The UK’s ambition to achieve net zero by 2050 is an enormous undertaking, and many acknowledge that achieving such a goal requires an increase in nuclear energy capacity and therefore an increase in the number of nuclear sites across the UK. In this blog, colleagues from the Dalton Nuclear Institute; William Bodel, Adrian Bull, Gregg Butler, Juan Matthews and Francis Livens assess some of the questions concerning nuclear plant siting which face us.

- The UK is set to miss its next two carbon budgets, the milestones to achieving net zero by 2050.

- This coincides with annual nuclear power output in the UK being at its lowest since for 40 years.

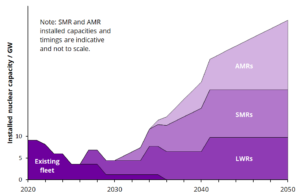

- The future vision for nuclear in the UK between now and 2050 is anticipated in three waves, with the final wave of high temperature plants offering potential beyond traditional electricity generation.

- Currently, we do not have enough sites allocated to accommodate an expansion of the nuclear sector of the necessary scale. More sites will be needed, and effort will be needed to gain the local approval needed to proceed with new nuclear build.

The challenge of net zero

In 2019, the UK government legislated to increase its previous ambitions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, committing to net zero emissions by 2050. The Climate Change Act also lays out the carbon budgets – legally binding interim targets for GHG reduction, split into periods of five years. While the first three budgets have been met, the UK is set to miss its fourth and fifth carbon budgets.

Given the challenge of net zero, coupled with the low life cycle of GHG emissions which result from nuclear power, many now acknowledge that expansion of nuclear energy is required if net zero is to be reached. Beyond the environmental motivations, the recent volatility in energy prices has also reiterated the value of a diverse energy mix in protecting energy users from sharp price rises.

Agreement that there is a future for nuclear in the UK is welcome, however time to act is now limited. The UK’s nuclear output has been shrinking since its peak in 1998, owing to the closure of ageing stations – last year’s output was less than half that of 1998, and the lowest since 1982. This lost capacity will have to be replaced before the net output from nuclear energy can increase.

The three wave strategy

To tackle this, the current “Three Wave” strategy envisages the delivery of three broad reactor types over the next thirty years:

- Light Water Reactors (LWRs), such as those currently being constructed at Hinkley Point.

- Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are small versions of LWRs, anticipated to be deployable in the early 2030s.

- Advanced Modular Reactors (AMRs), assumed to be in the form of High Temperature Gas-cooled Reactors (HTGRs), with ambitions for a demonstrator plant by the early 2030s.

The current generation of LWRs are large and complex engineering projects, with the planned nameplate capacity of Hinkley Point C to be 3.3 GW, for context – the average UK electricity demand during 2018 was 31.4 GW. Building new stations like this takes years, which adds to the overall cost of the electricity produced. By reducing the physical size of LWRs, reactor modules can be built in factories and assembled more easily on-site, reducing costs. More exotic, advanced reactor designs offer potential benefits such as greater uranium efficiency or higher operating temperatures, but are years away from deployment. High temperature reactors are useful because their heat can be used directly in industrial processes which are otherwise difficult to decarbonise, or in generating hydrogen more efficiently than is possible through room temperature electrolysis. Figure 1 shows the imminent decline of the existing reactor fleet, and the potential rebuilding with the Three Waves:

Figure 1. The decline of the existing UK nuclear fleet, and the potential future Three Waves of nuclear [adapted from NIRAB]. The LWR plot assumes successful completion of Hinkley Point C and two sister stations.

Ambitious scenarios use examples involving hundreds of reactors to provide the energy needed to replace fossil fuels, less ambitious programmes would still require many tens of reactors on tens of sites. As only eight sites have been deemed potentially suitable for the deployment of new nuclear power stations in England and Wales before the end of 2025, an unavoidable consequence of such a desired expansion of the nuclear sector is a requirement for new sites to host future nuclear plants. This is important, because new sites, i.e. those with no historic nuclear presence, will require the acceptance of new reactor build in areas with surrounding publics with no experience of, or vested interest in, a new local reactor.

Community support for nuclear

When considering new sites for nuclear stations, it is worth bearing in mind that the last UK nuclear site to be opened was Torness, where work on the site’s nuclear plant started over 40 years ago. Both the UK nuclear industry and the processes involved in granting permission to developments have changed very significantly since then – local acceptance looms considerably larger in the process than it did in the past. The necessity for new sites prompts a need for local acceptance of a sort that has not been sought for almost half a century. Assuming community support for new build, even in existing nuclear communities, could prove complacent – especially where previous plants may have been perceived to have damaged the environment or left other negative legacy behind. Important questions will be asked about many aspects of the nuclear legacy, from the traditional concerns around nuclear waste, to that of the decommissioned plants which seem to have become permanent features on the landscape.

The solution

One area where lessons for a potential solution can be found is that of efforts made to find a suitable site to host a nuclear Geological Disposal Facility (GDF). The process has been a long one, with failures resulting from opposition from county council levels in 1997 and 2013, the latter in spite of approval from the district level. The current local consent-based approach seems to be making measured progress on a GDF, with three areas currently involved in local engagement processes. This progress, while modest, might be instructive on how to progress with regional consent for new nuclear energy sites.

The Dalton Nuclear Institute has released a position paper, containing nine recommendations for government and industry. The overarching recommendation is for government to develop an integrated framework for the delivery of nuclear energy in the UK. A solid understanding of the full lifecycle of future nuclear provision will be essential to ensure that a suitable nuclear sector can be delivered by 2050.

In March 2022, the Dalton Nuclear Institute released a paper ‘Siting implications of nuclear energy: a path to net zero’ which outlines the key actions needed to deliver a responsible nuclear sector in the UK’s net zero future: https://www.dalton.manchester.ac.uk/siting-implications/

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.