Europe is struggling through a period of exorbitant energy prices. In addition to directly hitting consumers with a higher cost of living, high energy prices will also have detrimental effects on business and industry. In this blog, Will Bodel from the Dalton Nuclear Institute examines the role of nuclear energy in reducing the cost of energy, and discusses their funding and financing.

- New nuclear energy could provide a significant amount of Britain’s energy needs, which will help insulate against future energy shocks.

- Nuclear energy can be cost-effective, but requires a sensible approach to financing, which Government must facilitate.

- Progress has been made in developing a RAB financing model. The full details of the RAB are yet to be defined, but it is important to ensure that the operational costs are reasonable.

The current energy crisis

In August, Ofgem announced that the price cap (the backstop protection limiting the unit price suppliers could charge for energy), would rise to £3,549 for October-December 2022, a sharp increase from £1,250 last winter. With forecasters predicting prices would hit £4,500 in 2023, Government announced an Energy Price Guarantee, limiting the cap to a lower level to help protect consumers, with the taxpayer compensating energy suppliers the difference.

Government’s medium-term strategy remains to be seen, but it must involve starting to put in place a more resilient energy system to prevent recurrence. While new nuclear power can do little about the immediate problem, it has an important role in the long-term reshaping of the system and preventing such vulnerability in the future.

How could such a situation have been avoided?

One answer would have been a diversification of generation capacity; a broad portfolio of generation technology reduces vulnerability when one source becomes scarce. This is hardly a shocking revelation, and the use of energy supply as leverage is also nothing new – such a sentiment was expressed throughout the 2008 Energy White Paper:

“The majority of the UK’s nuclear power stations are due to close over the next two decades. Over the same period, the UK will become increasingly reliant on imports of oil and gas, and at a time of rising global demand and prices, and when energy supplies are becoming more politicised.”

Coal use had all but vanished in the UK as carbon reductions for net zero were pursued, and only five nuclear power plants remain operational (down from 16 in 2000). Meanwhile, the expansion of renewables proves a double-edged sword as gas is needed to fill in the gaps in their intermittency.

A role for nuclear?

Electricity from nuclear is low-carbon, not reliant on resources located in politically volatile regions, reliable, and cheap to fuel and maintain. Given all this, and if almost 15 years ago it was identified that new nuclear should be built, why is Hinkley Point C still the only nuclear plant under construction?

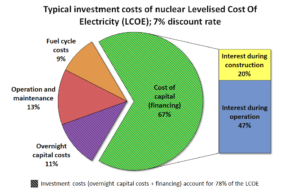

The reason is financing – a paradox exists on the economics of nuclear. Small marginal costs make nuclear power plants price competitive over their long (60+ year) lifetime, but this is only realised after the large initial capital costs are expended and the plant becomes operational. Long build times must be endured before any return on investment is seen, and it is during this long, high-risk construction period that financing costs balloon to dominate the total cost per unit of electricity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Breakdown of the nuclear levelised cost of electricity. Reproduced from NEA.

Financing options

Since Sizewell B (our most recent nuclear power plant) was built, state-financing nuclear power has been unpopular, and the huge capital costs and long repayment period has deterred private investment – alternative financing solutions have therefore been sought.

In 2012 the government committed to a Contract for Difference (CfD) for Hinkley Point C. This ensures that the operator EDF bears risk in delivering the project and funds eventual decommissioning, albeit with a government debt guarantee. Once built, the CfD guarantees EDF a minimum “strike price” of £89.50/MWh (inflation-linked, so £114 in today’s money) for 35 years after the project completion. At the time, with wholesale electricity prices just under £50/MWh, this was described by many as a bad deal for future bill payers, who are ultimately responsible for paying the strike price – but compared to today’s prices, the HPC strike price look rather better. That said, estimates from the Committee on Climate Change in 2013 predicted onshore wind costs in 2020 of £80/MWh and offshore wind £120/MWh, so the HPC strike price seemed not too bad a deal for reliable, low carbon electricity at the time.

A better deal may not have been possible using this financing method. While the strike price seems high by 2012 standards, the developer in a CfD shoulders the burden of constructing the plant – and the associated risk. Such an undertaking warrants such a strike price. The failure of other contemporary nuclear projects at Moorside and Wylfa (CfDs with lower strike prices) due to financing issues indicates how ineffective this method is for financing nuclear projects.

Alternative financing methods have been proposed, but the one identified as having the greatest potential is the Regulated Asset Base (RAB), the model used to fund Heathrow Terminal 5 and the Thames Tideway Tunnel. The RAB aims to make the whole process more affordable by empowering a regulator to levy charges on consumers while a plant is being built. While this means bill-payers will be paying for a plant which isn’t producing electricity yet, because project owners will be able to settle financing costs sooner in the life of the project (reducing the size of the green slice in Figure 1), this stops the financing costs from spiralling during the construction period. These savings can then be passed on to consumers in the form of cheaper electricity per unit, with figures of £40-£60/MWh being touted for electricity from future nuclear plants built according to this financing model.

The Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill, introducing the RAB for nuclear received Royal Assent in March, but not all the details of how it will be operated have been decided. The latest step in the process, the Government’s consultation on the RAB revenue stream, closed in August and is currently being analysed. As the details are finalised it is important that the Government, and the relevant regulator, ensure the best possible deal for the consumer.

At Manchester, our energy experts are committed to delivering an equitable and prosperous net zero energy future. By matching science and engineering, with social science, economics, politics and arts, the University’s community of 600+ experts address the entire lifecycle of each energy challenge, creating innovative and enduring solutions to make a difference to the lives of people around the globe. This enables the university’s research community to develop pathways to ensure a low carbon energy transition that will also drive jobs, prosperity, resilience and equality.