Here Dr Sylvie Lomer explains why international students aren’t a visa risk and outlines how false assumptions have been used as justifications for migration policies that seriously prejudice and inconvenience international students.

- Recently published Home Office data shows that 97.4% of international students are compliant with visa regulations, contradicting previous statements from Government that 20% of students were ‘overstaying’

- Students staying longer than three years was understood to constitute abuse of the system but there are a number of perfectly legal scenarios in which students might stay longer than three years

- International students are among the most watched, checked-up on, and interrogated immigrant populations. Yet they are the most compliant.

Last Thursday, the Home Office published data – based on the recently re-introduced exit check data – which shows that 97.4% of international students are compliant with visa regulations. Some of the media coverage (at least based on what I heard on the Today Programme) seems to suggest surprise at the high levels of compliance.

Now, it’s understandable that this seems to contradict what the Government and the Conservative Party have been saying for the last seven years. There’s been a lot of talk of ‘20% of students overstaying’, ‘over a fifth of students stay longer than three years’, and this quickly became conflated with the imperative to ‘crack down on abuse of the visa system’. In other words, staying longer than three years was understood to constitute abuse of the system.

Except, of course, it doesn’t. There are a number of perfectly legal scenarios in which students might stay for longer than three years, all permitted by the current visa system. They could study English at a language college or pre-sessional course for a year before progressing to an undergraduate course: four years. They could be studying medicine: five years. They could progress from a language to undergraduate to postgraduate: five years. They could work as graduates for a year or two (if they can get through the stringent points-based system requirements): five years. And none of this is illegal, noncompliant or indeed a problem. We encourage it.

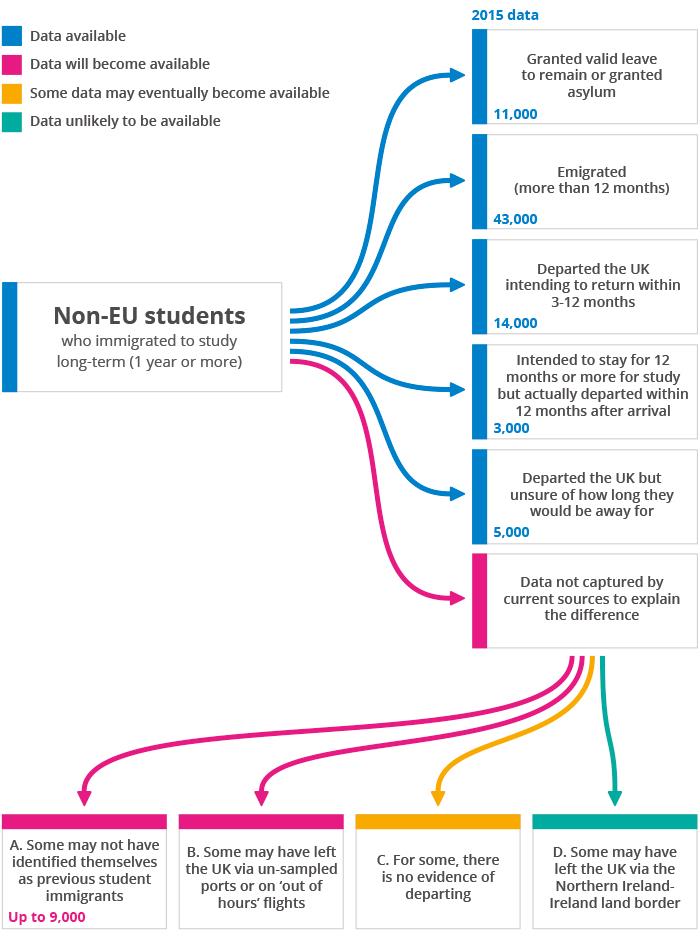

This is the Office of National Statistics’ depiction of all the entirely legal outcomes that might happen for a student, based on the International Passenger Survey (IPS).

Where has this figure come from? A 2010 study commissioned by the Home Office did a survey of international students who had initially been granted a student visa five years earlier. They found that 20% of these students were still in the UK – all of them entirely legally. In the context of 2010 election, this figure got picked up as evidence that there was a problem ‘controlling the migration system’. Theresa May, as Home Secretary, called it “unchecked permanent migration through the back door”. David Cameron called it evidence that “many gain temporary entry into the UK with no plans to leave.” Immigration Minister Damien Green considered evidence of a migration system that was “out of control”. It also coincided with the bogus college scandal, suggesting that there were a number of institutions and students intentionally abusing the system.

That’s been made worse in the last couple of years by mis-used data from the ONS, which published findings that approximately 84,000 students fell into a ‘gap’ between the numbers of students arriving and the number leaving. This got reported as ‘100,000 foreign students living illegally in Britain’. In fact, it was largely attributable to methodological issues with the International Passenger Survey. Basically, it consistently under-sampled international students, partly because it didn’t sample anyone leaving between 10pm and 6am, and partly because it asks about ‘migration intentions’. That means if graduates are returning on a work visa, they may not identify themselves as former students, for instance, and students may change their plans after taking the survey. Also, we’ve known this for a while. The ONS hasn’t made false claims about what the IPS can and can’t do.

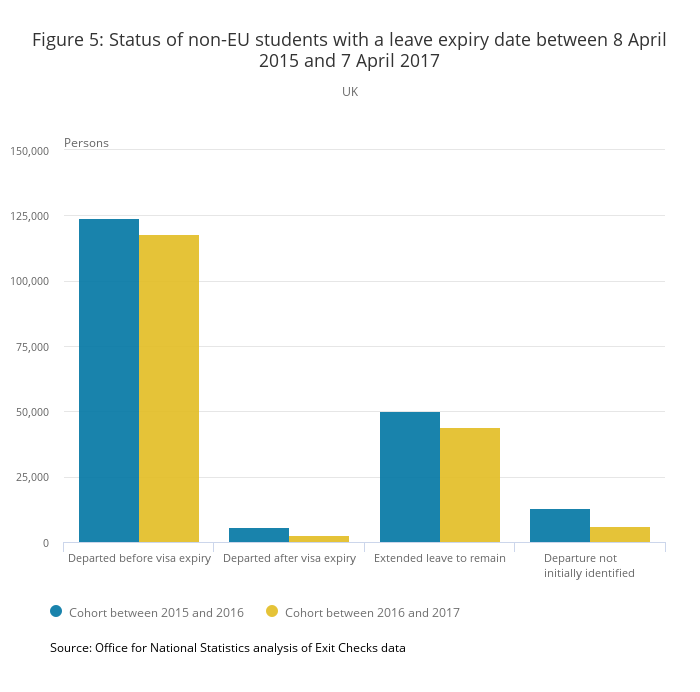

The analysis of the exit check data sorts this gap out, reducing it to 3% or 4000. The ONS analysis is clear that this gap does not mean these 4000 students are illegally living in Britain: it means the data couldn’t be conclusively matched. The Home Office report explains that there are a small proportion of ‘uncertainties’ within the immigration system which might generate this lack of information.

So it’s completely compatible to say both ‘a fifth of students stay over 5 years’ and 97% of students are compliant with their visa regulations. Both the ‘overstay data’ (a really misleading shorthand that needs to be stepped on) and the ‘student gap’ have been used as justification for migration policies that seriously prejudice and inconvenience international students.

Let me give you a few examples.

- The health care levy. Not content with the fees they pay, the fact that many have private health care insurance, or that they make contributions to local communities, international students like all immigrants have to pay an annual £250 fee to cover their potential health care costs.

- The landlord provision. Landlords are now required to check the immigration status of tenants.

- Police registration. This antiquated tradition requires students from selected countries to pay yet another fee to sign a piece of paper at the police station. It’s not clear why, what for, or what benefit this has ever afforded. Many students resent this additional piece of bureaucracy, which frequently takes them out of class during the first week of their studies as they are given an immovable appointment.

- Biometric visa requirements. Having fingerprints taken at approved centres means for some students flying to another country, and for others extensive travels (UKCISA, 2011).

- The cost of visas. Applying costs £364, plus cost of travel. Extending a visa or switching costs over £400. Additional costs include: translating documents, attending biometric appointments, couriering documents, premium phone line costs, English language test fees, paying for agents to help navigate unclear regulations. Some students reported the application process costing them in total over £2000 (UKCISA, 2011).

- Limitations on graduate work. This is complex, so I’ll leave it at this: since 2012, it’s been made much more complex and challenging to get permission for graduates to work.

So international students are among the most surveilled, checked-up on, and interrogated immigrant populations. Yet they are the most compliant. At some point, the Government might consider that its industrial strategy for international education which ‘predicts’ a rise in international students, which depends on the reputation of the UK as a destination for excellent education in a safe and welcoming environment, might be in contradiction with certain of their immigration policies.

And as for the Home Secretary’s launch of a ‘probe’ into ‘the contributions of international students’, well, it’s a nice gentle lead-in to a long overdue u-turn (conditional on May’s approval). But let’s save her the trouble. Here’s a snapshot of data on their impact:

- International students bring in more than £25 billion (Universities UK, 2017)

- ‘the long-term fiscal benefit is likely to be positive’ (University of Sheffield, 2014)

- UK students value international students’ presence in universities (British Council report)

- The UK gains political influence as a result of hosting international students (BIS Research Paper 128)

- Total education exports estimated to be £14.1 billion in 2008/09 (BIS Research Paper 46)

- International students help sustain the UK’s research base in STEM (UKCISA briefing)

We know this. No one else is surprised by this, and nor is the Government. International students have been a great punching bag for the immigration debate, a nice soft easy compliant target. So if it takes another piece of research to show the major economic, social, cultural and educational benefits of international students, fine. But let’s not hang about, because it’s been almost a decade of this hostile policymaking, and it’s starting to cost us.