All innovation in health and social care has the same final common pathway: health and social care professionals doing something new or different. There are numerous theories of behaviour and behaviour change, so people who are trying to innovate can find it confusing and difficult to meaningfully draw on behavioural science. Here, Drs Jo Hart, Lucie Byrne-Davis and Eleanor Bull, Health Psychologists, discuss the current research about health professional behaviour, introduce the work they are doing in studying the translation of research to improve practice, and outline some implications for policy.

- Developments in behavioural science are giving researchers greater insight into how professional training can create sustainable changes to practice

- ‘Health Partnerships’ are a promising, new way to promote better practice in healthcare systems around the world

- Behavioural science research is of increasing importance as the UK health system moves towards ‘new models of care’

- Moving from a ‘competence’ to a ‘behavioural’ training models should be a key goal of professional education policies

Behavioural science in 2018

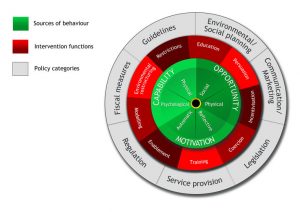

We are reaching the end of a decade in which psychology and the social sciences have made strides in synthesising the many theories of behaviour that have developed over the last 100 years. In 2011, Michie and colleagues published the Behaviour Change Wheel, including the COM-B framework. The COM-B is elegant in its simplicity, summarising that behaviour (B) is determined by three broad factors: capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M). Like all summaries, the COM-B framework’s simplicity belies the complexity beneath, but as an entry point to behavioural science, it is proving to be enormously helpful.

Another innovation from the same stable is a taxonomy of techniques to change behaviour. The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy v1 describes the 93 individual techniques which can be used to change behaviour. These active ingredients of behaviour change are useful particularly when trying to translate evidence across contexts because the type of technique can be described at its fundamental level e.g., setting an outcome goal or giving a self-reward.

The importance of these developments cannot be overstated, as they provide an elegant, shared language that crosses the academic – practice – policy boundaries. We have been using these tools to study and drive health professional practice change in two important contexts.

Health professional education and training

Competence-based education for health professionals has been the goal for some years now. The focus of this is that a health professional should have the knowledge and skills they require to practice in the right way and that they are able to demonstrate these through assessments.

This focus on competence as the means to driving practice is at odds with prevailing behavioural science, because it does not explicitly focus on the opportunity and motivation parts of the COM-B, nor evaluating actual practice change. Educators and trainers frequently report that, despite health professionals being able to prove their knowledge and skill at a point in time, they do not necessarily change their practice in real life settings following receiving new guidelines or attending training, for example, following an intervention to change their practice. The practices, or behaviours, that might not change can include not following clinical guidelines, not adopting new innovations or not engaging in infection control measures, such as handwashing. The lack of change following education and training has been a particular concern of organisations engaged in health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries through health partnerships.

Health partnerships are collaborations between high- and low- or middle-income country organisations which work together over a number of years to strengthen health systems through, for example by the higher income partner organisation offering specialist training and ongoing support. Realising that health partnerships were attempting to change and sustain change in health professionals, we established The Change Exchange, a hub for behavioural scientist volunteers to work with health partnerships.

Behavioural scientists volunteer and are placed to work with a health partnership, both in the UK and a low- or middle-income country. They observe the activities of the partnership, work with the partners to establish the drivers of practice, the behaviour change techniques that are and could be used to change practice as part of training and other activities, and manage research about practice change. Crucially, using the frameworks, the volunteers leave a legacy of understanding change, which the health partnerships can continue to use and develop. See The Change Exchange for examples of the work and Byrne-Davis et al., 2017 for an overview of behavioural approaches in health partnerships.

Organisational development

New models of care and new types of workforce necessitate different ways of working for health professionals. Organisational change often happens at a policy and procedure level but how much do health professionals know about what they have to do differently, as change is introduced and what methods best support and sustain change?

Working with Health Education England in the North, we studied NHS new models of care vanguards at the level of individual teams who were being required to make changes to the way they practised. In the Teams Together project, we worked with teams to help them make changes, whilst also studying how change was happening. This type of “participatory action research” is a great way of involving people in research and ensuring that research benefits participants even as it is ongoing.

We found that individuals within teams were not sure how their individual practice should change in response to higher level organisational policy change, even when they were aware of the reasons for changes and agreed with them. This was a really important finding because it was clear that people needed more guidance in working out what they could and should do differently to make the changes and improvements that the organisation wanted. We found that teams felt that change was often imposed and that they felt better when they were in control of change. This was not a surprise, as previous research has shown repeatedly that people are more engaged in change when they have some control and input into what and how change happens.

We introduced methods to the clinical managers and the organisational development practitioners responsible for change. They found the COM-B framework enlightening, helping them to understand why change was difficult and what they could do to help. We developed a five-stage process for managers and change practitioners to use, based on behavioural theories and using established methods. Up-skilling clinical managers, leaders and organisational development practitioners within an organisation, using the frameworks, is a way to make behavioural science accessible within organisations. As we know, health and social care organisations are always changing!

Policy implications

Education and training should be based on a ‘behavioural’ rather than a ‘competence’ model

- Curricular guidelines, written by regulators and professional bodies, such as the General Medical Council and Royal Colleges, should include reference to intended learning outcomes that address opportunity and motivation, rather than ‘capability’ (competence).

- Commissioners of education and training for healthcare professionals, e.g., Health Education England, Clinical Commissioning Groups and NHS Trusts, should require educators to evaluate the effectiveness of the courses on the basis of changes in behaviour and/or behavioural determinants i.e., capability, opportunity and motivation.

- Education institutions should require their health professional education programmes to show how they are addressing the wider determinants of practice i.e., the opportunity and motivation of their trainees.

Organisational development should include a focus on the behaviours of the healthcare professionals involved in change

- Health and social care organisations should equip their organisational development teams with behavioural theories and methods, to increase the focus on the behaviour changes required of the individuals undergoing change.