Minimum wage legislation is supposed to deliver earnings that protect an individual’s living standard from falling below an acceptable level. Quite often it does no such thing, explains Dr Simon Peters.

Setting the UK national minimum wage should be a key policy in the framework of equality legislation. Yet there are serious doubts about whether the minimum wage is actually sufficient to provide an adequate income. This is particularly important, as the minimum wage has a role in determining the distribution of income between ethnic groups.

The minimum wage is set at a rate that is substantially below the UK’s average pay. For an adult of 21 or older before October of last year, the minimum wage was £6.31 an hour. If this adult was fortunate enough to have a full time job with a standard working week of 37 and a half hours then he or she would have earned a gross weekly wage of about £237.

We can compare this to the UK average wage figures for the UK, as reported by the Office for National Statistics. The provisional figure for 2014 is £518 gross a week. This is a median average which is not affected by a small number of extremely high earning employees such as bankers and professional footballers.

However, these are gross figures and so affected disproportionally by tax and national insurance. This complicates the sums somewhat. To get the net figures, we have to aggregate up the gross weekly pay to its annual equivalent, decide upon a tax year for the calculations and work out the deductions.

This calculation has an added twist as there were different minimum wages for each half of the tax year. For 2014-15, the minimum rose to £6.50 last October. So for the 2014-15 tax year, someone on the minimum wage had average weekly net take home pay of about £220, compared to £409 net for someone on the median wage for 2014.

A common threshold – which is used to calculate the UK’s poverty line – is to take 60% of the median value as a cut-off point. The weekly earnings for someone on the minimum wage is about 54% of the average weekly pay for an individual in the UK. We could consider this as meaning that a person on the minimum wage is in pay poverty.

It is also significant that someone on the minimum wage earns less than the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s minimum income standard for an individual, which is £269 a week net for 2014 according to their calculator. Their methodology is based around the requirements for a “socially acceptable quality of life”, rather than purely net income.

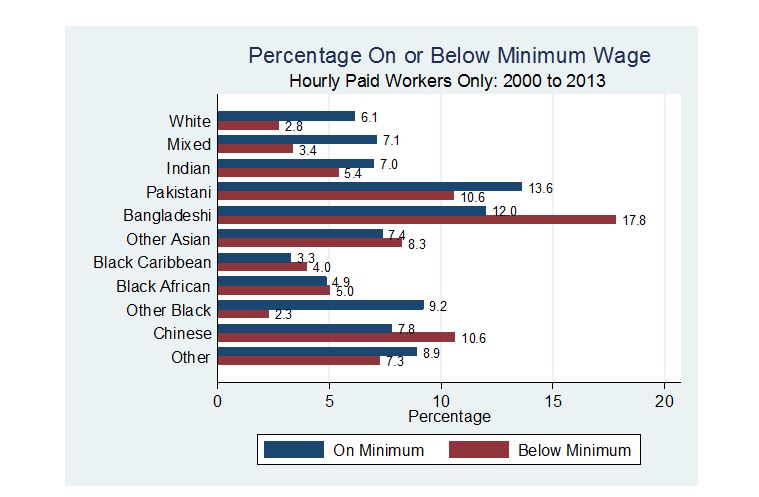

To determine how the minimum wage is distributed amongst ethnic groups in the UK is more complicated, requiring some manipulation of survey data to extract relevant figures. These are presented in the bar chart below and represent the percentage of hourly paid adult workers on or below the national minimum wage rate in each of ten ethnic group categories.

The most striking feature of this chart is the position of the Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic minorities. The total figures for both these groups suggest that, historically, around a quarter or more of these hourly paid workers are on or below the minimum wage rate.

These two groups also fare the worst when we look at being just on the minimum wage (the blue bars) or being below the minimum wage (the red bars). The Pakistani group has the largest percentage of hourly paid workers on the minimum wage, while the Bangladeshi group has the largest percentage earning below the minimum wage rate.

Interestingly, the Chinese group comes equal second of all the groups below the minimum wage. This is an ethnic group that is commonly perceived as being less likely to be poor. However, as this chart illustrates, this perception does not stand-up when those on low pay are taken into account.

It seems that these three ethnic groups are also most prone to non-compliance by their employers to the minimum wage legislation. This could relate to the sectors they work in. Some of the top excuses for non-compliance appear to arise in parts of the catering sector. Meanwhile, both HM Revenue and Customs and the Resolution Foundation have issued reports and warnings of breaches of minimum wage legislation in the social care sector. Pay that is below the legal minimum wage, of course, pushes people even further below the poverty threshold.

It is clear that the minimum wage does not deliver an adequate barrier to poverty. An individual earner on the minimum wage is parked on pay poverty and below a socially acceptable quality of life. Such individuals could be considered to be in working poverty.

There is also inequality present among hourly paid employees, in that certain ethnic minority groups – Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers in particular – are more likely to be on or below the minimum wage. The Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups overall have high poverty levels and for those on low pay, the national minimum wage is maintaining this position rather than alleviating it.

The lack of compliance by employers to paying the national minimum wage has made things worse for nearly all the minority ethnic groups, with the Chinese group now joining the Pakistanis and Bangladeshis as the most affected.

- The views presented here are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of other members of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).