Guest edited by Ben Pringle, former chair of Post Crash Economics

Andy Ross is someone who I admire due to, not only his work within the Government Economic Service & the HM Treasury, but also because of the economic insight he provides. His blog here is extremely important, focusing on simply economics and ignoring other factors such as politics. Going forward economists need to be well versed in not just economics, but in the real world.

- Economists cannot work in a vacuum, ignoring other approaches limits both the quality of thought and breadth of application

- Concepts such as social & natural capital, and the costs of social discontent, must be worked into economic research models to remain relevant

- The ‘Rethinking Economics’ movement should prompt us to rethink ‘economists’; their role, reach and purpose

A recent article in the Economist magazine argued that it is dangerous to leave politics out of economic policy formulation, as political impacts can in time eclipse the relevance of the economics.

“Many economists shy away from such questions, happy to treat politics, like physics, as something that is economically important but fundamentally the business of other fields. But when ignoring those fields makes economic-policy recommendations irrelevant, broadening the scope of inquiry within the profession becomes essential.”

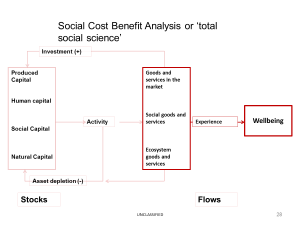

Quiet so, and the social researchers and economists working together in the UK government’s Department for the Environment Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) recently published a simple but conceptually rigorous framework on this. The framework shows why other disciplines are needed for a deep understanding of even the economists’ own familiar identity that ‘Income equals Return multiplied by Capital’ i.e. production depends on capital, and productivity.

In the DEFRA diagram the three big boxes represent from left to right: Capital, Return and Income. We are not even close to an operational version of the framework, indeed it could never be precisely calibrated, but it highlights the major gaps in how economic policy is usually formulated, gaps that rounded policy makers appreciate are as important as, or more important than, economics.

To the usual economic categories of capital, i.e. produced (e.g. machines and physical infra-structure) and human capital (education and skills), must be added both social and natural capital. Natural capital comprises ecosystem services that natural assets provide, including soil, air, water and living things. So, if the volume of produced capital increases at the expense of natural capital then this could lead to a reduction in production. This could be a reduction in GDP, but as the DEFRA framework highlights GDP is only part, albeit an important part, of what contributes to well-being.

To the usual economic categories of capital, i.e. produced (e.g. machines and physical infra-structure) and human capital (education and skills), must be added both social and natural capital. Natural capital comprises ecosystem services that natural assets provide, including soil, air, water and living things. So, if the volume of produced capital increases at the expense of natural capital then this could lead to a reduction in production. This could be a reduction in GDP, but as the DEFRA framework highlights GDP is only part, albeit an important part, of what contributes to well-being.

The work of great modern economists such as Lord (Nicholas) Stern has done much to integrate natural capital into modern economics. Social capital, the stock of social networks, shared norms values and understandings that facilitate cooperation within or among groups, was emphasised by great historical economists, including Adam Smith, but remains far less integrated. Today, non-economists listening to discussions of economic policy are often dismayed that while a great deal is said about sovereign default risks (adverse market reaction risk, inflation or deflation risks and perhaps unemployment risks) social capital and societal discontent risks are usually ignored.

Most economists regard it as idealistic, impractical or beyond their brief to consider social capital and societal risks when setting economic policy. However, recent experiences have vividly reminded us of the dangers from the political feedbacks that flow from the destruction of social capital. Even if, for the sake of argument, ‘austerity’ did work effectively to reassure market-makers and reduce sovereign risk and interest rates etc. these risks should have been balanced with the risks that may arise from increased discontent among aggrieved sections of the population hit by spending cuts.

Growth in GDP while large sections of the electorate are left behind sows the seeds for future crises. Events such as BREXIT and the rise of the far right in liberal democracies show the dangers of fuelling populist politics through neglecting social capital. In the 1930’s such political turmoil led to nationalism, economic dislocation and protectionism, and hence to the Great Depression. All feedbacks that dominated and eclipsed economic policy just as they are threatening to do so today.

Recently a ‘revolt’ by university students at The University of Manchester led to the ‘Rethinking Economics’ movement, a powerful call for pluralism against the narrowness of modern economics. While it is easy to criticise this as young idealism, experience reveals how problematic it is to operationalise elusive concepts that are immeasurable in any precise way. In my view the students were right and many more seasoned and eminent economists have backed their call. In the real world policy-makers must make judgements about many wider things that we cannot know with precision. All the important trade-offs affected by economic policy must be factored in to the best of our judgement if we are to avoid making matters worse instead of better. In short, the lesson we must relearn is that economic policy makers ignore other disciplines at all our perils; too often to be only an economist is simply to be a bad economist.