When Francis Fukuyama published his now famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) initial essay on “The End of History” in 1989 it provoked a furious discussion that continues to this day (the later book version is here) and is continued here by Colin Talbot.

The discussion has often generated more heat than light, with some of his critics reading things into what he said that just weren’t there. That is perhaps understandable, as he posed fairly fundamental questions about where human society and history is going.

Fukuyama’s mistake (if it was such) was to label the end state of history as the ‘Liberal Democratic’ state. This has been widely taken to mean some version of USA style ‘liberal democracy’ with a relatively small public sector, as opposed to the conservative or social democratic states of Europe with rather larger and more interventionist states. A great deal of energy has been expended proving that there are actually ‘diverse’ (or even divergent) forms of capitalism and welfare states.

What Fukuyama actually said was that ‘liberal democracy’ included two elements – political and economic liberalism and democracy. The first means the respecting of individual rights to property, contract, free speech, religious observance, etc. Democracy overlaps with some aspects of liberalism, so defined, but includes the right to vote, to organize political parties, to elect and reject governments, etc.

He makes it quite clear that this definition includes countries “ranging from the United States of Ronald Reagan and the Britain of Margaret Thatcher to the social democracies of Scandinavia and the relatively statist regimes in Mexico and India.” (The End of History and the Last Man, p44)

Fukuyama was arguing primarily that the other two great experiments of the 20th century – fascism and communism and their slightly weaker imitators – had been gradually replaced by his (rather widely defined) liberal democratic states.

These liberal democratic states included a substantial publicly provided welfare regimes (of different types) and this was also historically very different.

In 1910 the proportion of national wealth allocated to government provided public action was about 10% of GDP (or its equivalent) in most of the countries that make up what is now the OECD block.

By 2010 that had risen to somewhere slightly north of a 40% average of GDP for these countries – creating a historically much larger ‘state’ in all these countries. Of course there was quite a lot of variation – from what are more commonly called ‘liberal democratic’ states like the USA (around a third of GDP) to the social democratic Scandinavian states (usually more like half or more of GDP).

This means that there are really three elements involved here – democracy, a substantial state and substantive liberties especially in the form of private property and markets. I will call this the “Democratic State Market” which I think captures the essence of this historic phenomena better, and with less unnecessary connotations, than the term ‘liberal democracy’.

Varieties of democratic state market

There have been three parallel but surprisingly disconnected debates in academia about variations and typologies between Democratic State Markets (DSMs):

- in political-economy with the seminal ‘Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage’ (Hall & Soskice, 2001);

- in welfare state studies the widely cited ‘The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism’ (Esping-Andersen, 1989, )

- and in political science the classic ‘Patterns of Democracy’ (Lijphart, 1999, 2012)

In a sense these three discussions address the three aspects of Democracy (Lijphart), State (Esping-Andersen) and Markets (Hall & Soskice). What is surprising is how little interaction there has been between these three areas of exploration. (It is also very noticeable how much these three discussions have mushroomed since the fall of the Communism in Europe, as well as since Fukuyama’s original article.)

One recent and very welcome exception to the splendid isolated silos of these three discussions is a recent book by Martin Schröder ‘Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research’ (2013) which finally attempts to bring two of them together (rather well I think).

Schröder’s argument is, simply put, that it is quite possible to integrate the two-way typology of ‘varieties of capitalism’ (which focuses on the firm and ‘production’) and the ‘three worlds of welfare capitalism’ (which focuses on the state and ‘consumption’) to create a single unified typology. This creates three configurations of ‘capitalism’: the ‘liberal’, ‘conservative’, and ‘social democratic’.

Schröder includes in the ‘liberal camp the USA, UK, Ireland, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. The ‘conservative’ countries are Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Japan. The social democracies are Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway.

I am not, at this point, going to discuss either the methods by which Schröder comes to these categories or categorizations – suffice it to say I think this would all benefit from a dose of ‘fuzzy set theory’ to make the analysis both more rigorous and realistic. For example I would contend the UK lies very much on the ‘fuzzy border’ between the set of liberal democratic and social democratic countries, with elements of both present.

But if we take the size of ‘general government spending’ as a proportion of GDP as a rough guide to the balance between ‘state’ and ‘market’ in each country then this group of advanced countries produces interesting results.

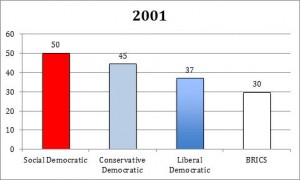

Figure 1: Public Spending as % of GDP by type of regime (plus BRICS) 2001

Source: calculated from OECD figures

There is a pretty clear differentiation between the three groups average public spending. I have added the ‘BRICS’ countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) just as an interesting comparator.

I have used the figures for 2001 – well before the impact of the 2007-8 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and during a period of relatively smooth global economic growth (see Figure 1).

There is a 5-point gap between the social democratic and conservative countries, and further 8-point gap between the latter and liberal states, matching the supposed characteristics of the three types, and 13 points between the top and bottom ‘big governments’. But it is useful to again emphasize, in all of these cases a century or so earlier they would have all been only around 10% of GDP.

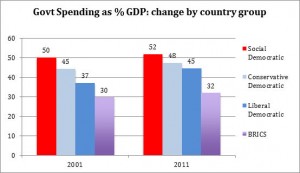

However if we jump forward a decade to 2011 (see Figure 2) the gap between the blocs had narrowed considerably. Between social democratic and conservative it is down to 4 points (-1) and between the latter and liberal states to only 3 points (-5) – giving a spread of only 7 points (-6).

Interestingly the BRICS countries gained slightly (from 30 to 32%) but remain a consistent 7 points behind the liberal democracies.

Figure 2: Public Spending as % of GDP by type of regime (plus BRICS) 2001 & 2011

Source: calculated from OECD figures

Public spending as a percentage of GDP is a very crude indicator. Because it is a ratio to GDP, any short-term fluctuations in the latter (e.g. the GFC) can distort the picture dramatically (e.g. the sudden jump in the UK government deficit as a proportion of GDP was from 3% in 2007 to 11% in 2008, partly because of the fall in GDP). Measuring GDP also has its own problems, as my colleague Diane Coyle and others have pointed out.

So the figures above may be purely suggestive, but they are that. They indicate there may well be something in the ‘varieties of democratic state market’ (although we have yet to connect the third ‘democratic’ leg to the stool)? It may also suggest Fukuyama may not have been so far wrong and maybe even these distinct regimes are starting to converge within the DSMs?

What Schröder’s analysis doesn’t really tell us is if there is a link between the democratic regime – as in Lijphart’s ‘Patterns of Democracy’ for example – and the welfare and political-economy patterns? But that is for another day……