As official Government figures show that the UK economy deflated in April, for the first time since the 1960’s, Diane Coyle looks at whether we should be worried.

There was much excitement about the news that the UK’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) declined by 0.1% in the 12 months to April. A negative figure for this measure of inflation – the first since 1960 – raised the spectre of deflation.

For one (just about) negative number, however, this was excitement verging on the hysterical. Deflation can be a serious economic problem, and some economists do think we are heading there. It becomes a problem when prices fall for a long enough period to change the way people behave, causing them to put off purchases in the expectation of paying less in future. This can become a vicious circle: prices are falling, demand falls, so businesses cut prices again.

The other adverse feature of deflation is that it increases the real value of debts, which is unwelcome when the level of debt in the economy is still so high. If anything, the UK needs a bout of moderate inflation to whittle away some of the real burden of the debts built up in the boom years.

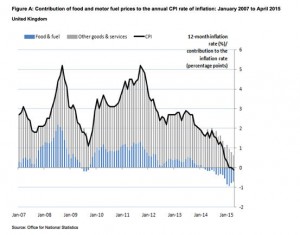

But it is far too soon to expect the worst. The decline in CPI inflation in the early months of 2015 to such low rates is due mainly to the fall in the oil price, working its way into energy and transport costs. The published inflation rate is a year-on-year comparison, and these costs were higher 12 months ago. Other measures, including the Retail Prices Index, are still rising, though at a slower rate than in 2014.

Indeed, every household will face a different inflation rate depending on its spending patterns; the official index is based on a ‘basket’ of goods and services that mirrors average spending patterns. Individual inflation rates can be calculated here. Somebody paying rent in the south east of England and with no car and modest energy bills, but fond of eating out and a keen user of broadband and mobiles will be experiencing higher inflation.

Other indicators (such as retail sales and house prices) suggest that the economy is growing at a reasonable clip. Now that earnings are at last starting to rise, a small decline in prices is actually welcome news because it makes people’s money go further.

The time might come to worry about deflation. If it does, it will be concerning because the Bank of England has little scope to address it with monetary policy, while the size of the government budget deficit limits the scope for fiscal policy to try to inflate the economy. We will need to wait a few more months to know if deflation is a reality, not just a spectre.

Source for data the Office for National Statistics.

Source for data the Office for National Statistics.