New research drawing on European survey data finds that religious decline does not equal moral decline. Dr Ingrid Storm explains why involvement in religion makes most difference to morality in the most religious countries, and matters less for moral values now than it did in the 1980s.

A recent report by the Commission on Religion and Belief in Public Life called for reforms to religious education and worship in British schools, on the grounds that the current system does not reflect the increasing secularity and religious diversity of British society. Proponents of religious worship in schools (see for example The Telegraph) argue that religious worship can further children’s moral development, teaching values of tolerance and respect.

It is not only Britain where religion plays a smaller part in education and upbringing than it used to. Religion has been in sharp decline in many European countries, and we cannot be sure of the consequences for moral values. With each new generation less religious than the one before, is there any reason to expect moral decline? In a study recently published in Politics and Religion, I analysed data from the European Values Study, and found that religion is related to moral values, but mainly some moral values, in religious countries and when people do not trust the state.

The respondents to questionnaires in 48 European countries over the period from 1981 to 2008 were asked how often they would justify various contentious behaviours, which we can classify into two moral dimensions:

The first, “personal autonomy values”, are about valuing the freedom of the individual to go against tradition, and include justifying abortion and homosexuality. The second, “self-interest values”, are about justifying behaviours that are against the law and could harm others, such as lying, cheating and stealing.

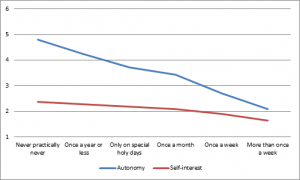

More Europeans are willing to justify autonomy values than justify self-interest values, but the autonomy dimension is also where religion makes the most difference. Religious people score on average lower on “autonomy” than nonreligious people, even considering their age, gender, education, and what country they are from. Religious beliefs and practice make very little difference to self-interest (see Figure 1 below).

As religion declined in Europe there has also been an increase in acceptance of personal autonomy on issues concerning sexuality and family. Each generation is more liberal on these issues than the one before. In contrast, we find no evidence that moral values have become more self-interested or anti-social.

Religious people are slightly less self-interested on average, but this can largely be accounted for by their age. The average religious person is older than the average nonreligious person, and older people, whenever they were born, are less likely to justify self-interest values.

Figure 1: Justifying autonomy and self-interest, by religious service attendance

EVS 1981-2010. (Moral value dimensions measured on 1-10 scale)

In most of Europe there is not much difference between religious and nonreligious people in their attitudes to self-interested behaviours like cheating, lying and stealing. But there is an important exception: among people who have low confidence in state authorities, such as the police, the court and the government, religious people score significantly lower on self-interest than nonreligious people. Previous research has found that religion is strongly related to economic development and it has been argued that this is because religion is a response to insecurity (See for example Norris and Inglehart 2012). This research suggests another possibility, namely that religious norms and networks fulfil a social “policing” function in the absence of credible or legitimate alternatives.

Religious faith and worship also makes most difference to morality in the most religious countries. To be effective, religious norms need to be validated by a moral community of other religious friends and family and social and political institutions. There is also evidence of a change in the relationship since the 1980s: religion has become less associated with for moral values over time, as societies have become less religious.

It is important to point out that the survey only asked questions about “justifying” acts, and did not measure actual behaviour. That said, the research suggests that religious decline is associated with a general shift towards valuing individual autonomy over traditions, but that this is not the same as selfishness or anti-social attitudes. In other words religious decline does not equal moral decline.

This analysis gives us no reason to believe that religious worship makes much difference to moral values in a secular and diverse society. Trust in government institutions appears to be a more important predictor of respect for the norms of society and the autonomy of other individuals. It is mainly when confidence in these institutions is low, that religious beliefs and behaviours, validated by the social environment, can emerge as an alternative source of moral authority and influence attitudes to lying, cheating and stealing.