There are long held assumptions that taking any job is better for a person’s health and wellbeing than being unemployed. A study of over 1000 unemployed adults by Tarani Chandola, Professor of Medical Sociology at The University of Manchester, compared health and stress levels of those remaining unemployed and different quality jobs. The study revealed evidence that runs contrary to these assumptions.

- Mental health outcomes of adults in poor-quality work are often no different to those who remain unemployed; yet those in good quality work see increases in their mental health;

- Health and wellbeing outcomes for people with two or more adverse job measures are worse than peers who remain unemployed;

- The importance of ensuring good quality work should be high on the government’s agenda following the publication of Matthew Taylor’s review of modern work practices.

There seems to be a common consensus that anything is better than being unemployed – even working in a job that does not pay well and in which you have little control over your working conditions, such as the hours that you work. Economists such as Lord Richard Layard have emphasised the need to get people out of unemployed states as “(almost) any job is better than no job”. There is good econometric evidence from following up cohorts of unemployed adults in the 1990s and 2000s which show low paid jobs are a spring board to better quality jobs later on in a person’s career. But even if that were true nowadays, and there is some reason to doubt whether job career trajectories are the same now as 20 years ago, it may still be the case that working in a terrible job does all sorts of negative things to your health and wellbeing right now. And although there is a lot of research showing just how bad it is for a person’s physical and mental health to work in a poor quality job compared to someone in a good quality job, most people assume at least the person in a terrible job is better off than someone unemployed.

Comparing stress response levels of adults in and out of employment

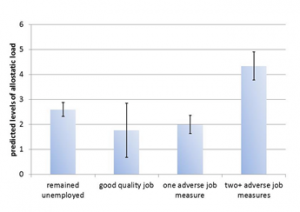

In this research paper, we directly tested this assumption and found evidence contrary to the common perception. We followed up a cohort of over 1000 unemployed adults who were representative of the population of unemployed adults living in the UK in 2009-10 and compared what happened to the health and stress levels of those who remained unemployed and those who got jobs of both good and poor quality. We measured a number of biological factors that correlate with normal and abnormal stress responses, known as the allostatic load index. We also measured job quality in terms of low pay, low job control, high insecurity, high dissatisfaction and high job related anxiety. We found that the improvements in mental health of formerly unemployed adults who became re-employed in poor quality work were not any different from their peers who remained unemployed. Unsurprisingly, those who found work in good quality jobs had a big improvement in their mental health. More significantly, as shown in the figure below, those who were working in poor quality work (two or more adverse job measures) actually had higher levels of allostatic load (chronic stress related biomarkers) than their peers who remained unemployed.

[Figure: Predicted levels of allostatic load (chronic stress related biomarker levels) by job quality/transition categories: Understanding Society waves 1-3]

Now it could be that maybe the unemployed adults who subsequently were employed in poor quality jobs had worse health and more stress at the start compared to their peers who remained unemployed. But this was actually not true. As many others have found, there are strong selection pressures into employment, and healthier people are much more likely to find work (any type of work, whether good or bad) than unhealthier people.

The need to “make all work good” a reality

With the publication of Matthew Taylor’s review of modern work practices , the importance of good quality work should be high on the government’s agenda. However, he, like many others, has said that the “worst work status for health is unemployment”. Our research shows that is not necessarily the case, and our findings, together with more research in this area, should be considered carefully as strategies are hopefully developed to make his call to “make all work good” a reality not a pipedream, especially in the current political climate.

The paper “Re-employment, job quality, health and allostatic load biomarkers: prospective evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study” by Tarani Chandola and Nan Zhang was published in the International Journal of Epidemiology, dyx150 .