Dr Ingrid Storm from The University of Manchester finds that people who live in countries with lower GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and lower social welfare spending are more religious on average. This is in part because religiosity can act as an alternative form of social security when government welfare is not available. The results have been recently published in Sociology of Religion.

- There is a link between lower welfare spending and higher levels of religious participation

- Religion declines with economic growth and security

- Participation in a religious community can act as social insurance which could alleviate the absence or reduction of a state support system

As reported in the Guardian, the UK was the only rich EU country to cut welfare spending as a proportion of GDP between 2011 and 2014. The austerity policy has already had consequences for religious and other community organisations that have been stepping in to fill the void, by setting up foodbanks and other initiatives. But could such economic changes also have consequences for individual religious participation?

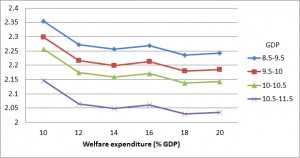

Using data from the European Social Survey, a study of 31 European countries over a 12 year period from 2002 to 2014, I found that between countries and over time, more welfare spending is associated with lower religiosity. As Figure 1 shows, religion decreases as welfare expenditure increases, at each level of GDP. Further, within countries, people with lower household income are more likely to be religious and more likely to attend religious services regularly.

One of the main puzzles in the Sociology of Religion is why religion declines in some countries while it persists and even increases in others. One explanation that has gained currency is that religion increases in situations of conflict and unpredictability, and declines in contexts when people feel secure about their continued survival and prosperity.

Some scholars argue that not only does insecurity increase religion, but religion also reduces the negative effects of insecurity and stress. People in insecure economic conditions may adopt religious beliefs and practices because they provide relief from adversity. There are two possible ways this could happen.

Reasons for participation

Firstly, religious participation in a community could provide social insurance through networks and access to funds and services, as well as pastoral care, particularly when other options are not available. Secondly, it is possible that religious beliefs could be a useful psychological coping mechanism. Previous research on panel data has found that religious people suffer less economic and psychological harm than nonreligious people from economic crises, marital separation and natural disasters. This has been called the “religious buffer effect.”

In this study, it was found that religious people were more likely to be satisfied with their country’s economy compared to nonreligious people in the same country. Further, regular church attenders were less likely to think it difficult to get by on their income than non-attenders on the same household income.

The “buffer effect” was better measured by how often people attend religious services than how religious they would describe themselves as. This indicates that it is active participation in a community, rather than privately held beliefs, that matter for coping with the negative effects of economic insecurity.

Social insurance

Our findings support the theory that participation in a religious community can act as social insurance which could alleviate the absence or reduction of a state welfare system.

This may be particularly important in places where a large proportion of the population is already religious, but not actively practising. In such contexts, economic downturns and cuts to welfare budgets could increase religious participation, and could be an opportunity for religious organisations to recruit new members.

The government has actively sought to engage faith-based organisations, in order to relieve the state of providing particular services and strengthening local communities. However, while religious activity does seem to provide stress relief it is worth asking whether faith-based organisations should be privileged as contractors in a country where each generation is less religious than the previous one.

Applications for the society

In an increasingly secular culture such as Britain, it seems unlikely that people would take up religious beliefs and practices in large numbers. However, this research may have applications for other parts of the third sector and community organisations. Finding out what it is about religious practice that is effective and supporting and using those elements for other community and grassroots activities could increase social support and well-being among people who struggle economically.

More fundamentally, this research indicates that welfare spending and economic security reduces the need for religious activity altogether, even if it does not reduce civic activity more generally. To promote a healthy civil society where people take part in social and religious activities because they want to rather than because they need to, austerity policies are unlikely to be the solution.

Figure 1: Predicted Religious Service attendance (1-4) by GDP and welfare expenditure

European Social Survey 2002-2012