The day after George Osborne’s Comprehensive Spending Review, Diane Coyle picks out the winners and losers.

One of the most important attributes a Chancellor of the Exchequer can have is to be lucky. Lucky, that is, in all the aspects of the economy that are outside the control of the government – which is most of them. This is all the more important for George Osborne as he had given himself very little room for manoeuvre in his Autumn Statement and spending review. Between his commitment to cutting the budget deficit and government debt ratio, and the fact that a large share of spending – policing, health, education, international aid and defence – had been ring-fenced, Mr Osborne had little choice but to announce large spending cuts in other areas.

There are indeed some large cuts. Capital investment for transport projects – including electrification of the Trans-Pennine rail line – is to go up, but the transport department’s budget is one of the biggest losers; and there are expenditure cuts for energy, business and the environment too. Local councils face a five-year freeze in cash terms, and there are plenty of smaller measures that will be painful, such as replacing grants for trainee nurses by loans and limiting the childcare subsidies for 3 and 4 year olds. Shrinking the size of government as much as Mr Osborne intends (to 36.5% of national output in 2020, from 45% in 2010) is not a trivial matter. It is a serious reshaping of the relationship between government and citizens.

Even so, the extent of the squeeze he just announced was not as bad as expected, or feared. There are some tax increases, notably an ‘apprenticeship levy’ on businesses of 0.5% of their wage bill (when this is greater than £3 million), which will eventually raise £3bn annually to fund apprenticeship places. But the main reason is that the forecast for tax revenues has been increased, and for debt interest payments decreased.

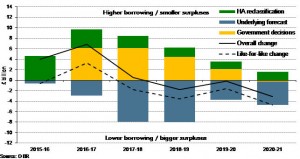

The chart below, from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), shows just how much the changes in the economic forecast have helped the fiscal arithmetic (the blue bars, reducing the borrowing forecast). This has permitted the increases in borrowing due to government policies (yellow) and the fact that housing associations are now being counted in the public sector because of the government intervention to allow the tenants the right to buy (green) – without breaking the Chancellor’s self-imposed fiscal rules.

His luck is our luck too. The trouble is that economic forecasts change frequently. The global economic environment is concerning. Financial markets could fall sharply. The OBR is an independent body doing its best to provide objective and reasonable economic forecasts. But if it downgrades its forecasts at some stage in the future, further spending cuts will be on the agenda again.