Now that the shock of the Brexit vote has diminished, what next for our economy, trade and the social and regional divisions that the referendum revealed? Diane Coyle says it’s time to redress the massive imbalance between London and the rest of the country and create a multi-engine economy.

Claim and counter-claim

It has not been surprising, perhaps, although it is certainly dispiriting to see so many people concluding that the Brexit vote will or will not harm the economy on the basis of just two months’ worth of economic statistics. There will be a lot of claim and counter-claim to come. But it will be some years before the impact starts to be clear, not least because it depends on the trade arrangements the UK government has yet to even begin to negotiate. Meanwhile, the biggest effects are the more than 10% decline in the pound, a substantial loss of UK purchasing power even though it makes British exports cheaper; and the shadow of uncertainty affecting long-lasting decisions such as research funding and investment.

The long-term economic effects will be negative, however. This is not controversial among economists; it is a statement of logic. Any adverse change in the terms on which we can trade with large, nearby markets can only damage the ability of British firms to export to them, and disrupt the international supply chains in which British exporters participate. It is not tariffs that matter so much as the access to markets on the same terms and conditions as competitors. Hence the City of London’s great concern about banks needing to keep their ‘passport’ to operate in the rest of the EU.

A ‘them and us’ approach

The reality of needing to negotiate favourable conditions, and the risk to London – epicentre of the UK’s high value services such as finance – of getting it wrong, is beginning to dawn on politicians and commentators. For example, journalist Simon Jenkins wrote recently: “London was given a slap across the face by a resentful provincial Britain. …. But Britain needs London more than London needs Britain. So let’s talk deals.”

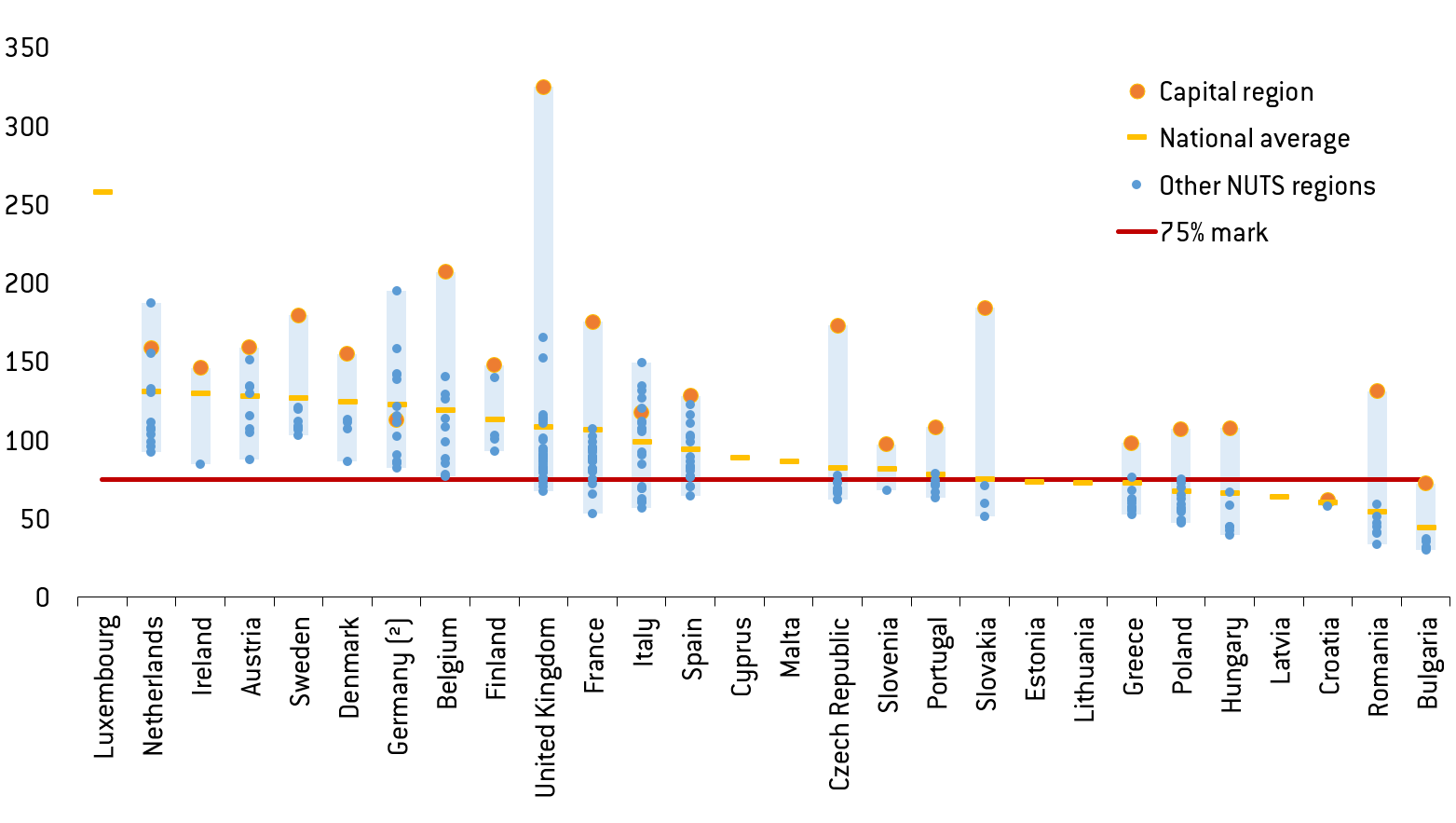

However, this approach embodies a damaging ‘them and us’ approach to the economy. The single biggest structural flaw in the UK is the massive imbalance between London and the rest of the country. The ‘resentful provincials’ are right in the sense that the regional inequality in this country far exceeds the normal variation, as the chart below illustrates.

But the usual metaphor of ‘rebalancing’ the economy, or warning that London must not be damaged, is harmful. No rational person wants to see London’s economic prospects worsened. Yet every rational person should want to see the British economy flying on more than one engine. Powering up the regional engines, such as Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham, and Leeds, is vital. It is politically important, as the geography of the referendum vote suggests, and it is vital if the economy is to overcome the long-term damage caused by the future disruption to trade and investment. A multi-engine economy will be a more productive economy.

- Source: Eurostat. The length of each bar shows how much higher income per capita is in the capital city (orange dot) than the national average (yellow bar) and than 75% of the EU average (red line).

Policy levers for change

Fortunately, there are policy levers that can help achieve this. Government investment in infrastructure, in scientific hubs and in education, has for decades been massively tilted toward London and the South East. This can change easily, even though the effects of such investments take a long time to be felt. With borrowing costs so low, this need not either be to the detriment of London or the Government’s finances.

There is also a wonderful symbolic opportunity right now for the government to signal its intention to support the economy and address some of the factors that drove the Brexit vote. Parliament has just been told it must vacate the Palace of Westminster for six years to allow urgent repairs.

There could be no better signal of a constructive government approach to the substantial economic changes ahead than moving ‘Westminster’ to Manchester or Birmingham for the duration.