The key to reducing dementia and sensory loss in later years may lie in improving experiences in the earliest years, explains Piers Dawes.

Dementia, hearing impairment and vision loss are amongst the most feared, most costly and difficult to treat problems in elderly people. One way of avoiding cognitive and sensory impairment in old age may involve increasing attention to the earliest experiences of life.

Sensory impairments are extremely common; one in three people over 65 years suffer sight loss, while seven in ten people over 70 years suffer hearing loss. Over the age of 80 years, one in six people suffers dementia. Besides having a substantial impact on the quality of life of sufferers and their families, treatment of cognitive and sensory impairments is expensive. Cognitive impairments and sensory impairments are in the top ten most costly chronic conditions in western countries.

It is now well established that pre-natal development affects susceptibility to disease including diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adulthood. A small amount of research has also hinted that pre-natal development may affect cognitive and sensory function in childhood and perhaps in adulthood too.

Our research tested whether pre-natal and early childhood development was linked to cognitive and sensory function in adulthood. We used the very large UK Biobank data set with information on up to 500,000 UK adults. This enabled us to detect the effects of early development and control for potential confounding factors, such as age, smoking, socio-economic status, chronic diseases and educational level.

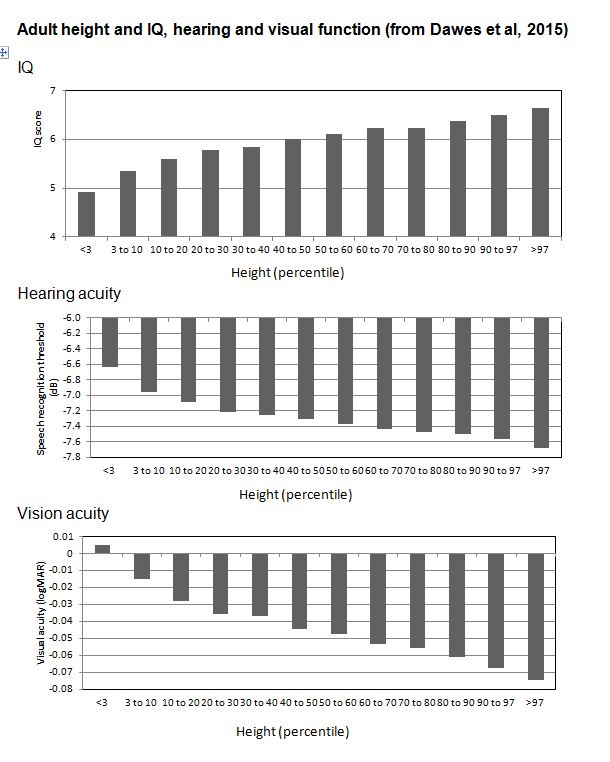

We found that pre-natal development was linked to adult cognitive and sensory function. Both very small and very large babies tended to have poorer cognition and sensory function in adulthood. But within the normal range of birth weight (defined by birth weight between the 10th and 90th percentile), larger babies tended to do better. Similarly, taller adults had better cognition and sensory function (Figure 1).

Birth weight is an index of pre-natal development, while adult height relates to development during early childhood. Early life factors accounted for between 5% and 14% of individual differences in cognitive and sensory function, after accounting for confounding factors. Our research indicated that pre-natal and early childhood developmental factors such as nutrition, illness and maternal health have a critical impact on neurosensory development.

The possible causal mechanisms are i) under-nutrition may directly affect the development of the brain and sensory organs, ii) the pre-natal environment may cause changes in gene expression that affect cognitive and sensory function, or iii) growth factors or maternal stress hormones are modulated by early experience and impact on cognitive and sensory development.

Our research has major implications for understanding the causes and prevention of cognitive impairment/dementia and hearing and vision impairment. Adverse early pre-natal and childhood development would cause earlier onset of dementia, hearing and vision impairment in adulthood.

But early development also provides a powerful opportunity for prevention of dementia and sensory impairment. Interventions in adulthood are relatively ineffective at reversing dementia and sensory impairment. For example, treatments for dementia currently focus on slowing cognitive decline and managing symptoms. The primary treatment for hearing impairment is provision of a hearing aid, but hearing aids do not restore normal hearing. By contrast, early intervention during a much more developmentally plastic period of life could have a significant impact in reducing the numbers of people who go on to develop dementia and sensory impairment later in life.

Early development has already been identified as a research priority in relation to dementia, diabetes and cardiovascular health by EU and US national research bodies. Early development should also be a priority in relation to preventing hearing and vision impairment.

If we want to reduce the number of people with dementia and sensory impairment, government policy should implement research-based interventions that optimise foetal and childhood development with respect to neurosensory outcomes in adulthood. The solution to better adult health and quality of later life may lie in the earliest experiences of childhood.