Radioactive waste is a controversial topic. But understanding the difference between historic and new wastes would produce a more informed debate, explains Hollie Ashworth.

Whenever there is talk about new-build nuclear power stations, there is also talk about the cost of cleaning-up radioactive waste.

People often correctly quote figures for the cost of cleaning-up radioactive waste in the hundreds of billions of pounds, but fail to make the distinction between legacy waste and new build waste. Legacy waste can be defined as the radioactive waste produced during the infancy of the UK civil nuclear industry’s development, at a time when, unfortunately, waste storage and treatment was not well planned.

Currently, Government is making greater efforts to ensure that this legacy is no longer left for subsequent generations. Because of this, there is now a large amount of time and money devoted to cleaning-up legacy waste.

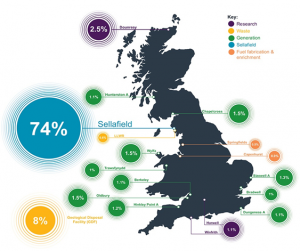

The UK’s Nuclear Provision was set up to deal with the nuclear legacy and forms the best estimate of the cost of cleaning-up the UK’s oldest nuclear sites. The 17 sites this public funding covers can be seen below (source: NDA).

The second generation fleet commissioned in the 70s and 80s (operated by EDF, formerly British Energy) have separate funds set aside by EDF towards their future waste management and decommissioning programmes. This is called the Nuclear Liabilities Fund.

The next generation of nuclear power stations, and all proposed new build in the UK, will be built by the private sector with waste management and decommissioning plans in place from the beginning. This will include cost forecasts for the plans and a Funded Decommissioning Programme must be submitted before construction can start. This may not be completely fool proof though, as forecasts can quickly change.

Many lessons have been learnt from the history of radioactive waste management and decommissioning in the UK. This has meant that the industry has developed a vast amount of expertise with great export potential to both domestic and international markets.

Legacy waste was created as a result of the pressures of war and the world’s first civil nuclear reactor, at a time when waste and decommissioning were not considered. This would simply not be allowed to happen now. The legacy is a priority for Government to deal with as quickly and safely as possible, but it has already presented many unforeseen challenges, with clean-up timescales still estimated at another hundred and twenty years.

The challenge of legacy waste clean-up at a site like Sellafield is two-fold: keeping workers and the environment safe from the radiological hazards, coupled with the engineering challenges of decommissioning such hazardous material within such a compact site. The site is approximately two and a half square kilometres, with more than a thousand buildings including old reactors, waste storage facilities and waste processing capabilities. This site was not planned, but was developed as the requirements of the site changed. Fortunately sites would not be allowed to develop in such a way anymore due to strict planning and regulatory rules. Sellafield has been a world leader in reprocessing spent nuclear fuel and developing innovative ideas to manage and decommission nuclear waste facilities on site, but it still has a very long way to go.

One of the main concerns the public has with nuclear investment is that it will significantly increase the UK’s nuclear waste inventory, causing the cost of dealing with it to increase astronomically.

In fact, the UK’s new build plans would only increase the waste inventory by approximately 10%, by which time we should have a final disposal solution in the form of one or more Geological Disposal Facilities (GDF). However, this is by no means infallible; it would not accommodate the entirety of the UK inventory, and siting one of these facilities is subject to a voluntarist process to find a host community. This process will begin in 2017, and its success is dependent on a number of complex issues which include how to define a potential host community, and how that community will be represented. The expected timeline for its delivery and eventual closure also exceeds one hundred years; so waste disposal is definitely not a short-term task.

The cost of legacy waste clean up is astonishing, but it should not necessarily condemn the future progress of the nuclear industry or dominate all sides of the argument, including the other negatives. The challenges that legacy waste present now will not be recreated in the future, but the issue of radioactive waste will continue to be tricky.