An important indicator of a breakdown of barriers between different ethnic groups is accepting someone of a different ethnic background marrying into the family. Much research into attitudes looks at the views of the majority ethnic group separately to those of the minorities. In a break from this tradition, researchers from the University of Manchester looked at the social attitudes of white and non-white British residents. Here, Dr Ingrid Storm explains that while their findings suggest a positive trend, they can also be read as a warning.

• There is a general increase in the proportion of ethnic minorities in Britain who would welcome a close family member marrying a white person.

• This mirrors the trend of increased white British acceptance of ethnic minority in-laws.

• Those who are born or long-time resident in the UK are most positive.

• Experience of discrimination leads to social distance.

Changing attitudes

A number of reports, the latest by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) show a dramatic increase in racist hate crimes and discrimination of minorities after the Brexit vote. Many now fear heightened tensions and increased separation between ethnic groups in Britain. Recently published research by myself and colleagues Maria Sobolewska and Rob Ford, shows that both white and ethnic minority Britons have generally become increasingly accepting of interethnic marriages in their own family. However, ethnic minority people who have experienced rejection by the white British express greater distance from them. This research shows that discrimination, in addition to leading to unequal economic opportunities, can also have more subtle effects on social attitudes and family relationships.

Since the early 1980s, The British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey has asked white British people how they would react if a close relative were to marry someone who was Black or Asian. We have previously blogged about this research, focusing on the increased acceptance of potential ethnic minority in-laws among younger generations, and why we find particularly negative attitudes to Muslims.

A two-way street

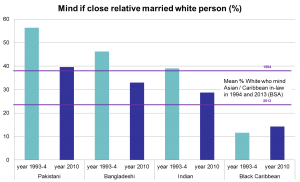

But interethnic marriage is a two-way street. Here, we focus on the other side of the issue: the attitudes of ethnic minorities towards welcoming whites into their families. In two surveys (the Fourth national survey of Ethnic minorities from 1993-94 and the Ethnic Minority British Election Survey from 2010) a large sample of ethnic minority respondents were asked if they would mind if one of their close relatives married a white person. We found that in general the ethnic minorities have become more positive towards whites.

Figure 1:

4th National Survey of Ethnic Minorities 1993-4 / Ethnic Minority British Election Survey 2010, compared to the British Social Attitudes Survey (BSA) in 1994 and 2013.

For three out of four groups, opposition to a white in-law declined between 1994 and 2010 (see Figure 1). The exception is black Caribbeans, who already had a favourable view of intermarriage with whites in 1994, when only 12 per cent expressed opposition to it. This is notably lower than the 39 per cent of whites who said they opposed their family members marrying a black Caribbean in the same year (BSA 1994). The particularly negative views about intermarriage with Muslims found among whites is mirrored in the views of Muslim minorities themselves – the highest opposition to intermarriage with whites is found in the predominantly Muslim Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups.

Unlike the white majority’s attitudes, the change in ethnic minorities’ views cannot be attributed to differences between older and younger generations, nor to changes in education. What does make a big difference is how long the respondent has been in the UK. Those who are born in the UK are more likely than first generation immigrants to accept white in-laws, and the immigrants who have lived in the UK for a longer period are more tolerant of ethnic intermarriage than recent arrivals. Rates of actual interethnic marriage show a similar pattern – they are considerably higher for the UK-born minorities of all ethnic groups (Muttarak and Heath 2010). This suggests that attitudes to intermarriage are, in part, based on experience of and contact with the white majority.

The impact of negative experience

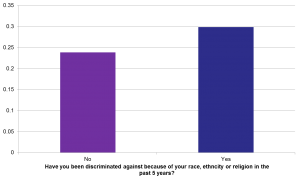

But contact with the majority could also have less positive consequences: Minority respondents who have experienced discrimination on the basis of their race, ethnicity or religion in the past five years are more opposed to marriage with the white majority by six percentage point.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of minding if relative marries white person by experienced discrimination

Ethnic Minority British Election Survey 2010

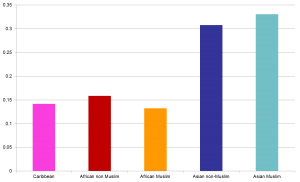

Once we take personal experience of discrimination and socio-demographic factors into account, the views of Asian and African Muslims are no different to those of non-Muslims with the same ethnic origin (See Figure 3). In other words, we do not find evidence that Muslim minorities, who as a group, are on the receiving end of more hostile attitudes, react by becoming more hostile unless they have recent personal experience of discrimination.

Figure 3: Predicted probability of minding if relative marries white person by ethnic/religious groups

Ethnic Minority British Election Survey 2010

Direct social experience clearly matters for ethnic minorities. Those born in Britain, who have more extensive contact with the majority group, report much lower social distance, but those who report experience of discrimination report greater social distance.

Far-reaching consequences

While this research suggests a generally positive trend, whereby acceptance is gradually overcoming ethnic prejudice, it can also be read as a warning about the vulnerability of ethnic relations. While much has happened in British society since 2010, when the data used for this analysis was collected, there is no reason to believe that the relationship between discrimination and interethnic social distance has changed. Repeated negative experiences of the behaviour and attitudes of the majority ethnic group is likely to result in more fear, isolation and scepticism among minorities. On the flipside, ensuring that people are protected from ethnic discrimination and hate crimes could have far-reaching positive social consequences beyond the affected individuals’ lives.

In times of political and economic uncertainty we must take special care not to undo the positive increase in acceptance amongst all ethnic groups that the UK has been achieved.

• Is ethnic prejudice declining in Britain? Change in social distance attitudes among ethnic majority and minority Britons by Dr Ingrid Storm, Maria Sobolewska and Robert Ford was recently published in the British Journal of Sociology