Guest edited by Ben Pringle, former chair of Post Crash Economics

Geoff Tily’s contribution about the contrasts of trade and finance globalisation demonstrate his knowledge on the misconceptions of Keynesian economics, for which his work on is highly regarded. Here, in the final Davos Takeover series, Geoff looks back at economic policy over the years and questions has globalisation already ground to a halt?

- Free trade may have been a constant of post-war policy, but not for finance

- The 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement permitted countries to put in place or keep in place capital controls

- In the 1970s restrictions on domestic credit creation were removed, fiscal retrenchment began and capital controls were dismantled

- Financial globalisation coincided with a very material change for the worse which coincided with a material decline in domestic demand

Top of the agenda at Davos are the threats to globalisation. But has globalisation already ground to a halt? In September 2016 the OECD showed a measure of world trade at its lowest point for thirty years.

As trade deals dominate much political rhetoric, it’s easy to miss that the flows of goods and services are not the whole story of globalisation. The other side of the story is flows of finance and, in particular, the ability of the owners of wealth to move their money (or ‘capital’) across international borders. Free trade may have been a constant of post-war policy, but this has been far from true for finance; it is increasingly obvious that the interests of the trade side of globalisation can be different to those of the finance side of globalisation.

Finance as servant to the post-war world

The world emerged from the Second World War with a renewed philosophy towards international finance. This approach originated in the failure of the gold standard regime, which opened (‘liberalised’) borders to international capital. A credit-fuelled boom gave way to bust and the greatest global slump in history. The conclusion that the liberal regime had failed the world economy and was dangerously opposed to the prosperity and stability of nations could not be avoided.

Towards the end of the war at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, policymakers aimed to devise a different order, with finance as servant rather than master of the economy.

This regime was aimed at permitting countries the autonomy to aim domestic economic policy at full employment. Most important was allowing countries the ability to set low long-term interest rates in order to foster high private investment and a substantial role for government spending. Thus the Bretton Woods Agreement permitted countries to put in place or keep in place capital controls. Although it’s worth remembering that it did not permit the fully elastic supply of international currency that Keynes had wanted – and later the system relied on the support of the Marshall plan.

This emphasis on domestic expansion was the reverse of the classical doctrine that prosperity is fostered through external trade. This doesn’t mean the approach was protectionist; quite the contrary:

“… if nations can learn to provide themselves with full employment by their domestic policy … there need be no important economic forces calculated to set the interest of one country against that of its neighbours … International trade would cease to be what it is, namely, a desperate expedient to maintain employment at home by forcing sales on foreign markets and restricting purchases, which, if successful, will merely shift the problem of unemployment to the neighbour which is worsted in the struggle, but a willing and unimpeded exchange of goods and services in conditions of mutual advantage.” (Keynes’ General Theory, Chapter 24)

Finance strikes back

But this settlement and philosophy didn’t last. From its creation in 1961 the OECD promoted the liberalisation of financial markets and the removal of capital controls, and the same became true of parallel initiatives towards European Monetary Union. In an excellent history on post-war capital controls, the IMF pinpoint the US U-Turn in the Economic Report of the President for 1973:

“controls on capital transactions for balance-of-payments purposes should not be encouraged and certainly not required in lieu of other measures of adjustment, nor should they become the means of maintaining an undervalued or overvalued exchange rate.”

Under the new US doctrine, the Bretton Woods position on capital control was regarded as a ‘bias’, inconsistent with the trade position. The IMF continue (and emphasise):

“Accordingly, when the text of the amended IMF Articles of Agreement was being negotiated in 1978, the US delegation managed to insert the phrase “the essential purpose of the international monetary system is to provide a framework that facilitates the exchange of goods, services, and capital among countries.”

From this point, the post-war philosophy was decisively reversed. From the start of the 1970s the international exchange and monetary regime devised at Bretton Woods was ended; restrictions on domestic credit creation were removed; fiscal retrenchment began and capital controls were dismantled: a process of financial liberalisation was set in motion. It has endured to this day.

Yet from our current standpoint, it is very far from obvious that the liberalised regime has served the global economy well. In retrospect the post-war years saw unrivalled prosperity, exemplified by the idea of a ‘golden age’. Financial globalisation coincided with a very material change for the worse.

Evidence: domestic demand

This change for the worse coincided with a material decline in domestic demand, and in particular the strength of investment and government spending.

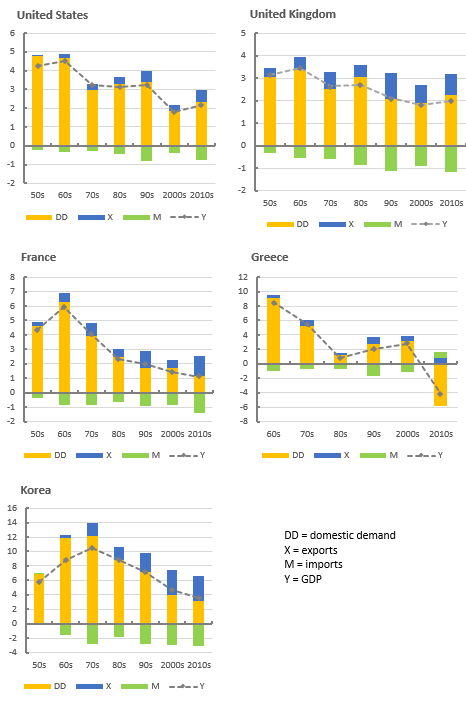

This is easily illustrated by looking at the decomposition of economic growth since the Second World War. The charts below show annual average growth by decade for various countries. (The source is the invaluable OECD National Accounts database; the curious group of countries chosen are those with the most extensive historical data.)

Plainly strong GDP growth in earlier decades was dominated by strong domestic demand; weak growth in later decades then followed weak domestic demand. While exports have become more important over time for most countries, this has not compensated for the shortfall in domestic demand. Imports have also increased in parallel and so the benefit from net trade has been relatively negligible.

Trade and domestic demand: annual average growth and contributions (ppts) by decade

Obviously there are exceptions: in Greece the positive contribution from imports in the latest decade reflects the catastrophic decline in domestic demand as a result of the severity of austerity; Korea has seemingly been more successful in re-orienting to exports.

Evidence: Trade

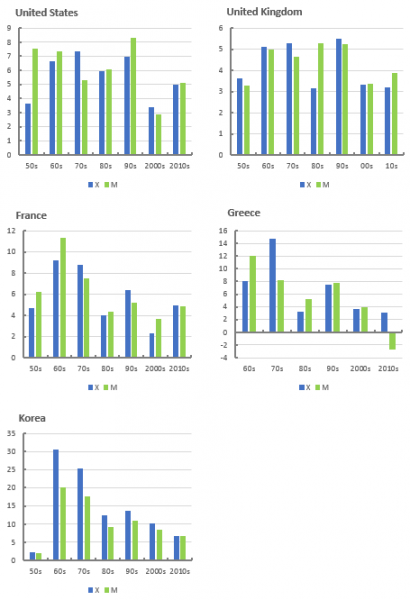

The charts below show average annual growth of exports and imports by decade. From the 1980s onwards, export growth is not only greatly reduced but also more volatile. Exports may have been more important to the weaker growth of recent decades (as on the first set of charts), but trade was in fact stronger in earlier decades.

Export and import growth, annual average by decade

Everything is upside down: trading relations have been weaker in the period associated with globalisation and stronger over the decades when globalisation was regarded as in its infancy. According to the post-war philosophy, this was wholly predictable.

Why all this matters now

Beyond the abstract world of economic statistics, the scale of hardship and consequent disaffection is now widely understood. Progressive debate seems to have got stuck at the point of seeking ways to compensate globalisation’s ‘losers’ . But there are rays of hope. In their review, the IMF were candid enough to report the previous US philosophy around capital control, citing Robert Helleiner (a respected and radical commentator on trends in international finance):

Helleiner (1994) notes that the measures reflected scepticism among US policy makers concerning the benefits of a liberal financial order:

“The 1967 Economic Report of the President, for example, justified capital controls on the grounds that financial flows were not producing an optimum distribution of the world’s scarce capital but rather were responses to differences in national monetary policies, taxation, financial structures, and cyclical economic trends. Even the American Bankers Association was forced to admit in 1968 that the case for free capital movements was weak, given that many such movements were speculative, unproductive, and tax-avoiding.”

Exactly 50 years after the 1967 Report, the validity of this analysis is incontestable. It is moreover apt that it is the IMF that is saying it – their existence is owed to the post-war settlement (even if some might regard their subsequent record as mixed).

The question is – is anybody listening?