Dr Ingrid Storm from The University of Manchester examines religiosity and attitudes to immigration in Europe. She found that religious conformity to the national average is associated with negative attitudes toward immigration.

- Religion does not predict immigration attitudes uniformly across countries.

- Those who belong to majority denominations are more likely to be concerned about immigration.

- In countries with low rates of church attendance, turnout was associated with pro-immigration attitudes, whereas in countries with high rates of attendance it was associated with anti-immigration.

- The association between religion and anti-immigration is strengthened in contexts of economic uncertainty.

Religion in immigration debates

Religion has been a prominent topic in debates about immigration and ethnic diversity in Europe over the past fifteen years. Muslims constitute a significant proportion of immigrants to in the majority Christian, or secular countries in Europe. This has led to concern about immigration’s consequences for national cultures, and to seemingly contradictory associations between Christianity and attitudes to immigration.

The Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán speaks of Hungary as a Christian nation, as an argument to reject EU’s refugee quotas, and similar arguments have been used in Poland and Austria. This echoes White Evangelical Christians in the US’ strong opposition to immigration and support for Trump. Closer to home, members of the Church of England were significantly more likely to vote for Brexit.

At the same time, many Christians, Pope Francis among them, argue that being tolerant and welcoming and offering shelter to those in need are among the religion’s core principles. A number of refugee charities are also run by churches and other religious organisations.

The purpose of this study was to find out under what cultural and economic contexts we can expect there to be a relationship between an individual’s religiosity and their attitudes to immigration. Previous research has shown that religion and immigration attitudes are related mainly when they can both be linked to national identities (Storm 2011a). Majority religious identities and behaviours could be a way of signalling belonging to a national community and distancing oneself from religious and ethnic minorities.

National religious context

In a recently published article in European Societies, I analysed data from seven waves of the European Social Survey (ESS), collected every two years over twelve years from 2002 to 2014. This data allowed me to examine the association between religion and immigration attitudes cross-nationally and over time, in what was a financially unstable period for many European countries and households. More than 300 000 individuals in 31 countries were asked whether they saw immigration as good or bad for the economy and whether they thought the country’s cultural life was undermined or enriched by immigration. They were also asked what religion they belong to (if any) and how often they attend religious services. By calculating the average religiosity across the country (and year) I was also able to measure the national religious context of each individual respondent.

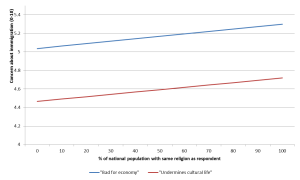

The main finding was that it was not individual religiosity in itself that was associated with anti-immigration, but the degree to which the individual’s religiosity conformed to the average religiosity in the country they lived. People who were Catholic in majority Catholic countries and Protestant in majority Protestant countries were more likely to have concerns about immigration, but so were nonreligious people in majority nonreligious countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Predicted immigration concerns by percentage same religion (or non-religion) as respondent

This was not only the case for religious affiliation, but also for religious practice. The higher the average level of religious service attendance in a country, the more regular attendance was associated with anti-immigration. In contrast, in countries where very few people attend services regularly, those who do were more likely to hold pro-immigration attitudes

Economic context

A further important finding was that the relationship between religious service attendance and immigration attitudes depends on the economic context. The higher the country’s GDP and employment levels, the less religious practice is associated with negative attitudes toward immigration. This supports previous research on the relationship between material insecurity and religious and national identity. Religion could appeal to economically insecure individuals by providing a coherent group identity and social and emotional support (Bradshaw and Ellison 2010; Storm 2017) and can take on a meaning of nationalism, ethnocentrism and other forms of in-group identity in situations of external threat (Kinnvall 2004)

Expression of national belonging

This research shows that religious identity and practice are associated with concerns about immigration in Europe, but that the effect of religion varies depending on both the religious and economic context. The relationship between religiosity and concerns about immigration can be expected to strengthen under two conditions.

- The first condition is that there is coherence between national and religious identity, in other words, that the individual’s religious affiliation and behaviour conforms to the national norms.

- The second condition is a situation of insecurity or perceived competition, for example, economic hardship or high rates of unemployment. This suggests that it is not religious beliefs or practices per se that are associated with anti-immigration, but religion as an expression of national belonging, conformity to social norm or conservative values.