Our land is under pressure like never before and post-Brexit, the UK is at a crossroads in land use and environmental policy. Balancing the trade-offs between land use for biodiversity, food production, health and wellbeing and carbon storage to address climate change, will not be easy. Ada Wossink explains how a better understanding of these trade-offs can deliver fairer and more effective land-use policies, making the most of what we have, without trashing the planet.

Agricultural land is under pressure as never before. Increasing concerns about food security, driven by the need to feed a growing population, need to be balanced by conservation of the environment and maintenance of the ecosystem services it provides.

I’m conscious that these pressures pose significant agricultural and environmental policy questions. For me, the key issue is how biodiversity, food production, and other ecosystem services jointly respond to changes in land use and how this varies geographically. Understanding these trade-offs and synergies has become increasingly important for local, national and global policy makers.

Mapping does not help

One conventional way of approaching this problem is by using mapping studies, to provide a kind of inventory of the availability of specific ecosystem services for entire regions or larger areas. In the past, some studies have even combined these mapping exercises with attempts to assess the global value of ecosystem services.

But in my opinion this system isn’t the answer. This is because mapping studies are not linked to changes in land use. If you measuring the total value of ecosystem services it can help to raise awareness, but does little to help a decision maker trying to assess the future consequences of alternative actions in term of land use.

Trade-offs do help

A more effective solution would be to consider the trade-offs. Increasing biodiversity requires a change in land-use that can reduce other ecosystem services such as food. The same reasoning applies to carbon storage in soils and forests to address climate change. Thus the growing concerns about food security, declining biodiversity and reduced carbon storage capacities call for localized insights in the trade-offs of land use changes.

The issue is that if policymakers examine the cost of biodiversity or carbon storage this is often understood in terms of what needs to be given up. Benefits of ecosystem services (such as carbon storage) accrue at the regional and global scale whereas costs (such as giving up food production) are often felt by the local population. Given the concerns about food security, biodiversity and carbon storage, there is an increasing demand for economic information of this kind for regions, countries and areas that overlap multiple countries.

Synergies

In my interdisciplinary research I have been part of a team that developed an approach to estimate the links between a range of ecosystem services and agricultural production taking into account the local conditions. An important first finding was that these connections were not always negative, an assumption often made in economic studies.

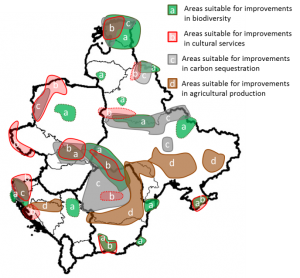

When we apply this method to Eastern Europe, these positive synergies were important. For example, we found that changes enabling more carbon storage were cheaper in areas already having relative high levels of it. More biodiversity was generally costly initially but decreased after reaching a turning point.

Differences between regions

Overall we also found that the costs varied a lot between regions. Generally, landscapes with less productive agriculture have a cost advantage for the delivery of more biodiversity, cultural services or carbon sequestration. For biodiversity and cultural services (such as tourism, recreation and hunting/gathering activities), combining these together as bundles of ecosystem services would be preferable in most areas. But if biodiversity levels are really high, focusing on biodiversity conservation alone becomes cost-effective. Finally, for carbon storage, specialization always is cost-effective. This emphasizes the conflict between local costs such as foregone food production and global benefits (climate change mitigation).

These insights are helpful for making new land-use policy interventions effective and fair. Policymakers need to understand and have easy access to trade-off information specific to their region and find the right mixture of uses for the land.

These insights are helpful for making new land-use policy interventions effective and fair. Policymakers need to understand and have easy access to trade-off information specific to their region and find the right mixture of uses for the land.

Often, there is a negative trade-off, but on the flip-side there are also positive opportunities. An appreciation of these will help get the best out of land that is coming under increasing pressure.