for remote sensing, the resolution of the imagery taken is improved or smaller cameras can be used, reducing satellite size and cost. Operating within the residual atmosphere provides for a more benign radiation environment, while rockets can launch more payload to lower altitude orbits, reducing launch costs. But perhaps the most important benefit of all is that VLEO is a sustainable orbital regime. Satellites and debris objects alike are pulled from orbit within a short period unless drag is actively compensated. Dealing with drag is also the biggest hurdle to overcome while satellites are operational in VLEO.

Making VLEO commercially viable

The UK is at the forefront of developments to enable the commercially viable use of VLEO. The University of Manchester leads the DISCOVERER project, a European Commission-funded study to carry out foundational developments of several emerging technologies. These technologies include materials designed to reduce the atmospheric drag, active aerodynamic control to help control a satellite’s pointing, and a new form of propulsion which collects gas from the residual atmosphere to use as a propellant.

Yet the potential for these developments still needs to be nurtured if the UK is to realise the benefits of this head start. Policymakers can support the use of VLEO as a sustainable and resilient orbital environment in a number of ways.

Policy to support tech for VLEO

There is a need for policy to encourage the development of enabling technologies for VLEO satellites. Satellites are, and will continue to be, operated in VLEO; however, the commercial viability is currently questionable. New technology and research are required to enable sustained commercial operations. Funding is required to build on the foundations and to ensure the UK maintains its global lead in the area. Unfortunately, space technology development in the UK for university-developed technologies is poorly supported by UK Research and Innovation, with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council shying away from supporting space technology development and the UK Space Agency focusing on industrial development. This must change if the technological progress made within universities is to be developed and exploited, effectively creating a level playing field for space technology development against other engineering disciplines.

International space policy changes

International space policy must come to an agreement to prioritise the use of VLEO. One could envisage a future where the vast majority of communications and remote sensing satellites are only licenced to operate in VLEO where satellite failures have little long-term consequence for the space environment. This would allow higher orbits to be reserved for science, crewed activities, and space exploration. Launches into VLEO are already considered low risk by the Civil Aviation Authority, because of the limited potential damage to other space assets and therefore limited liability to both the space operator and government. However, restricting communications and remote sensing activities to VLEO would require international agreement.

Key international policy considerations

- The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) was set up in 1993 to facilitate cooperation between states on how to tackle space debris, but the resultant non-mandatory guidelines are not sufficient and occasionally ignored. VLEO should become a specific discussion item in the IADC’s working group on space debris mitigation.

- Mega-constellations of satellites need to be managed in a sustainable fashion to ensure the long-term accessibility of low Earth orbit and limit space debris. VLEO is a sustainable and resilient alternative to higher orbits and has the potential to allow both business innovation to take place while limiting long-term impact. However, space policy needs to recognise the benefits of the use of VLEO and mandate its use.

This article originally appeared in On Space, a collection exploring how pioneering research into the space sector will continue to help impact UK and international space policy through the development of home grown space capabilities, supporting international collaborations and the levelling up of our space economy. Published by Policy@Manchester.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.