Today in the UK, due to early diagnosis and early, effective treatments, life has greatly improved for people living with the HIV virus. But HIV has not gone away and there are new concerns in a world of increasing sexual experimentation and online communication. In Sexual Health Week 2018, Jaime García-Iglesias explains why policies to prevent HIV infection need to consider not just sexual practices but also the role of desire and fantasy.

- This is a time of change for HIV, in particular because most people can live more or less ordinary lives with the virus. Stigma and discrimination, however, still prevail

- ‘Bug chasing’ – the eroticisation of HIV – is a growing phenomenon, being amplified by the internet age

- Sexual health and HIV prevention initiatives tend to be focused on sexual acts and practices and don’t necessarily consider the importance of desire and fantasy

- By providing safe spaces for talking about these things, where people don’t feel judged, more effective countermeasures against stigma and against HIV infection could be developed

Changing times for HIV

We live in a time of change for HIV. Far from the death sentence it once was, 2016 saw the first-ever decline in new HIV infections among men who have sex with men in four major London clinics, as well as the attainment of the UNAIDS targets in London: 90% of the people infected are diagnosed, 90% of those are on treatment and 90% of those on treatment have their virus suppressed. This has been possible thanks to a combination of factors including the reduction of waiting times between diagnosis and the start of anti-retroviral treatments, which reduces the risk of patients becoming unwell and allows the presence of the virus to become undetectable in their blood. Effectively, this means that those who are undetectable cannot pass the virus to others, regardless the type of sex or bodily contact they engage in.

Additionally, since 2015 in the UK, we’ve seen the fight of charities and other organisations for the provision of PrEP—a drug intervention that prevents people from becoming infected with HIV. Overall, this is a time of change for HIV: most of those infected can live more or less ordinary lives with minimal physiological side effects while, for the first time, people can take a medication to protect against infection even if they are exposed to the virus. The ‘diabetes metaphor’, which originated in the 1990s, is more popular than ever: having HIV is not unlike having diabetes. Nevertheless, stigma and discrimination prevail and are rampant in mainstream media and society alike.

Bugchasing: fantasy, more than reality?

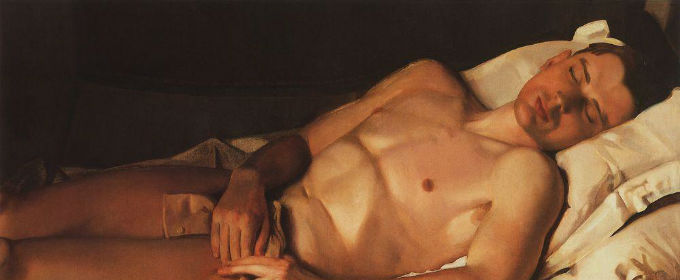

It is against this background that my research is exploring the little-known but much loathed phenomenon of ‘bugchasing’. So-called ‘bugchasers’ are gay men who eroticise HIV infection, seeing the virus as a way to attain profound, life-long intimate connections with others. Some of them see the virus as a form of gaining masculinity, while others hope to become part of a close-knit community. While my research does not aim to judge these men, I do recognise that their desires can be shocking. Few people, particularly gay men, are oblivious to the 1980s and early 1990s images of men with AIDS on their deathbeds, even if we are aware of the fact that HIV is no longer a death sentence.

While many people argue that bugchasers and their desires are as old as HIV itself, I believe that they belong to the internet age: they thrive through Twitter conversations and hashtags; create profiles in dating sites and exchange views and pornography in forums. Most of the research on bugchasing acknowledges its strong online character but fails to discuss whether bugchasers actually exist offline which is surely a key point to establish. The available evidence seems to suggest that most of the men who engage in bugchasing conversations online do not actually seek to engage offline. Understanding why and how these men fantasize about HIV, without actually seeking it offline, is key to determining the need for health promotion programmes.

Of acts and desires

Sexual health initiatives—and HIV prevention—tend to be focused on sexual acts and practices that might be modified to be made ‘safer’. However, very little attention has been paid to sexual desires. I suggest that it is timely for sexual health initiatives to focus on the desires: desires such as those that fuel some men’s fantasies of HIV infection as a route to community, intimacy, masculinity, and power. By focusing on desires, we can bridge the unsurmountable sense of shock and horror that sexual health providers and policy makers may encounter in dealing with people who appear to willingly seek HIV infection.

We all long for profound intimacy and deep connection, and public health programmes should focus on the complexity of desire as much as they do on what are deemed to be changeable sexual practices. For this to happen, we need the provision of safe-spaces on and off-line where service users can express their desires and talk with others about them. While these spaces could allow potential bugchasers to find meaningful alternatives to what they experience as ‘(un)natural’ desires, they could also provide spaces where the fantasies of HIV infection could be discussed alongside the continuing ‘realities’ of HIV infection (such as co-infection with Hepatitis C, side effects of anti-retroviral drugs, long-term uninsurability, fatigue, depression, and so on). Illicit substance and heavy alcohol users could explore how their feelings also contribute to their practices. These should not be spaces for condemnation but for facilitating understanding. Such initiatives are being piloted by several organisations, not least the Manchester based LGBT Foundation through their ‘one-to-one advice’ programme. Evaluating the outcomes of such interventions is crucial for the future of sexual health and policy making.

Lessons in desire

The association of HIV with promiscuity, homosexuality, or sin is still common, and in a culture that continues to stigmatise HIV infection, it can be difficult to disassociate bugchasing desires from uncontrollable sexualities and/or a desire for death. However, bugchasing desires (as opposed to actual bugchasing) are indicative of the ways in which the meanings we attach to stigmatised conditions are malleable and open to change. This is not to advocate that we encourage people to seek infection with HIV. Rather it is to argue that by studying the tools and processes whereby HIV is given new meaning as something desirable, we can examine how foe is turned into friend. We can then explore the possibilities for sexual health providers, in collaboration with people who ‘desire’ infection and those living with realities of HIV infection, to co-develop new meanings for the virus, meanings which allow those infected and those at risk of infection to live more connected lives.

In November, an event titled “LHIVES: Narratives of HIV” will focus on how researchers and practitioners can join forces with people living with HIV to explore the anti-stigmatising meanings of the virus by showcasing the diversity of stories of HIV, the many lives of HIV. This is just part my current effort to engage with public health practitioners who encounter the force of fantasy and desire in their daily work. In addition, I am also interested in whether the particular relationship of desire and reality in bugchasing is mirrored in other practices, and how other researchers and practitioners are engaging in these.

Bugchasing is a shocking story about HIV that is currently grabbing the attention of those concerned with sexual health. But while the bugchasing story may be ‘shocking’ it may also represent an opportunity, a platform from which to develop more effective countermeasures against stigma and against HIV infection.