Greater Manchester has seen some of the highest rates of COVID-19 and as a result has faced particularly stringent lockdown regulations. With Manchester being one of the most deprived local authorities in England, many neighbourhoods and communities were less resilient to the economic shock caused by the pandemic. In this blog, Dr Arkadiusz Wiśniowski, Senior Lecturer in Social Statistics, discusses the economic impacts of the pandemic on ethnic minorities in Manchester.

- Manchester is one of the most deprived areas in England, and has one of the highest percentages of ethnic minority population. This created a disadvantage for ethnic minority residents through the course of the pandemic.

- Policy response should consider the disadvantages faced by concentrations of ethnic minority workers in shut-down sectors, low-paid and insecure work, then aim to create better working conditions and more security for those employed in these types of work.

- There is a need to remove restrictions for, or identify ways to protect, groups with no recourse to public funds to prevent homelessness.

- Targeted upskilling of the older population from ethnic minorities, especially women and those disadvantaged due to language barriers, is needed to improve their digital skills.

The pre-pandemic picture

Manchester is the sixth most deprived local authority in England (according to the 2019 English Indices of Multiple Deprivation). Therefore, many neighbourhoods and communities in the city were always going to be less resilient to the economic shock caused by the pandemic compared with other less-deprived parts of the country. In particular, challenges for Manchester include the prevalence of poor health, low-paid work, low qualifications, poor housing conditions and overcrowding.

Ethnic minority groups also faced disparities long before the onset of the pandemic. Firstly, within the UK, ethnic minorities have been found to be most disadvantaged in terms of employment and housing – particularly in large urban areas containing traditional settlement areas for ethnic minorities. Further, all Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups in Greater Manchester were less likely to be employed pre-COVID-19 than White people. People of Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic backgrounds, especially women, have the lowest levels of employment in Greater Manchester. Finally, unprecedented cuts to public spending as a result of austerity have also disproportionately affected women from ethnic minority backgrounds, alongside White women, disabled people, the young and those with no or low-level qualifications. This environment has created and sustained a multiplicative disadvantage for Manchester’s ethnic minority residents through the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reviewing the impact

Earlier this year, I worked in collaboration with fellow researchers at the Social Statistics Department of the University, Policy@Manchester, and the Performance, Research and Intelligence team at Manchester City Council, to conduct a rapid review that aimed to summarise the economic impacts of the pandemic on ethnic minorities, with a focus on the city of Manchester. It utilised multiple articles and reports to explore various dimensions of the economic shock in the UK, linking this to studies of pre-COVID-19 economic and ethnic composition in Manchester and Greater Manchester, in order to infer the pandemic’s impact specific to the city-region. Below, I highlight some of the key findings from the review.

Insecure work

Those in insecure work are 1.5 times more likely to have been made redundant than other working age adults. People from ethnic minority backgrounds represent a disproportionate percentage of the insecure workforce, with 18% of all insecure workers being BAME, despite these groups making up 11% of the total workforce. In particular, Black people are over twice as likely to be in temporary work, and the percentage of the Black workforce on zero-hour contracts is almost double the average (1 in 20 versus an average of 1 in 36).

Policy response should, therefore, consider the disadvantages faced by concentrations of ethnic minority workers in shut-down sectors, low-paid work, and in insecure work, then aim to create better working conditions and provide more security for those employed in these types of work.

Upskilling

While the UK’s “digital divide” (the difference between those who have access to information and communication technology (ICT) and those who do not) has narrowed over 2011-2018 especially for ethnic minorities, there are still large differences between older and younger people. This is especially important for the older population from Asian ethnic minority groups, who have been shown to have lower access to the ICT than the White population.

This lower access to the ICT also highlights a need to ensure this access by, for example, investment in the ICT infrastructure in areas with poor internet coverage, and training on the use of the internet and online safety. Further, upskilling could also target those in minority populations that are expected to be most disadvantaged by, for example, language barriers when completing online forms, such as applications for Universal Credit. Thus, upskilling Manchester’s population, especially in terms of digital skills, should be a priority. This may be targeted specifically at the older working age populations from ethnic minorities.

Homelessness and Universal Credit

Although homelessness affects different types of people, no recourse to public funds (NRPF) particularly affects ethnic minority people as immigrants more often find themselves in precarious situations because of job losses and not being able to seek allowances from Job Retention or Self-employment Income Support Schemes. Further, asylum seekers and refugees heavily rely on charities to avoid homelessness.

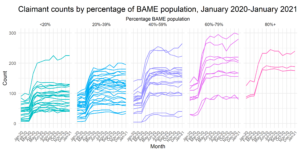

The changes in Universal Credit applications in Manchester Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs) are illustrated in Figure 1. The highest increases in the number of claimants were noted in LSOAs that have a high percentage of Black, Asian and minority ethnic population thereby illustrating a positive association between the percentage of BAME population in the LSOA and the count of benefit claimants.

Figure 1: Claimant counts by percentage of BAME population, Manchester. Source: NOMIS Claimant Count data.

There is a need to remove restrictions for, or identify ways to protect, groups with no recourse to public funds to prevent homelessness. Also necessary is specific support for ethnic minorities alongside migrant populations via an information campaign on access to benefits, social housing and other services, perhaps in their native language(s).

Targeted interventions are also required to aid economic recovery for Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups, who are represented in high numbers in self-employment and/or in shutdown sectors, together with a higher prevalence of single-earner households and a higher likelihood of having dependent children.

Take a look at our other blogs exploring issues relating to the coronavirus outbreak.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.