Last week, policy@manchester hosted a roundtable on productivity with representatives from HM Treasury, Greater Manchester Combined Authority and academics from The University of Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds. Here, Professor Diane Coyle reflects on the discussion and lays out her views on what needs to be done to boost the UK’s economic productivity.

- If the pre-financial crisis trend had continued since, the level of UK GDP per hour would be 17% higher than it is now

- In Greater Manchester, the most rapid growth in employment has occurred within low paid, low productivity sectors

- The May government has identified the need for an industrial strategy with a discussion document expected in the spring

- We need to rethink the relationship between public and private sector to bring about an improvement in the UK’s productivity performance

Why has the UK economy’s productivity, or output per hour worked, flatlined for the past 10 years? The question matters because the ever-more efficient use of the resources available in the economy is the only thing that drives living standards higher in the long run. Everything from better health to more energy–efficient cars and buildings, to greater material comfort depends on the innovations and processes reflected in the productivity figures.

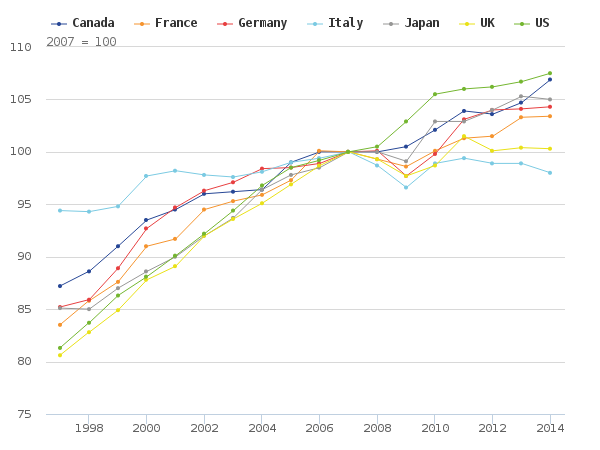

Last week, policy@manchester hosted a workshop on this issue, which has come to dominate economic policy debate. It involved members of the UK Treasury’s productivity team, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority policy team, and academics from Sheffield and Leeds, as well as the University of Manchester. The discussion started with an analysis of the nature of the problem. While all the G7 major economies have experienced slower productivity growth since around 2006 (see chart), the slowdown has been more marked in the UK, which also has a lower level of productivity than many similar countries. If the pre-financial crisis trend had continued since, the level of GDP per hour would be 17% higher than it is now. This is an enormous shortfall, given how quickly small differences in growth compound into lost potential improvements in living standards.

Looking within Greater Manchester, the region has lagged the average UK productivity performance back to at least 1991. There are more low skilled, low paid jobs than elsewhere in the country, and the most rapid growth in employment has occurred within low paid, low productivity service sectors. There is also a concern about the distribution of economic growth and opportunities within Greater Manchester.

One possible clue to the productivity puzzle is the decline of some high GDP/hour sectors – notably oil and financial services. There has also in general been a shift in the composition of the economy away from manufactured goods toward services, and within services toward those where either it is hard to increase productivity (such as health and education) or hard to measure it (including some professional services or digital, where there are questions about how well that intangible activity is captured by current statistics).

Turning to the drivers or productivity, the discussion touched on four key areas:

- The importance of social investment for productivity, long-term programmes linked to the needs of specific areas where employment levels and skills are low

- The need to focus not just on workers’ skills but also on how employers use those skills to make workplaces productive

- The role of the entire institutional framework for science-based firms, for example so that problems are owned, regulations do not make people over-cautious, public procurement is used intelligently

- The need to correct the UK’s significant under-investment over decades in infrastructure, with a focus on what services infrastructure provides to the economy

As these points underline, there is not going to be a quick fix to complex and deep-rooted structural weaknesses of the economy. What’s more, the fact that all countries have experienced some degree of slowdown in productivity growth indicates that reversing it will probably lie beyond the capacity of any individual nation. However, given that the UK has gone from looking more like the dynamic, technology-rich US economy to looking more like the structurally flawed Italian one, there is plenty of scope for domestic policy reforms.

Clearly, the measures repeatedly tried by various governments so far, such as investment in science and tax credits for research and development, have not made enough of a difference to productivity. Looking at the disappointing economic performance, the May government itself has identified the need for an industrial strategy, and is due to produce a discussion document on this in the spring.

A generation of UK politicians and officials have been allergic to the idea of any state involvement in innovation and industry, which was usually dismissed as ‘picking winners’ with the implication that the state was all too often backing losers. The time has come to rethink the relationship between public and private sector, not in the simplistic sense of state backing for specific technologies, but in terms of the framework of economic and political institutions that can help an economy thrive rather than stagnate.