The Indian Government recently caused uproar by announcing that the two largest denomination bank notes would no longer be legal tender. The aim was to tackle corruption and crime, but the sudden move also caused huge disruption to daily life and pandemonium at the banks. Indranil Dutta of the University of Manchester and Ajit Mishra, of the University of Bath, argue that the move might be unnecessarily damaging and urge caution against using monetary policy to combat corruption:

- The scale of demonetisation is unprecedented; some reports state almost 80% of all available cash is being withdrawn.

- Politically, the policy is being sold as a way to flush out corruption.

- Cash or coins do not create incentives- they are just a medium of exchange or store of value.

- The same forces of corruption that demonetisation is targeted towards can derail the expected outcomes from demonetisation.

- The government needs to undertake a multi-pronged strategy which includes tax reforms, campaign finance reforms, and speedy and strict enforcement of laws against corruption.

On 8th November 2016, India announced that two of its largest denomination of currency, the Rs 500 (£6 GBP) and Rs 1000 (£12 GBP) note, were no longer legal tender. The motivation for the demonetisation offered by India’s central bank, Reserve Bank of India (RBI), is the following:

“The incidence of fake Indian currency notes in higher denomination has increased. … High denomination notes have been misused by terrorists and for hoarding black money. India remains a cash based economy hence the circulation of fake Indian currency notes continues to be a menace.”

Given the 1.3 billion population of India, the scale of demonetisation is unprecedented. According to some reports almost 80% of available cash is being withdrawn creating severe shortages of cash. People have been given 50 days to deposit their money at the banks; and anyone depositing over a certain amount (more than Rs. 250000 or £2900 GBP) would be investigated by the tax authorities. Interestingly, the withdrawn notes are being replaced with a new higher denomination currency of Rs.2000 (£24).

Size of the black economy

On first reading it may seem that the policy would indeed tackle the problem of black money by flushing it out. The presumption being that a substantial portion of unaccounted income or wealth is held in cash and that too in big denominations.

To get an idea of the problem, a World Bank report showed that India’s shadow economy was around 28% of the GDP in the 2000’s, however a more recent report points to around 20% in 2015. Typically, black money is fuelled into assets such as land, buildings and jewellery, though cash is often used in large amounts to facilitate the acquisition of such assets. Black money acts as a lubricant (like any medium of exchange) for this parallel economy, so flushing out or extinguishing black money can potentially dent the shadow economy in the short run, without addressing the underlying causes. Further, this short run focused intervention is associated with high cost.

The role of cash

With India being a predominantly cash economy, one can argue that it is easy to carry out illegal activities (tax evasion, bribery, criminal activities, terrorist activities) with no fear of detection. While there is some truth here, corruption, weak enforcement and ill-designed policies are the key determinants of the shadow economy. Cash or coins, however, do not create incentives- they are just a medium of exchange or a store of value. The same forces of corruption that demonetisation is planning to curtail can derail the expected outcomes from demonetisation by having proxy exchanges, fake accounts, wrong labelling of income sources to take advantage of tax laws. So the benefits are likely to be less than what is being expected.

On the other hand, the cash-based nature of the economy also means that the costs are likely to be large. Rural as well as the informal sectors rely on high volumes of cash to carry out transactions for mostly legal activities. What we know is that financial inclusion is quite poor in India. Although it has increased sharply in the last two years, only 65 % of Indian adults have bank accounts. Thus close to 500 million people are without any bank accounts.

More importantly, only a little over 40% of the adult population are active bank users. So even with bank accounts, people prefer to deal with cash. The problem is worse for the poor, where only 46% of the bottom 40% of the population has a bank account. Given that it’s mainly the poor and illiterate who are really operating outside the formal financial sector, they are the ones who are going to get hit hard the most.

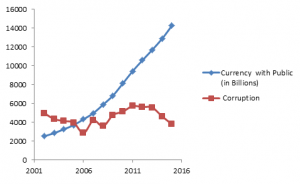

The size of the cash economy has no relation to the level of corruption. Below is the plot of average annual supply of currency with the public and an appropriately scaled corruption index for India (from the Worldwide Governance Indicators) from 2002 to 2015. As is evident in the graph, while there has been a rapid increase in the currency available with the public, corruption has remained quite steady and in fact has a slight downward trend in the last couple of years. What it highlights is that there might be other important drivers for corruption which are different from that of availability of cash in the economy.

Has the timing been right?

For the Government, this comes as a major shakeup after what most would call a lack lustre first couple of years. But, this is no time to destabilise the growth process by subjecting the economy to unnecessary risks. The way the stock market and money markets have reacted in the past weeks is indicative of the risks that lie ahead. In terms of exchange rates the Rupee has hit its lowest against the US Dollar in recent times. Moreover, in terms of minimising transactions costs and disruptions, this may not be ideal time because farmers are in between the two cropping seasons (Rabi and Kharif) and if the currency shortages continue, agricultural and related activities would be badly hit.

Implementation of the policy

While the shock and secrecy of the policy had a dramatic effect, the implementation has been a failure. What should have involved extensive effort in terms of banks’ preparedness, calibration of ATM’s, use of mobile ATMs, and clear policies regarding the amount of exchange and measures to prevent fraud is being done on the go. Many argue that the shock was necessary because any leak would have led to hoarders using their cash to buy gold and real estate assets. While this is a possibility, this assumes that the sellers of gold and other assets can somehow make use of these high denomination notes which are going to be discontinued. In any case, why worry about redistribution of black money?

It is also not clear if the intention was to flush out black money, why the tax amnesty wasn’t extended to include the current phase. As things stand, given the threat of prosecution, those with huge potential of earning black money, will accept a one-time loss and not deposit the money at all to avoid coming to the attention of the tax authorities. Also the issuance of higher denomination currency will retain the incentive to hoard cash in the future.

While the tax base may increase temporarily, it is not going to be a permanent increase. The overall deficit this year may come down, due to increased tax collection but there is also a good possibility of a contraction thus dampening the overall impact on tax receipts. Similarly, the impact on inflation will also depend on how remonetisation works and to what extent the deposits are used to extend credit. The fall in Rupee will also have an impact on prices and economic activities. There has been no clear indication, whether the RBI has thought about the possible scenarios and it’s plans to combat them.

Will this work?

This has become a political issue with arguments on both sides faulting on economic logic. Opponents of the policy would point out that this policy will reduce real estate prices and discourage investment in this sector and may affect growth. It is well known that real estate transactions involve substantial amount of cash and any move to control this black money would dampen prices and this should not be used as an argument against tackling black money.

Supporters argue that demonetisation would lead to lower crimes as typically these are paid through black market. In the informal and underground economy other payment mechanisms (such as deferred payments, third party guarantee etc.) can be used to overcome the temporary lack of cash. However, one needs to think whether monetary policy, with such “externalities” is the right policy to tackle crimes.

The point here is not to argue against any policy to fight tax evasion, black money and corruption. Rather, we want to see a more broad effort to tackle these issues with smart policies with little “negative externalities” and transactional costs especially when these costs are likely to be borne by the most disadvantaged. While well-functioning anti-corruption hotlines and visible sacking of public employees may be useful to tackle the petty extortion which ‘victimises’ ordinary people, collusive corruption, where all parties benefit, on the other hand is much more difficult to root out and needs a wider set of reforms. The rapid financial inclusion and deepening resulting from the demonetisation will obviously help in reducing black money but it is just one aspect of a multi-pronged strategy that the government needs to undertake including tax reforms, campaign finance reforms, and speedy enforcement of laws against corruption.

From the anti-corruption movement of Anna Hazare, and the landslide election of the Aam Admi Party in Delhi on the anti-corruption platform, to the popular support of government’s current demonetisation policy, it is apparent that there is a deep yearning among the Indian populace for effective anti-corruption policies. The government should use this opportunity to implement wide ranging reforms to tackle corruption, which has blighted the country.