Ethnic minorities are heavily over-represented at all stages of the criminal justice system. We have to look at the wider structure of inequality to understand why, argues Stephanie Wallace.

Two dominant explanations generally account for the over representation of ethnic minority groups in the criminal justice system; ethnic minorities commit more crime and institutionalised racism. The first argument is that ethnic minority people commit more crime and are therefore more likely to end up in the criminal justice system. This position suggests that ‘cultural deficits’ within certain ethnic minority communities are responsible for higher crime rates.

In a recent article in the Sunday Times, Trevor Philips argued that these ‘criminogenic cultures’ need to be understood so that they can be stopped from happening. However, he has received criticism for failing to acknowledge that the disproportionate numbers of ethnic minorities in the criminal justice system may be borne out of institutional racism at all stages.

Therefore an alternative explanation for the over-representation of ethnic minority people in the criminal justice system is that the system is institutionally racist. Many argue that various practices, policies, procedures and operations within the criminal justice system reinforce racial prejudice. Over policing and the use of stop and searches is often cited as just one example of institutionalised racism, in which Black and Asian men are far more likely to be stopped and searched and arrested compared to White men.

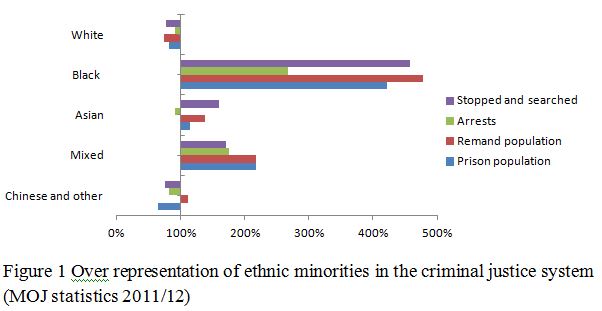

In England and Wales, ethnic minorities are over represented at all stages of the criminal justice system compared with their representation in the population aged over 10 years – the age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales. Figure 1 shows the relative rates of representation at different stages of the criminal justice system compared to the representation in the population for each ethnic group. The axis, 100%, would be the level at which the rate was proportionate to population size, above that indicates a higher risk, below that a lower risk. The figure indicates the substantially greater risk for those in the Black group, with a higher risk also present for those in the Asian and Mixed groups.

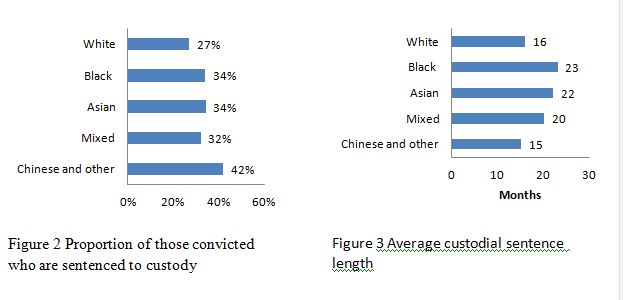

As another example, Figure 2 shows the proportion of those found guilty of an indictable offence and who are then sentenced to custody. Figure 3 shows the average custodial length of those sentenced for an indictable offence. In each case ethnic minority offenders receive harsher treatment than White offenders, with the exception of duration and those in the Chinese and other group, who have a similar length to those in the White group.

However, we must treat these figures with caution. Firstly, government statistics do not take into account the type of offence the offender was sentenced for. Secondly, they do not take into consideration the culpability and harm caused by the offender, which affects the seriousness of the offence. Additionally, they do not account for prior convictions which are treated as cumulative aggravating factors; or the offence plea. Such factors increase the severity of the offence, which ultimately affects whether an offender receives a custodial sentence, as well as the length of the custodial sentence.

Research has shown that ethnic minority offenders are more likely to plead not guilty compared to White offenders. This has implications for the sentencing figures and could offer some explanation for their over-representation in the prison population. It means that if found guilty, the offender will not benefit from the discount awarded to those offenders who plead guilty at the earliest possible opportunity (33% reduction in sentence); plead guilty during police questioning (25% reduction in sentence); or plead guilty on the day of their trial (10% reduction in sentence). As a result of this, ethnic minority offenders are also more likely to face a jury verdict in the Crown Court and if found guilty are more likely to receive a severe sentence.

Indeed, even prior to sentencing, ethnic minority people are over-represented in the proportion of those arrested and those who were stopped and searched under Section One of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 – far more than their representation in the population.

A third explanation considers the effects of deprivation and inequality, and suggests that to understand the over-representation of ethnic minorities in the criminal justice system we also need to consider the broader inequalities in society. This explanation adds nuance to the notion of institutional racism, by showing that we must also consider inequalities in the wider social and economic structures.

To understand the over-representation of ethnic minorities in the criminal justice system we have to look further, at the wider inequalities currently faced by many ethnic minorities. Inequalities in education, employment, and housing tenure – and the fact that ethnic minorities are more likely to live in deprived areas compared to the White population – reinforce the socially disadvantaged positions of many groups.

The compounding inequalities in education, employment and in where you live can make you more likely to come to the attention of the criminal justice system in the first place – for example, being excluded from school, or being unemployed and/or being present in deprived neighbourhoods. Furthermore, research has also highlighted the links between deprivation, being excluded from school and entering into the criminal justice system.

I would argue that rather than trying to understand so-called ‘criminogenic cultures’, we need to focus our attention on addressing the existing inequalities that disproportionately affect ethnic minority groups. Only then can we begin to understand how the myriad of inequalities faced by some ethnic minority groups impact on their representation in the criminal justice system.

- The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).