Tom Arnold, a postgraduate researcher of economic development in Northern England, examines current housing policy in Greater Manchester and the challenge to develop a housing strategy which supports its growing economy whilst simultaneously tackling homelessness and deprivation.

- Housing policy in Manchester is under scrutiny and campaign groups are concerned that the city centre is becoming dominated by apartments for affluent urban professionals whilst families and lower-income renters are pushed to margins.

- However, we are not yet witnessing the Londonification of Manchester’s housing market, and home ownership remains a realistic prospect for many residents on or above the full-time average Greater Manchester salary.

- Greater Manchester’s challenge is to develop more family homes whilst simultaneously making available more homes for social rent and tackling homelessness.

- The second draft of the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF) is likely to focus on development in outer towns and boroughs and will provide some indication of how Mayor Andy Burnham and other city leaders see development policy evolving over coming years.

The Housing Policy Debate

Housing policy in Manchester is under scrutiny as never before. The City Council’s approach to development has been highlighted in the Guardian and Manchester Evening News over recent months, and its ruling Labour Party group is reported to be increasingly at odds over how to build more affordable housing. Even Jeremy Corbyn has weighed in, with the leader of the opposition warning of Manchester “going the same way” as London.

Much of this debate centres on the type of housing built in recent years within the three square miles or so of Greater Manchester’s urban core, stretching from Piccadilly Station in the east to Salford Quays in the West. According to the online estate agent Zoopla, the average flat in Manchester City Centre now costs over £216,000, an increase of 5.8% in the last 12 months, whilst the average rent for a 1 bed flat now stands at £866 per month. Campaign groups such as Greater Manchester Housing Action and Manchester Shield are increasingly vocal in demanding an alternative approach to planning, with concerns that the city centre is becoming dominated by apartments for affluent urban professionals whilst families and lower-income renters, are pushed to margins. Whilst Manchester City Council has defended its approach, arguing high land values in the city centre mean it is more realistic to develop social housing and affordable homes in areas with less demand, it is clear the debate over housing policy is not going away.

Rapid Regeneration

The roots of this controversy lie in the approach to urban regeneration adopted by long-standing City Council leader Sir Richard Leese and the recently retired Council chief executive Sir Howard Bernstein back in the late 1990s. In the aftermath of the 1996 IRA bomb, encouraged by the work of New Labour’s Urban Task Force, the duo sought to reverse the fortunes of a city centre in decline since the 1960s by attracting professional services firms and their young, affluent employees into the area. Between 1998 and 2011, Manchester city centre saw a 44% growth in private sector jobs, and an increase in the resident population by 20,000. Manchester’s rapidly rising skyline was testament to the ambition of its leaders to re-urbanise the city by increasing population density and making it more attractive to the burgeoning ‘creative class’.

A decade later, the Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) embedded the Council’s vision of urban renaissance into local economic development strategy. The report has guided much of Greater Manchester’s approach to economic strategy over the last 10 years and suggested more should be done to encourage investment in the city centre. On housing, the MIER warned against mixed development such as the provision of homes for social rent within developments otherwise aimed at young professionals, suggesting that this “may make it more difficult to attract those firms and individuals who do not want to locate in such mixed communities”. City Council planning officers have been reluctant to demand affordable housing provision in city centre development for fear of discouraging investment, while many developers argue the cost of buying and remediating city centre brownfield sites makes the inclusion of affordable units unviable.

The Londonification of Manchester’s housing market?

It is tempting to view this debate through the lens of the housing crisis which has beset London and the South East over the last decade. Yet, whilst housing costs have risen dramatically in the city centre and other hotspots such as Chorlton and Didsbury, prices in other parts of the city-region remain relatively affordable. Some of the cheapest properties are available within walking distance of the centre. At the time of writing, there were several newly built, 3-bed terraced and semi-detached properties for sale on Rightmove in Cheetwood, just over a mile from Victoria Station, for £130,000. Similar properties are available in Monsall, to the north east of the city centre, for around £120,000. Slightly further afield in popular Levenshulme, five minutes by train from Piccadilly Station, the average property price stands at around £166,000. Looking at the prices of properties within easy commuting distance from the city centre, it is clear we are some way off the Londonification of Manchester’s housing market. Homeownership remains a realistic prospect for many residents on or above the full-time average Greater Manchester salary of £26,000.

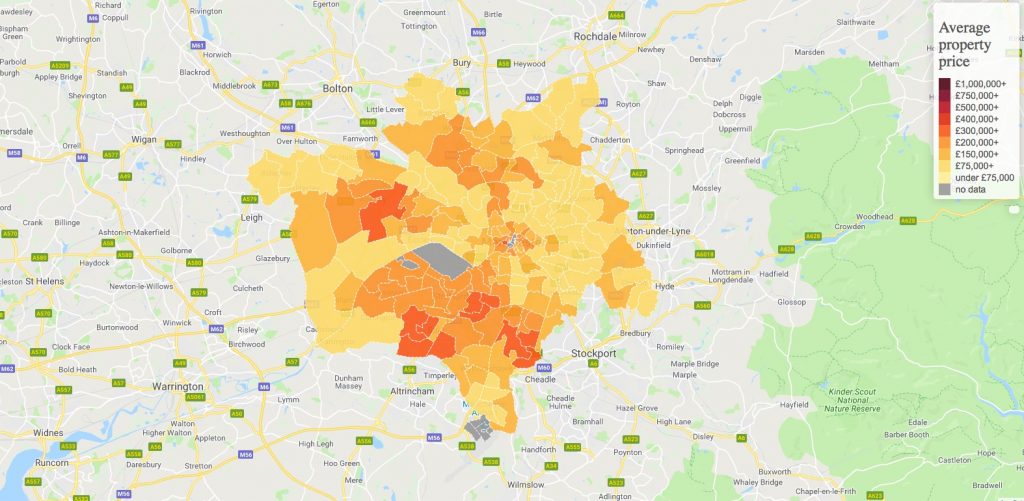

Average property prices in Greater Manchester (last six months). Data from HM Land Registry. Image from plumplot.co.uk (click to enlarge)

Supporting a growing economy whilst tackling homelessness

The challenge for Greater Manchester’s planners is to develop a housing strategy which supports its growing economy whilst simultaneously tackling the homelessness and deprivation which blight parts of the city. At one end of the market, there is a shortfall in the number of family homes for second and third-time buyers seeking larger properties for growing families, with many of these buyers moving out of the city-region altogether, to Cheshire, Lancashire, and the Peak District. At the other end of the spectrum, right-to-buy and restrictions on local councils borrowing to build have resulted in a shortage of social homes to rent, meaning most renters on low incomes are forced into expensive and often poor quality private rented accommodation. Across Greater Manchester, there are 80,000 people on social housing waiting lists.

Rocketing city centre property prices and concerns about gentrification are something of a distraction from these pressing issues. Central Manchester may increasingly resemble a London of the North, with its cranes, cat cafes and congested transport network, but the housing issues affecting Greater Manchester as a whole are very different to those facing the South East. The second draft of the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF), set for publication in June, is likely to see more focus on development in outer towns and boroughs and will provide some indication of how Mayor Andy Burnham and other city leaders see development policy evolving over coming years. Manchester city centre will continue to attract investment, and prices look set to rise further. It is beyond the Mancunian Way where the most intriguing development battles will be fought, and where the biggest impact on the lives of Manchester residents can be made.