With Devolution, Greater Manchester has an opportunity to encourage investment and inclusive growth by setting its own policy agenda. Dr Marianne Sensier puts the case for the creation of a regional bank within the new mayor’s policy agenda. A regional bank will provide finance for business and allow people to save their money which in turn will help develop the local community.

- Since the financial crisis of 2008 many regions of the UK have struggled and a large imbalance still exists between London and the South East and the rest of the country.

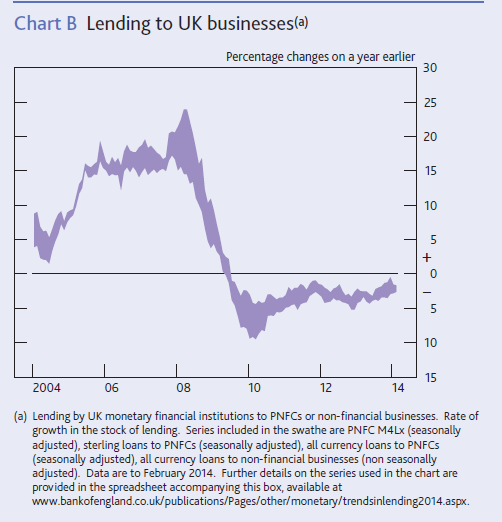

- Bank business lending contracted after the crisis and a recent government report suggests this is still an ongoing concern.

- Could lessons be learned from Germany that has a system of regional banks and actually increased lending to SMEs over the financial crisis?

- A regional bank tasked with a local economic development motive (rather than profit maximisation) could help provide more inclusive growth opportunities to struggling communities.

Only London and the South East have returned to pre-crisis levels of income per head as highlighted in a speech by the Chief Economist of the Bank of England, Andrew Haldane. He also maps the stark regional differences in productivity, weekly pay, wealth, skills levels, unemployment and mortality rates. The regional imbalances become more extreme when comparing smaller areas than Government Office Regions. The Office for National Statistics estimates that the Gross Value Added[i] (GVA) figure per head of population in 2015 ranged from £292,855 in Camden and the City of London down to £13,411 in the Isle of Anglesey, Wales.

In Greater Manchester GVA per head in 2015 was £32,114 for Manchester and £15,778 for Greater Manchester North West (this includes Bolton and Wigan). Could these imbalances be addressed by introducing regional banks as an alternative to commercial banks with the goal of serving the local community and not maximising profit for shareholders? Regional banks could take savings deposits and invest these in local businesses that will create local jobs. This circular flow of money around the local community effectively cuts out the globalised commercial banking sector.

This local finance sector would be fairer and more stable providing the core pillar for creating more sustainable local economic growth where businesses sign up to fair working conditions paying the living wage. Investment should be encouraged in low carbon businesses and economic activity that contributes to community well-being and inclusive growth.

Is British banking fit for purpose?

The crisis that hit the stock markets in 2008 followed a long boom in the UK between 1992 to 2007. The extent of the toxic debt problems that commercial banks were exposed to became clear in 2007 when the US housing market went into downturn (see Stiglitz). In the UK in September 2007 there was a bank run on Northern Rock which had borrowed large sums of money on the international markets to fund mortgages for customers and the British Government stepped in with a loan (a full time-line for the financial crisis can be found here). In February 2008 the British Government nationalised Northern Rock and by October 2008 had bailed out the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds TSB, and HBOS. The British banking sector received about £100bn of UK taxpayer’s money as the banks were seen as “too big to fail”.

The financial crisis had an immediate impact on the real economy with business closures, job losses, reduced working hours and pay freezes throughout 2008 and 2009 (The Guardian’s recession timeline can be found here). Real Gross Domestic Product fell by 6% between 2008 (quarter 2) to 2009 (q2) and took 22 quarters to recover to its pre-recession peak value in 2013 (q3) (Sensier and Artis, 2016). Employment fell by 2.4% between 2008 (q3) to 2010 (q1) taking 17 quarters to recover by 2012 (q3). Unemployment grew from pre-recession peak of 5.2% in 2008 (q1) to 8.4% in 2011 (q4) (when 2.684 million people were unemployed) before returning to 5.1% in 2015 (q4), taking 9 years to recover.

As the commercial banking sector struggled to cope with the aftermath of the financial crisis lending to business in the UK suffered as the Bank of England have highlighted in its publication “Trends in Lending” in April 2014:

A report by the then-Business, Innovation and Skills Dept (BIS) on SME lending and competition highlights the difficulty faced by firms in the UK. There is a high level of concentration in the banking market where 90% of business loans are provided by four banks (Lloyds bank, RBS group, Barclays and HSBC). There are significant barriers to entry for new banks entering this market so an oligopoly market exists and low levels of SME customer satisfaction are reported but few SME switch banks as few alternatives exist.

A study in success: regional banking in Germany

The system of regional banking in Germany is called Sparkassen (Civitas Newsletter). During the financial crisis the commercial banking sector was also cutting back lending to businesses in Germany but the regional banking sector actually increased lending to small business. These banks hold a third of all banks assets in Germany, take 40% of all customer deposits and they provide 40% of business loans and 56% to business start-ups. They are restricted to operate within their local area taking local savings deposits and providing loans to small businesses. The objective of the regional bank is local economic development and they provide “patient” longer term capital which may be seen as higher risk to commercial banks whose objective is profit maximisation.

A recent academic study builds a theory of a financially integrated banking market where rich regions are more attractive to external investments because they have higher initial endowments than poor regions that have fewer projects that need financing. Capital flows from poor to rich regions. In their model an expansion in investment to poor regions with lower levels of economic activity will have a greater effect on productivity than in the rich regions. They empirically test their theory on the German banking sector and find that small bank development improves local economic growth and the effect is stronger in less developed regions.

As we head towards a post-Brexit world European Regional Development funds could be used to capitalise regional banks for the Government Office regions in the UK. These would offer local business loans at reasonable interest rates, in some cases offering lending over a longer term than commercial banks. The businesses that would be offered loans would have to demonstrate in a financial business plan that they will create employment opportunities within the region at the living wage as a minimum. These new institutions would then also take savings deposits from people within the region. As an example of how much money could be saved, if we take the estimate of the number of households in Greater Manchester of 1.17 million (via New Economy) and we then assume that half of these households each invested £5,000 in savings deposits that would further capitalise the regional bank with just over £2.9 billion.

Examples of UK local banks

When the TSB was privatised in the 1980s the Airdrie Savings Bank stayed outside the TSB group and has eight branches and 60,000 customers in Scotland. 80% of its loans go to local businesses and 35% are for five years or more. Good local knowledge has kept losses down so that only 1.7 per cent of total lending was written off in 2010. The Burnley Savings and Loan (or Bank of Dave) began in 2011 and the problems encountered by the owner, Dave Fishwick, for getting a banking licence from the City banking establishment were the subject of a Channel 4 documentary. A Hampshire Community Bank will begin operation soon and is the plan of Prof David Werner from the University of Southampton again along the similar lines of the German savings banks. There is now a Community Savings Bank Association that exists in partnership with the Airdrie Savings Bank which aims to support the establishment of more community banks.

Achieving inclusive growth through governance

The Governance structures of the regional bank would have a management board that has representatives from different parts of society and could include the local authority, Chamber of Commerce, citizen groups and trade unions. Bank employees would then receive modest salaries with no additional bonuses. The bank could also run in partnership with business services offered in the region (in the case of Manchester this would be the GM Business Growth Hub) so businesses are offered guidance and training and have access to the relevant networks to help enhance the regional skills base.

The Government/Bank of England should support the creation of system of regional banks for the public to save into and to provide loans to local business. Decentralising the finance system will help to tackle the extreme regional imbalances that exist within the UK. A local bank could be introduced in Greater Manchester with devolution and the introduction of the Metro Mayor from May 2017.

UPDATE: Marianne’s full policy paper on regional banking has now been published by the Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit. You can read it here (.pdf)

[i] GVA is the value generated by any unit engaged in the production of goods and services in a region (see ONS).